Blog Post

The changing fortunes of the Chinese renminbi

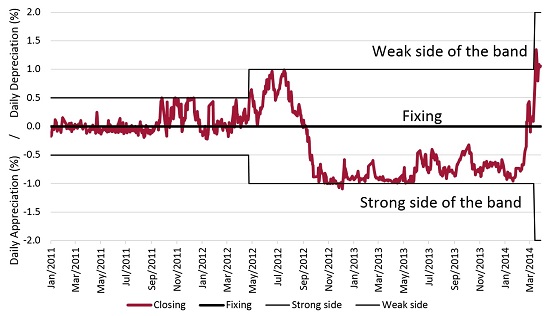

The Chinese renminbi (RMB) depreciated by as much as 3% vis-a-vis the US dollar in the first three months of 2014, a sharp departure from the 3% appreciation witnessed in 2013 (Graph 1). This weakness is unprecedented in both length and extent since the RMB was first de-pegged from the US dollar in 2005.

The Chinese renminbi (RMB) depreciated by as much as 3% vis-a-vis the US dollar in the first three months of 2014, a sharp departure from the 3% appreciation witnessed in 2013 (Graph 1). This weakness is unprecedented in both length and extent since the RMB was first de-pegged from the US dollar in 2005.

On 15 March 2014, the People’s Bank of China (PBC), the Chinese central bank, widened the daily RMB trading band from ±1% to ±2% against the dollar, indicating that it will refrain from regular FX interventions in the future unless the market behaves abnormally.

Is the latest round of RMB weakness policy or market induced? Is the PBC primarily aiming for a weak currency policy or two-way currency volatility? Does the latest surprise PBC move achieve its policy objectives?

Graph 1: RMB daily closing as a % change from the fixing

Note: Daily appreciation or depreciation as a percent of the central parity, against the US$. Positive (negative) value means depreciation (appreciation) of the daily closing from the daily central parity (fixing).

Sources: Datastream.

There are two competing explanations for the latest RMB movements.

First, the PBC sought to break the stubborn one-way appreciation expectation of the Chinese currency and flush out the rampant RMB carry trade by instilling two-sided exchange rate volatility. In this case, the observed RMB weakness was policy-induced.

Alternatively, the US Fed tapering and concerns about China’s debt overhang and growth slowdown dampened market sentiment and triggered capital outflows from China, thereby weakening the RMB. In this case, it was simply a market-induced depreciation.

Or possibly, the PBC seized the moment of market uncertainty to push the RMB even weaker and succeeded in introducing a sense of two-way risk that may deter hot money inflows, weakening the RMB. If these two stories are taken to be complementary, the question arises of how to weigh these policy and market factors.

There are clear footprints of policy interventions in this episode of notable RMB weakness. One tool the PBC uses to manage the RMB exchange rate is setting the fixing as the central parity for the daily trading band against the US dollar. Market participants take the fixing as a key policy signal. During the first quarter of 2014, the US dollar was broadly stable or weaker against other major currencies, as indicated by the Federal Reserve DXY index. Had the PBC have pursued its characteristic basket management of the RMB along an effective appreciation path of 2-3% per annum (Ma and McCauley (2011)), one would have expected a stronger fixing against the dollar on average.

In other words, the basket approach would have suggested that the renminbi fixing split the difference between the (stronger) euro and (weaker) dollar. Instead, the fixing weakened by 1% in the first quarter, compared to its 3% strengthening in 2013.

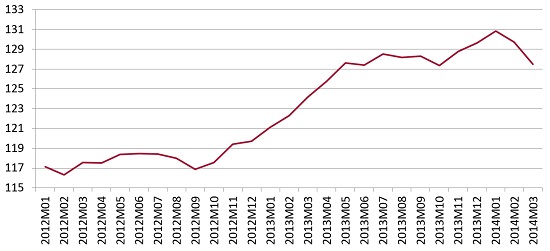

Indeed, the Bruegel REER statistics show that the effective RMB depreciated two months in a row in February and March 2014 (Graph 2). Moreover, the daily fixing appears to have become more unpredictable, deviating more often from the forecasts of market participants based on some sort of basket management and doubling its realised volatility from its lows seen in early January.

Graph 2: The real effective exchange of the renminbi (December, 2007=100)

Source: Bruegel.

Another PBC tool to manage the RMB is direct or indirect buying/selling of dollars and RMB in the FX market, which interacts with market forces to influence the daily closing. In the first quarter this year, the RMB closed half the time on the strong side and half the time on the weak side of its daily trading band, compared to almost 100% at the strong side in 2013 (Graph 1).

The PBC could bid for dollars to weaken the RMB, or the RMB itself could weaken on capital outflows triggered by bearish sentiment towards China. Indeed, China’s current account balance registered smaller quarterly surplus in a decade first quarter during January-March. A key difference is that in the former case, the RMB liquidity would loosen and the interbank interest rate would fall unless the PBC drains sufficient liquidity, while in the latter case, the RMB liquidity would tighten and the interbank rate would rise unless the PBC injects sufficient liquidity.

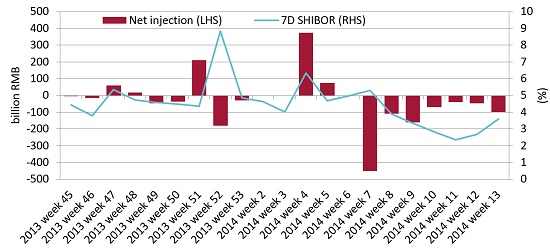

The first quarter simultaneously witnessed PBC liquidity withdrawals through domestic credit operations, mostly falling interbank interest rates and a weaker RMB, suggesting that at least in the initial phase, the PBC might have aggressively purchased dollars to push the RMB weaker without mopping up the resulting RMB liquidity fully (Graph 3).

However, forceful direct FX interventions appeared to have mostly taken place between mid-January and mid-February and eased off by late February. According to the latest PBC statistics, two thirds of the first quarter’s US$129bn FX reserve accumulation occurred in January. By the way, as much as half of this reported FX reserve accumulation could arise from valuation effects (say due to a stronger euro) rather than simple dollar buying by the PBC over the quarter.

Graph 3: Net liquidity injection from OMOs and 7-day SHIBOR

Note: Weekly net liquidity injection (+) or withdrawal (-) of PBC open market operations.

Sources: the PBC and Datastream.

Some may argue that the PBC pursued a weak currency policy to support the Chinese economy in the context of a weaker economy and easing inflation. China’s GDP growth eased to 7.4% year-on-year, the slowest pace in recent years. But I doubt this is the principal motive, unless the economy is in much deeper trouble than most analysts reckon.

Instead, the PBC might have chosen to surprise RMB carry traders, in order to deter speculative inflows, as it plans to step back from regular FX interventions and to open more of the capital account. Significant carry trades have been funded by sizable bank inflows into China in recent years, giving the PBC big headaches. The Chinese statistics suggest that foreign bank inflows rose more than 50% in 2013, and in the first quarter this year, lending by Hong Kong banks to Chinese firms soared 40% over a year ago, potentially complicating both monetary management and financial stability. Ironically, banks flows have so far received scant attention in the discussion of China’s prospective capital account liberalisation (Ma and McCauley (2014)).

Such carry trading inflows are enticed by a lucrative mix of low US dollar yields, higher RMB yields amidst domestic financial liberalisation and very low FX volatility until mid-January. The differential between 3-month SHIBOR and LIBOR recently stood at 4-5%, with the implied volatility of the RMB only one third to one fifth of the other major emerging market currencies. Indeed, an ex ante measure of risk-adjusted returns on RMB money market carry trades indicates that the RMB is among the most attractive carry trade targets, providing strong incentives for both domestic firms and foreign investors to arbitrage and bypass capital controls via trade mis-invoicing and commodity financing (Graph 4).

So the PBC might have aimed to instigate greater currency volatility by its surprise move, to disrupt the dynamics of one-way betting. During the first quarter, the RMB’s option-implied volatility doubled, and thus its carry-to-risk ratio halved, possibly slowing hot money inflows and even prompting some unwinding of short dollar positions in late February and March. The realised volatility of the RMB spot also jumped three or four times from the low levels seen before the PBC move. Effectively, the PBC has for now managed to engineer a weaker RMB, keep local short rates down and provoke greater currency volatility at the same time, delivering a triple blow to carry traders who profited from a steady RMB appreciation and a juicy positive carry.

The 12-month RMB deliverable forwards, both onshore and offshore, as well as their non-deliverable counterpart, all started by late February pricing in more RMB depreciation vis-a-vis the US dollar. A wider trading band, together with sporadic dollar bids and a weaker and more uncertain fixing, might have helped curb the one-way RMB appreciation expectations and contain speculative inflows.

Graph 4: Sharpe ratios for selected emerging market currencies1

1 Defined as the three-month interest rate differential divided by the implied volatility derived from three-month at-the-money exchange rate options for the relevant currency pair.

Source: Bloomberg and BIS staff calculations.

This is much welcome, as the reform-minded PBC is negotiating a tricky transition away from a convoluted regime featuring a heavily managed currency, a heavily controlled capital account and a heavily regulated domestic interest rate.

Nevertheless, the game is far from over. First, our simple version of the Sharpe ratio suggests that even after the recent market shakeout, the RMB remains quite attractive for carry traders relative to many other emerging market currencies. Second, the PBC has to walk a tightrope carefully. A sustained RMB weakness may invite international criticism (and “serious concerns”) or trigger disorderly outflows in the context of higher FX volatility and the US Fed tapering, while a premature end to the policy-induced RMB weakness may signal a cap on the risks to RMB carry trade, potentially prompting even more speculative inflows into China. Third, the ongoing RMB internationalisation (see Jim O’Neill, Guonan Ma and Xi Qiyuan‘s comments) and prospective capital account liberalisation agenda may add to the challenges of this balancing act.

***

Reference:

Ma, G and R McCauley (2011): “The evolving renminbi regime and implications for Asian currency stability”, Journal of the Japanese and International Economies, March, No 25, pp 23-38.

Ma, G and R McCauley (2014): “Financial openness of China and India — Implications for capital account liberalisation”, China Update, Australian National University Press, forthcoming.

Assistance by Carlos de Sousa is gratefully acknowledged)

Republishing and referencing

Bruegel considers itself a public good and takes no institutional standpoint. Anyone is free to republish and/or quote this post without prior consent. Please provide a full reference, clearly stating Bruegel and the relevant author as the source, and include a prominent hyperlink to the original post.