Blog Post

The Italian Lira: the exchange rate and employment in the ERM

In the decades before Italy joined the Euro, the Lira was devalued many times relative to the Deutschmark. Were these re-alignments accompanied by long term improvements on the labour market? The data suggests this was not the case.

In a recent paper, Ferdinando Giugliano and Christian Odendahl argued that the two causes of Italy’s poor economic performance in the past 20 years have been Euro membership and, more importantly, a failure to apply deep reforms.

In its annual evaluations, the European Commission has talked repeatedly about structural weaknesses (see most recent report here) and there is little disagreement on the need for structural reforms.

But the role of euro membership is less clear. Does a flexible exchange rate offer an additional instrument that can bring lasting benefits beyond the immediate impact on the trade balance?

In this blog we ask whether the exchange rate actually helped Italy to achieve sustainable employment gains in the past. We look at the period between the start of the Exchange Rate Mechanism (ERM) in 1979 and the full abandonment of the Lira in 1999.

We observe that exchange rate volatility and depreciations during that period do not appear to have benefited employment in Italy. By contrast, it is in periods of stable exchange rates that the Italian economy moved towards reaching its potential, which also brought benefits in employment.

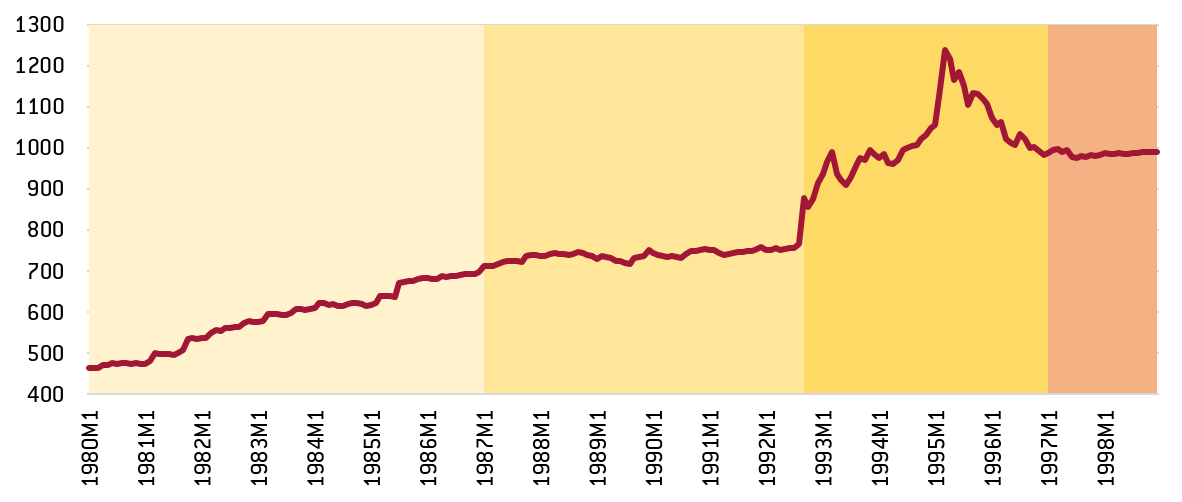

The history of the Lira in the era of ERM was one of multiple devaluations and volatility. Table 1 summarises the size and timing of the Lira’s re-alignments vis-à-vis the Deutschmark (DM) within the ERM. (As the currencies were allowed to fluctuate within bands, these re-alignments were not necessarily the way that actual exchange rates changed.)

In cumulative terms, the Lira lost around half (53%) of its value vis-à-vis the DM by the end of this 20-year period. However, there were not equivalent gains in real terms, since employment levels at the end of this period were very similar to what they were at the start.

In order to summarise the Lira’s exchange rate movements and their impact on the real economy we observe four distinct periods.

Figure 1: The Italian Lira vs the DM.

Source: IMF International Financial Statistics (Monthly frequency)

Notes: An increase denotes depreciation of the Lira. ITL/DM; colours correspond to the 4 periods described in the text.

The first period is 1980 – 1987. This period saw seven exchange rate realignments, which reduced the value of Lira in small steps. At the end of this period, the value of the Lira had fallen by 33%.

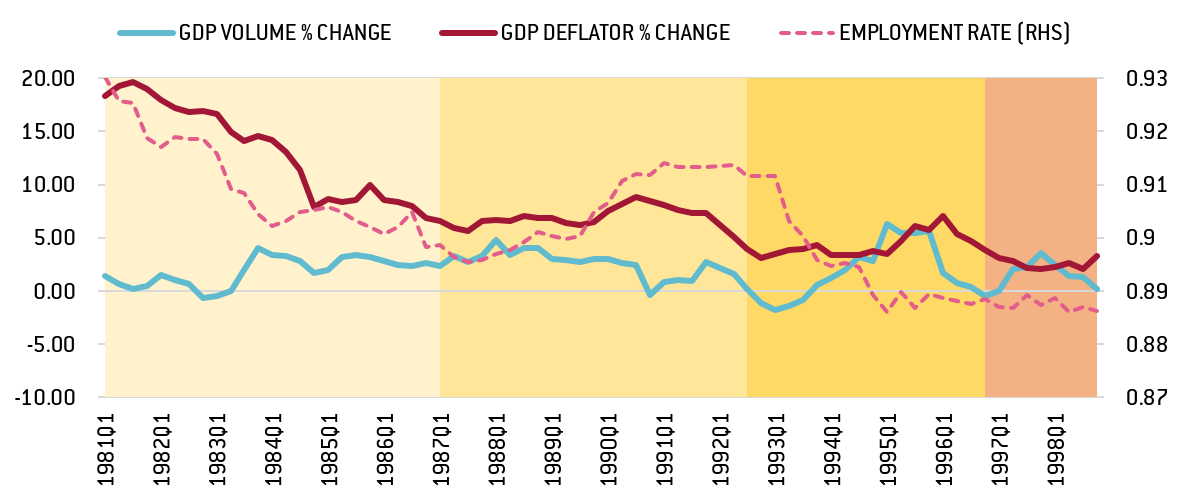

The first four years of this period were ones of stagflation with very high, but rapidly declining, inflation and zero growth. A concerted effort in Italy, not unlike that made in the rest of the world, did reduce inflation. However, there were also with major losses in growth and employment, again not unlike what we saw in the US, for example. Importantly, Italy maintained competitiveness with respect to its trade partners and managed to achieve positive growth and improvements in employment in the second half of this period.

Figure 2: Output and employment growth, Inflation (in GDP terms), Y-o-Y % changes

Source: IMF International Financial Statistics (National Accounts section – Quarterly) and Istat.

In the second period, 1988 – 1992, the exchange rate was stable. There was a small realignment within the ERM in 1990 but not one that had any impact on the actual exchange rate. The end of the period was Italy’s departure from the ERM in September 1992 (although this was not triggered by Italy itself). During this period, inflation had successfully been reduced, growth was positive and there were signs that the economy was operating at its potential. This had led to visible gains in employment.

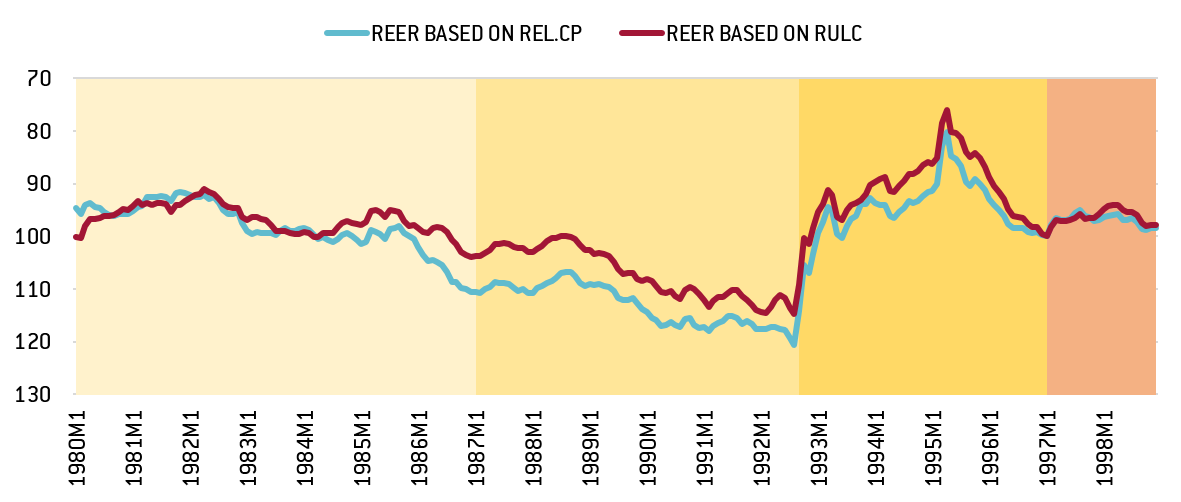

But two pressures were building up, which eventually ended this period of stability. First, Italy was starting to lose competitiveness as its real effective exchange rate (ULC based shown in figure 3) lost more than 10 per cent. At the same time, and following re-unification, inflationary pressures in Germany were leading to increases in the interest rate. Indeed, from the start of 1990 we saw a real divergence in the path of policy interest rates. But as the German policy rate increased there was also pressure for the DM to appreciate. These pressures became unsustainable (in terms of reserves) and the ERM was forced to break in 1992.

Figure 3: Real Effective Exchange Rate

Source: IMF International Financial Statistics (Monthly frequency) – inverted scale.

Notes: *An increase denotes real depreciation.

The split of the ERM in 1992 also marked the start of the third period, a period of volatility and large losses for the Lira. At the starting point, there was agreement on a 3.5 per cent Lira devaluation and 3.5 per cent revaluation for everyone else with respect to the central parity. For the Lira, this amounted to a total of 7 per cent immediate devaluation and an almost 15 per cent effective devaluation within the first month. In a comment to La Stampa Mario Monti commented that this event was “a grave defeat for Italian economic policy.”

Figure 1 shows that the depreciation of the Lira continued for some time. Even though it did recover somewhat, the Lira would not return to the 1992 value before the pre-fixing of exchange rates in 1997, in order to qualify for EMU. Till the end of 1996, the Lira lost 22 per cent with respect to the Deutschmark. This brought big improvements in competitiveness, especially in ULC terms, which translated to an increase in net exports. However, the start of this period saw Italy enter a recession and there was a real reduction in employment. Unemployment rose to levels higher than those prior to the ERM.

The Lira rejoined the ERM at the end of November 1996. Thus our fourth period, beginning in 1997, is the start of transitioning to the European single currency. Stable exchange rates were associated with stable levels of employment. On the first of January 1999, the currencies were locked into their central parities and monetary policy was centralised with the creation of the Euro.

Giugliano and Odendahl do not suggest that exiting the euro is the right way for Italy. But others do. And this discussion is not new. But even if one could ignore the possible political or indeed legal difficulties with pursuing such an option, the gains in the real economy associated with exchange rate movements have been very limited in Italy in the past. By looking at these four distinct periods between the start of ERM and abandoning the currency, we observe that exchange rate volatility and distinct depreciation episodes do not appear to have benefited employment in Italy. This is not to say that depreciations did not help the trade balance. But what they do not appear to have done is to provide sustainable gains in competitiveness that would translate to real and long lasting economic growth.

Technical appendix

Notes on Table 1

Source: Eichengreen, B., & Wyplosz, C. (1993). The Unstable EMS. Brookings Papers on Economic Activity, 51-143. Gros, D., & Thygesen, N. (1998). European Monetary Integration. New York: Addison Wesley Longman. Maes, I., & Quaglia, L. (2003). France’s and Italy’s Policies on European Monetary Integration: a comparison of ‘strong’ and ‘weak’ states. EUI Working Papers, and IMF International Financial Statistics (IFS). Shows % realignment of the bilateral ITL/DM central rate resulting from the different realignments. The last row shows the month-to-month depreciation in the market rate (end August-end September) when Italy left the ERM.

Notes on figure 2

Notes: GDP volume and GDP deflator year-on-year % changes; the employment rate (measured on the right-hand scale) is defined as employment (seasonally adjusted) to labour force (seasonally adjusted). For both series, the age group is >15 years old. Essentially, what is shown is 100% minus the unemployment rate for this age class. For seasonal adjustment, X-12 ARIMA was used.

Notes on figure 3

REL.CP: Relative consumer prices; RULC: Relative unit labour costs. Series are rebased so that 1997M1=100.

REER BASED ON RULC refers to the relative normalized unit labor cost in manufacturing index from the IMF IFS (line reu in the IFS) that was discontinued in March 2010. Output per man-hour is normalized to remove distortions arising from cyclical movements (e.g. labor hoarding) using the Hodrick-Prescott filter. The series was calculated based on a basket of 17 economies.

Republishing and referencing

Bruegel considers itself a public good and takes no institutional standpoint. Anyone is free to republish and/or quote this post without prior consent. Please provide a full reference, clearly stating Bruegel and the relevant author as the source, and include a prominent hyperlink to the original post.