Blog Post

The impact of COVID-19 restrictions on individual mobility

Distancing measures imposed by twelve European countries during the COVID-19 pandemics (a ban on holding public events, school closures, shop closures, and a ban on non-essential movement) were associated with large drops in visits to retail and recreation, groceries and pharmacies, transit stations, and workplaces, drops in visits to parks in most cases, and an increase in time spent at home. These effects, measured and disentangled in our analysis, have implications for the costs and risks of closing and re-opening economies: distancing policies (i) reduced contact and likely reduced the transmission of COVID-19 within the population, implying gains for public health, while they (ii) reduced presence at workplaces, shops, restaurants and other venues of economic activity, implying economic costs.

The COVID-19 pandemic that hit Europe during the first quarter of 2020 had claimed tens of thousands of lives by the end of April. As the number of daily new infections and deaths started to level off or even slowly decline in April, a discussion began as to how restrictions can be selectively lifted. This discussion was reflected at the European level in the roadmap issued on 15 April 2020 (European Commission, 2020).

A vaccine is unlikely to be widely distributed before mid-2021 (Veugelers and Zachmann, 2020). The availability of effective medication and the emergence of widespread herd immunity in the European population seem to be similarly remote. The economy will therefore have to be restarted while COVID-19 is still an active and immediate threat. A smart targeted containment coupled with an economic restart is needed to curtail human and economic losses.

In order to gauge the potential impact of easing or introducing COVID-19 restrictions, policymakers need to better understand to what extent the restrictions already imposed have succeeded in reducing contact and thus slowing the spread of COVID-19, as well as their economic cost.

Since quantitative data on actual contacts in Europe has not historically been publicly available, we have combined Google data on the mobility of individuals (Google LLC, 2020) with information about the mobility restrictions imposed in a number of EU countries and in the UK in order to evaluate the degree to which restrictions have been effective in reducing contact.

Methodology for measuring mobility and distancing policies

Beginning late March 2020, Google published a new source of mobility data (Google LLC, 2020) based on the same location data they use to indicate busy hours for restaurants and museums (see Aktay et al, 2020). Since data is captured only from users who have opted in to ‘location history’ on their Android devices, it raises no new privacy concerns[1]. The data is aggregated and anonymised (and some random noise is introduced) in order to maintain the privacy of the individuals whose data is used. All metrics for which the differentially private count of contributing users (after noise addition) is smaller than 100, or for which the geographic region is smaller than 3km2, are discarded (Aktay et al, 2020).

The Google data covers the period from 16 February to 11 April 2020. It compares visits and length of stays at the following six kinds of institutions or venues with the historic baseline[2] (Aktay et al, 2020):

- retail & recreation (including restaurants, cafes, shopping centres, theme parks, museums, libraries and cinemas);

- grocery & pharmacy (including grocery markets, food warehouses, farmers markets, specialty food shops, drug stores and pharmacies);

- parks (including national parks, public beaches, marinas, dog parks, plazas and public gardens);

- transit stations (public transport hubs such as subway, bus and train stations);

- workplaces;

- residential (“an average amount of time spent at places of residence … in hours” for all users in the sample, which thus represents time spent in all residences, not necessarily in the individual’s own residence).

The Google data does not represent a perfect random sample of the general population as users of Android[3] smartphones and tablets may differ from the general population in terms of various demographic, social and economic characteristics, including disposable income and digital literacy. Furthermore, Android users who grant usage of their data may also be a non-random sub-sample. Nonetheless, the reported trends are based on such a large amount of data that any biases are probably not critical to an understanding of broad changes in mobility (the market share of the Android operating system in Europe is about 70%[4]).

We selected twelve European countries based on the availability of distancing policy data: Austria, Belgium, Czechia, France, Germany, Hungary, Italy, Poland, Portugal, Slovakia, Spain and the United Kingdom. All except the UK are EU member states.

The data on distancing policy measures comes from Hale et al (2020) and other publicly available sources (PHA SR, 2020; PIB, 2020).

We focused on four restrictions that had been imposed by 31 March 2020 in most of the 12 European countries studied:

- the prohibition of public events (with more than a specified number of attendees);

- the closing of schools;

- the closing of non-essential shops;

- the prohibition of non-essential movement from the residence.

Effects of distancing policies

As a first step, we studied mobility trends with respect to the date on which the respective policy measure came into force, setting this date to be day 0 and transposing the data series forward or backward accordingly.

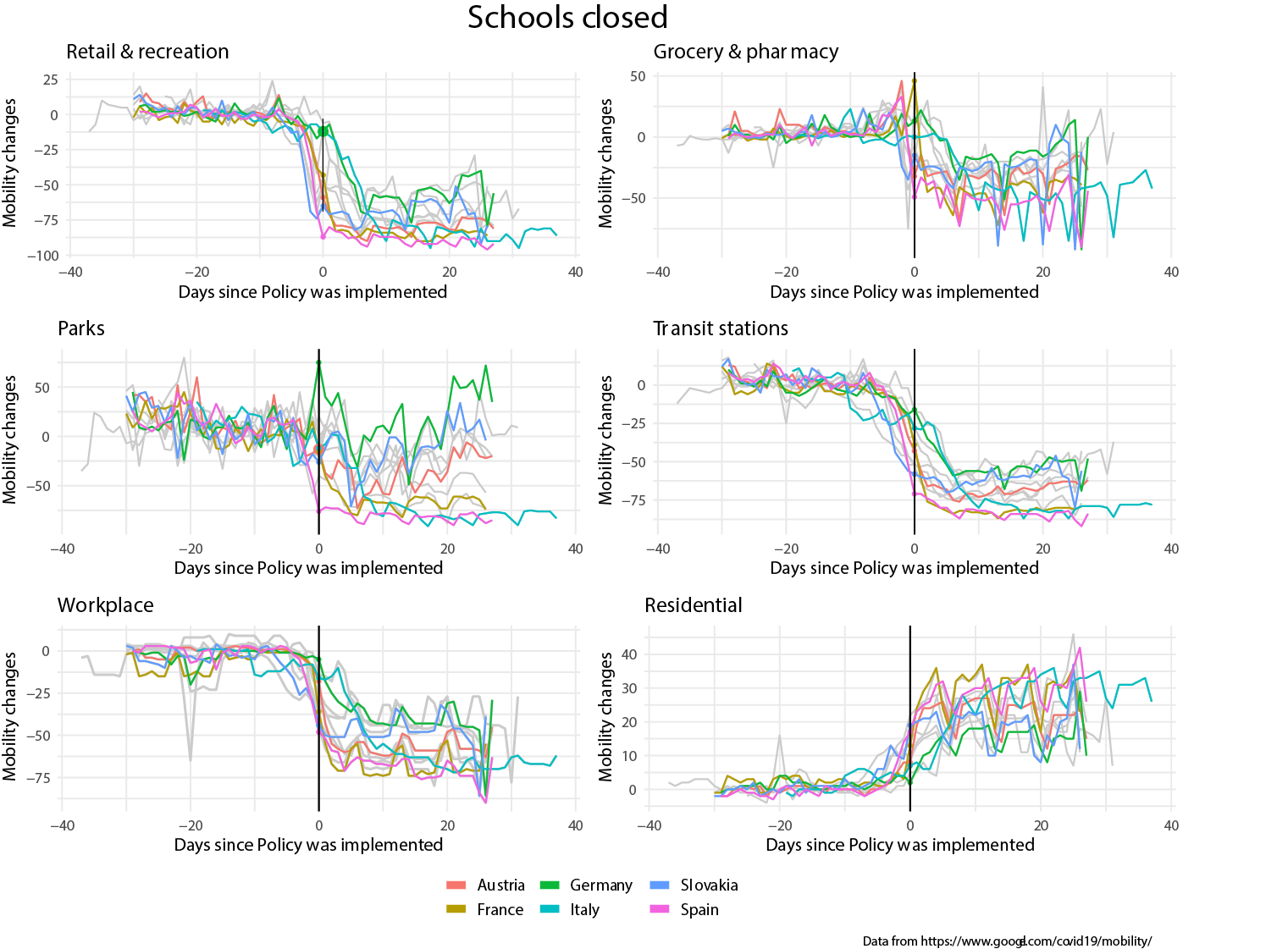

Figure 1 shows that schools closures are strongly associated with changes in mobility trends in all of the European countries in which they were imposed. Similar changes in mobility trends emerge for the other three measures that we studied (not reported). Overall, mobility was reduced in lock-step with the introduction of additional formal restrictions. Among the twelve countries that we studied, we have highlighted Austria, France, Germany, Italy, Slovakia, Spain and Sweden.

Figure 1: The impact of closing of schools on different forms of mobility in selected EU countries

Source: Bruegel based on data from https://www.google.com/covid19/mobility.

Source: Bruegel based on data from https://www.google.com/covid19/mobility.

Specifically, as one might have expected, each of the restrictions is associated with a drop in visits to retail and recreation, transit stations and workplaces. The reduction of trips to groceries and pharmacies was smaller, which is unsurprising because the demand for food and medical supplies is rather inelastic and because people were still allowed to go out to purchase the essentials. It is equally unsurprising that time spent at home increased as a result of the restrictions. The effect on mobility in parks is more diverse, reflecting the variation in the strictness of the regulations imposed.

Different restrictions could be expected to impact different kinds of mobility in different ways. In order to disentangle the independent effects of the policy measures studied, we have employed a simple statistical analysis that estimates the incremental impact that each of the measures studied had on mobility since the date on which the measure was implemented[5]. The size of the estimated impacts can be interpreted as a net effect of a given policy on mobility in percentage points and is specific to the type of mobility that is considered.

The mobility patterns observed suggest that people might have responded to the health risks of COVID-19 above and beyond what was required by the formal distancing policy measures (see also Midões, 2020, and Toxvaerd, 2020). To account for such a possibility of self-isolation, we have included in the regression model six control variables that approximate the spread of the disease in the country, controlling for the incremental effects on mobility of the first, thousandth and hundredth, and thousandth reported death in each particular country.[6] Additionally, we added controls for bank holidays and the days of the week in the model to account for the possibly that the role of weekdays was changing over time beyond the baseline due to seasonality of mobility patterns.

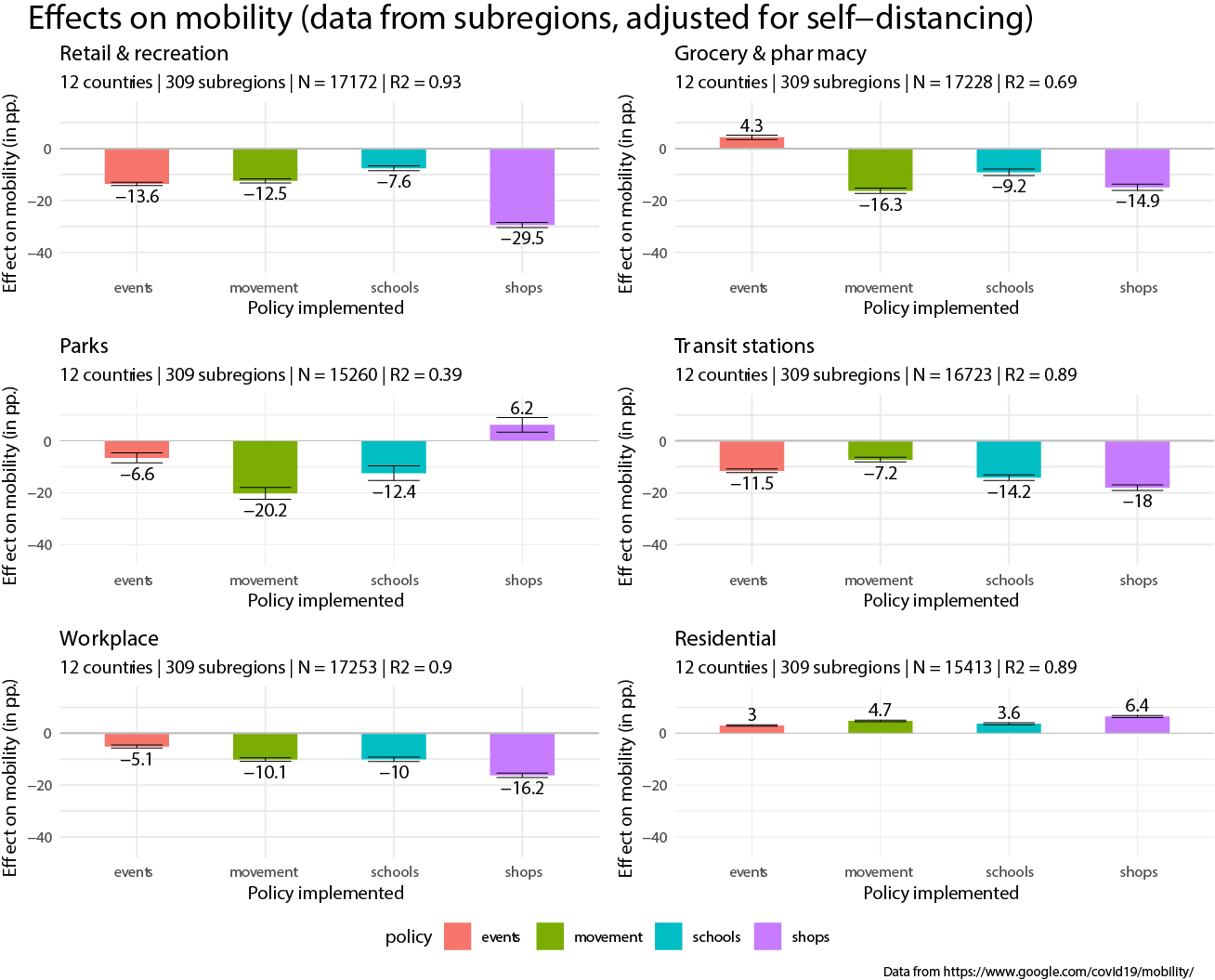

The results, reported in Figure 2, indicate that a prohibition on public events (ie on events with a number of participants in excess of some threshold) is associated with fewer visits and shorter stays in shops, recreation areas, transit stations and, to a lesser extent, visits to parks and places of work. Trips to groceries and pharmacies increase slightly (possibly due to the substitution effect), as does time spent at home.

Figure 2: The impact of four different kinds of restrictions on mobility for twelve selected European countries (with corresponding 95% confidence intervals)

Source: Bruegel based on data from https://www.google.com/covid19/mobility/.

Source: Bruegel based on data from https://www.google.com/covid19/mobility/.

Closing of schools correlates with a decrease of frequentation of transit stations, parks and workplaces (likely because some parents must stay home to care for their children), and to a lesser extent of shops, recreation areas, groceries and pharmacies. On the other hand, people spend more time in places of residence.

Shop closures have a strong negative association with all mobility except for increased time spent at home and in parks. This may indicate that shop closures divert people into parks, although we should note the relatively large standard deviation of the estimate for parks.

Restrictions on non-essential movement from the residence appear to have reduced all forms of mobility, especially in parks, groceries and pharmacies, retail and recreation, and resulted in an increase of time spent at home.

The estimated effects of the information about the spread of the disease (cases and deaths) corroborates the view that people responded to the pandemic by reducing their mobility above and beyond the formal distancing policies.

We have performed several robustness checks on our results: alternative measures of the spread of COVID-19 as a way to account for self-distancing in the models, controls for the Carnival period, and a ‘placebo’ policy with a (uniformly) randomly generated date of implementation for each country. Our results turned out to be very robust with respect to these alternative specifications.

We acknowledge several limitations of our analysis with respect to its policy implications: the estimated associations represent the average net effects for the twelve countries studied, hiding any cross-country variation; we ignored any inertia or delays in the effects; revoking a regulation may impact mobility differently, in terms of both its size and speed, than imposing it; and although we are inclined to believe that a significant part of the observed changes in mobility patterns was driven by the studied distancing policies, we cannot rule out reverse causality, ie the policy changes that we are looking may have been in part, directly or indirectly, a response to changes in mobility patterns that were already visible or expected.

Despite all these limitations, judging by the measure of fit of these regressions, we believe our analysis provides a simple and reasonable account of the mobility patterns and the role of mobility policies.

Implications for public policy

Several countries, in Europe and elsewhere, have initiated or are considering a gradual easing of restrictions (see also European Commission, 2020). One could envisage a staged reopening starting with those deregulations with lowest risk and/or highest return first, while high-risk options (eg public events) would reopen last.

Decisions about easing of restrictions, as well as any re-imposition of restrictions as new flare-ups of infection possibly occur, need to take into account the possible effect of specific restrictions on mobility.

The analysis presented in this blog post quantifies and disentangles the various effects. Considering that reduction in mobility at places of work, retail and recreation, groceries and pharmacies, or other venues affects productivity and aggregate demand, it also sheds light on the costs of the studied restrictions.

Key observations from this analysis:

- Each of the four distancing policy measures studied is associated with a sharp decline in observed mobility patterns in Europe.

- The cancellation of public events seems to have less impact on most forms of mobility than the other measures we have covered, although it appears to have triggered the voluntary adjustment in mobility patterns, being the first major distancing policy implemented in most countries.

- School closures appear to have a significant negative impact on all forms of mobility outside the residence. Closing of shops seems to have a similar, and in many cases larger, negative effect on mobility. We note, however, that it is difficult to fully disentangle their effects because schools and shops often closed at nearly the same time.

- Imposition of restrictions on non-essential movement appears to have significant impacts on mobility.

- Our analysis suggests that people responded to reported COVID-19 cases and deaths and self-isolated above and beyond any formal legal restrictions imposed.

These effects of mobility restrictions are likely to have slowed the spread of the disease. At the same time, the significant drops in visits to the workplace are likely to be associated with regrettable loss of productivity (depending on the nature of the work done, and its being amenable to telework) and disruptions to value chains. In addition, the declines in mobility in other areas, most notably retail, recreation, groceries and pharmacies, are likely to cost livelihoods in those sectors (especially those not amenable to online provision). Our analysis informs the debates about these trade-offs by quantifying the underlying impacts on mobility.

Acknowledgements

Martin Kahanec gratefully acknowledges the Mercator Senior Fellowship at Bruegel during the work on this blog. The authors thank Enrico Bergamini for providing us with the data used in an earlier draft of this blog.

References

Aktay, A., S. Bavadekar, G, Cossoul, J. Davies, D. Desfontaines, A. Fabrikant … R.J. Wilson (2020) ‘Google COVID-19 Community Mobility Reports: Anonymization Process Description (version 1.0)’, mimeo

European Commission (2020) Joint European Roadmap towards lifting COVID-19 containment measures, available at https://ec.europa.eu/info/sites/info/files/communication_-_a_european_roadmap_to_lifting_coronavirus_containment_measures_0.pdf

Google LLC (2020) Google COVID-19 Community Mobility Reports, accessed 21 April 2020, available at https://www.google.com/covid19/mobility/

Hale, T., S. Webster, A. Petherick, T. Phillips and B. Kira (2020) Oxford COVID-19 Government Response Tracker, Blavatnik School of Government, available at https://www.bsg.ox.ac.uk/research/research-projects/coronavirus-government-response-tracker

Midões, C. (2020) ‘Social distancing: did individuals act before governments?’ Bruegel Blog, 7 April, available at: https://wordpress.bruegel.org/2020/04/social-distancing-did-individuals-act-before-governments/

Presse- und Informationsamt der Bundesregierung (PIB) (2020) ‚Vereinbarung zwischen der Bundesregierung und den Regierungschefinnen und Regierungschefs der Bundesländer angesichts der Corona-Epidemie in Deutschland‘,Nr. 96, 16 March, Federal Government of Germany

Toxvaerd, F. (2020) ‘Equilibrium Social Distancing’, Cambridge Working Papers in Economics: 2021, available at https://www.inet.econ.cam.ac.uk/working-paper-pdfs/wp2008.pdf

Veugelers, R. and G. Zachmann (2020) ‘Racing against COVID-19: a vaccines strategy for Europe’, Policy Contribution 7/2020, Bruegel, available at https://wordpress.bruegel.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/04/PC-07-2020-210420.pdf

[1] According to Aktay et al (2020), the mobility time series are created from anonymised and aggregated data from users who have opted in to location history, which is off by default on their Android devices. Location history can be turned on and off from their Google accounts and location history data can be deleted directly from their timelines.

[2] The baseline is the median value, for the corresponding day of the week, during the 5-week period 3 January – 6 February 2020.

[3] Nearly all smart phones and tablets except for those provided by Apple are in this category.

[4] Statcounter GlobalStats, available at (accessed on April 27, 2020): https://gs.statcounter.com/os-market-share/mobile/europe?fbclid=IwAR2Qyf-43sTxCVu9-77tL5CRJRzQ4lwmW2_3EoLA9vlMmudROnLSdNiBoCc

[5] Specifically, we used a linear regression model in which we approximated the policy impacts on mobility by a step function where steps occur on the dates when particular policies were implemented. We fitted a step function to mobility patterns observed in the twelve countries at the level of sub-regions (top-level geopolitical subdivision within countries).

[6] Similarly as for the policy variables, we modelled the impacts of the spread of the disease on mobility using a step function where steps occur on the dates when the respective cases or deaths were announced.

Recommended Citation:

Kahanec, M., L. Lafférs and J.S. Marcus (2020) ‘The impact of COVID-19 restrictions on individual mobility’, Bruegel Blog, 5 May

Republishing and referencing

Bruegel considers itself a public good and takes no institutional standpoint. Anyone is free to republish and/or quote this post without prior consent. Please provide a full reference, clearly stating Bruegel and the relevant author as the source, and include a prominent hyperlink to the original post.