Blog Post

China’s financial liberalisation: interest rate deregulation or currency flexibility first?

Part I discusses three institutional factors favouring a strategy of greater currency flexibility ahead of fuller domestic interest rate liberalisation. Part II (coming later this week) explores three cyclical factors that would tend to favour the same strategy.

Part I discusses three institutional factors favouring a strategy of greater currency flexibility ahead of fuller domestic interest rate liberalisation. Part II (coming later this week) explores three cyclical factors that would tend to favour the same strategy.

PBC is currently negotiating a tricky transition away from a convoluted monetary regime

China’s central bank, the People’s Bank of China (PBC), is currently negotiating a tricky transition away from a convoluted monetary regime that features a managed currency, a controlled capital account and a regulated domestic interest rate. Chinese policymakers have so far pursued a financial liberalisation strategy involving simultaneous and small steps on all three fronts: incremental opening up of the capital account, deregulating most of the domestic interest rates except the official ceilings on benchmark bank deposit rates, and instilling some two-way FX volatility into the renminbi (RMB). The global financial system and economy has a big stake in the fate of Chinese financial liberalisation, which is promising but risky.

But should domestic interest rate liberalisation or currency flexibility lead, in particular in the context of the Chinese communist party’s reform announcements late last year? While there are no black-and-white answers to this question, the current state of the Chinese financial system and the eventual financial reform end game might help identify which strategy is currently preferable.

It would be useful to first put the Chinese monetary system in perspective. Before the “unconventional era”, most OECD economies had a monetary regime characterised by a free floating exchange rate, a benchmark overnight interest rate set by the inflation-targeting central bank, and a yield curve mostly shaped by domestic and global market forces, which would in turn influence bank rates for retail consumers and small firms. Private agents would then respond to such price signals in their decision making. End of the story.

The Chinese monetary system, however, differs from this simple paradigm in at least three important aspects. First, the RMB exchange rate is heavily managed, initially against the US dollar and after 2005 in part with reference to a undisclosed basket of currencies (Ma and McCauley, 2011).

Second, the Chinese government still sets the ceiling on key term benchmark bank deposit rates, but many other interest rates, including bond yields, money market rates and bank lending rates are mostly determined by market forces. So the yield curve is still under heavy government influence in China.

Third, state banks, state-owned enterprises (SOEs) and local governments are still big players on both the demand and supply sides of the Chinese credit market (Ma, 2007). The state banks maintain two thirds of the Chinese deposit market share, and two thirds of Chinese bank loans still go to SOEs and local government investment vehicles.

These important factors may help shape the likely path of China’s financial liberalisation

These important structural and institutional factors may help shape the likely path of China’s financial liberalisation, in three main ways.

First, as SOEs, local governments and their investment vehicles remain big borrowers in the Chinese credit market, but still face “soft budget constraints”, they therefore tend to be less sensitive and less responsive to market interest rates, partially nullifying the potential benefits of allocating capital more efficiently via market-based interest rates. Hence additional economic reforms on other fronts would ideally be needed to support fuller interest rate liberalisation.

Worse, the presence of implicit government guarantees might initially aggravate moral hazard risks in the wake of loan interest rate deregulation, because state banks might take excessive risks, and because of implicit government guarantees to the SOEs, the credit spread of private firms over SOEs demanded by banks and bond investors has actually widened, as interest rates became more market-based (Zhang and Huang, 2014). This perverse outcome would further distort the credit market and punish the private sector, which has been the main source of productivity growth in the Chinese economy.

Thus more needs to be done to wean the SOEs off government support and to strengthen the financial discipline of SOEs, state banks and local government, before market-based interest rates can meaningfully improve the allocation of capital in China.

Second, a functioning deposit insurance scheme should be in place ahead of full interest rate deregulation. Chinese policymakers appear ready to roll out the first ever deposit insurance scheme in China. This is much needed, because price competition among banks is expected to intensify, likely squeezing interest margins and possibly leading to bank failures. However, it might take time for the new deposit insurance scheme to function properly, because banks, depositors, market participants and regulators all need to gain experience and adapt to the new regime.

Third, the PBC may also need more time to ready itself for a new monetary policy regime. With fuller domestic interest rate deregulation, the PBC will have to be responsible for anchoring the short end of a more market-based yield curve. Presumably in this new world, the PBC would also like to shift toward an OECD-like monetary policy regime featuring a policy rate or some benchmark short-term interest rate as its key operating target. At the moment, however, the PBC still targets money supply using a mix of administrative, quantitative and price instruments, such as reserve requirements, open market operations and administered deposit rate (Ma, Yan and Liu, 2011). So it remains to be seen whether the PBC is ready to play its role in a new era of fully liberalised interest rates.

Since 2013, the PBC has been actively introducing more new policy tools such as the short-term liquidity operations (SLO), and considering a wider set of eligible collateral, in addition to its more traditional open market operations. Nevertheless, new tools to help it hit the policy rate target should ideally be tested and refined first.

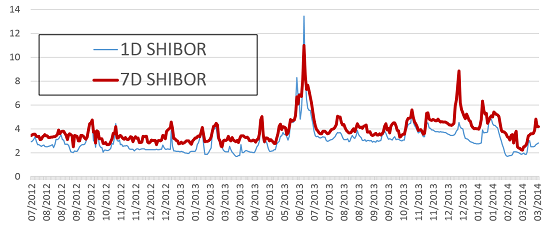

Over the years, the PBC has also painstakingly nurtured local benchmark interbank rates such as the overnight and 7-day SHIBOR (Shanghai Interbank Offered Rate) rates, which form the base for the short end of the yield curve and serve to price off many interest rate derivative contracts and negotiable certificates of deposits.

These benchmark short rates, however, suffered sharp swings in June 2013, raising questions about their usefulness and reliability (Graph 1). While some claim that this “controlled experiment” with the SHIBOR rollercoaster was a warning to misbehaving banks, others are simply baffled why one should abuse these bellwether interbank rates in order to curb shadow banking that often caters to the financing needs of Chinese local governments, which are less interest-rate sensitive in the first place.

Graph 1: Daily Shanghai interbank offered rates (%)

In any case, one may ask whether the recent rising and positive real interest rates in China represent a move to an equilibrium level, or are a reflection of the underlying distortions in the unmistakably weakening Chinese economy. The Chinese economy currently needs a more flexible currency that could help absorb shocks, rather than a more volatile interest rate that could inflict damage on the economy. In another article tomorrow, I will make this same point on the basis of three cyclical considerations. Hence one can argue that for China currently, exchange rate flexibility should go ahead first before fuller interest rate liberalisation. Stay tuned.

***

References

Ma, G (2007): “Who pays China’s bank restructuring bill?”, Asian Economic Papers, 6 (1), pp 46-71, MIT Press.

Ma, G and R McCauley (2011): “The evolving renminbi regime and implications for Asian currency stability”, Journal of the Japanese and International Economies, March, No 25, pp 23-38.

Ma, G, X Yan and X Liu (2012): “China’s reserve requirements: practices, effects and implications”, in China Economic Policy Review, Vol 1, No 2 pp 1-34.

Zhang, Z and H Huang (2014): “Stress testing China’s bond market”, HSBC.

Assistance by Simon Ganem is gratefully acknowledge

Read more on China

China seeking to cash in on Europe’s crises

Review: The China slowdown effect

Financial openness of China and India: Implications for capital account liberalisation

Developing an underlying inflation gauge for China

Are financial conditions in China too lax or too stringent?

How tight is China’s monetary policy?

The Dragon awakes: Is Chinese competition policy a cause for concern?

How loose is China’s monetary policy?

China gingerly taking the capital account liberalisation path

Republishing and referencing

Bruegel considers itself a public good and takes no institutional standpoint. Anyone is free to republish and/or quote this post without prior consent. Please provide a full reference, clearly stating Bruegel and the relevant author as the source, and include a prominent hyperlink to the original post.