Blog Post

Is COVID-19 triggering a new emerging-market crisis?

Emerging economies have received little attention in the economic debate regarding the COVID-19 pandemic, yet the performance of their primary market indicators, chiefly sovereign debt, foreign exchange and equities, indicate a deep deterioration is taking place. Times of crisis often lead to capital flight from emerging markets as investors seek safe haven assets, while the localised effects of the disease and the collapse in the price of certain key commodities have also been damaging. More worryingly, this appears to be the beginning of the storm, and emerging economies have far less room for fiscal and monetary manoeuvring.

COVID-19 has yet to hit most emerging-market economies (EMEs) to the extent it has affected the European Union and the United States. China and Iran are exceptions. Nevertheless, the incipient global recession and widespread market contagion have already resulted in substantial deterioration in EME macroeconomic and financial indicators.

Starting from the third week of February 2020, most EMEs experienced increasing market stress (Figures 1-4). Market conditions further deteriorated in the first two weeks of March when the depth of economic damage beyond East Asia became more obvious.

Figure 1 shows the spread (in basis points) between 10-year dollar-denominated government bonds and 10-year US Treasury bonds, for selected countries. The bonds are valued in dollars and are thus not subject to exchange-rate fluctuations, but the weakening of emerging-market currencies has increased the perceived risk of default and can be seen as the primary determinant of fluctuations. Figure 2 shows credit default swaps (CDS), which reflect the market-determined probability of default. The correlation between CDS and spreads is unsurprisingly high, as both reflect changes in relative market confidence in individual country’s sovereign solvency.

For all analysed countries, spreads against US Treasuries have grown, providing a good indication of increasing risk aversion and fear of sovereign default. CDS have exhibited a similar pattern.

Figure 3 shows data on exchange rate depreciation against the dollar. In Brazil, Colombia, Uruguay and South Africa the depreciation has exceeded 15%, while in Russia and Mexico it has exceeded 20%. Such substantial depreciation, if not reversed quickly, could have serious inflationary consequences. However, it is important to note that, differently from spreads and CDS, cross-country differences in exchange-rate depreciation reflect not only country-specific vulnerabilities, but also variations in exchange-rate regimes. Countries with fixed exchange rates or heavily managed floats have not recorded changes in the exchange rates of their currencies, or have recorded limited changes (for example, Gulf countries and several Asian countries). In those cases, market pressures resulted in central bank intervention on foreign exchange markets and decreasing international reserves (lack of short-term data on changes in international reserves does not allow for analysis of these kinds of effects).

Finally, Figure 4 shows changes in stock market indices. While their decline looks, at first glance, significant, it is largely in line (or even smaller) with what has been seen in advanced economies (for example, the Eurostoxx 50, the main European index, fell by around 35% during the same time period). However, stock markets in EMEs are often less liquid then those in advanced economies, which could limit the effect to which they reflect genuine market valuations.

Global versus country specific factors

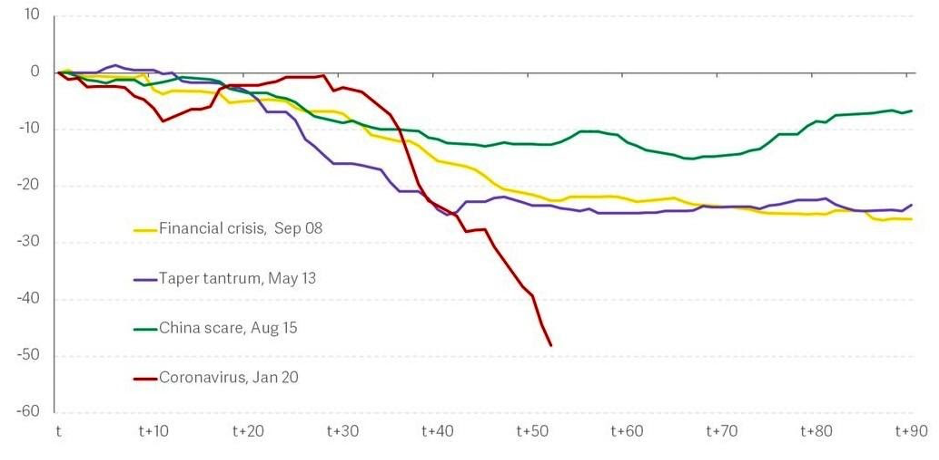

All of these changes in macroeconomic and financial indicators reflect a massive capital outflow from EMEs, larger than during other global shocks since 2008 (see Lanau and Fortun, 2020, and Figure 5). The increased risk aversion and global uncertainty caused by the COVID-19 pandemic has pushed investors to move their capital from emerging-market assets to so-called safe havens (for example, US Treasury bonds).

Figure 5: Cumulative non-resident portfolio flows to EMEs in times of global shocks, time in number of days, in US$ billions

Source: Lanau and Fortun (2020).

Apart from global, there are regional and country-specific factors. Despite being the original epicentre of the pandemic, China remained almost unaffected according to the analysed metrics. Other countries of East and South Asia, except for Indonesia and Philippines, look to have been only mildly affected. This might reflect both the incomplete integration of their financial markets and market perception of their relatively strong macroeconomic fundamentals. In Eastern Europe, Hungary, Poland and Romania have also been mildly affected. Here, EU membership seems to serve as a kind of insurance.

Commodity producers have also been hit by the price decline, again similarly to 2008-2009. The collapse of the OPEC-plus cartel in early March 2020 sent the already decreasing price of crude oil down further (Poitiers and Domínguez-Jiménez, 2020). This is reflected in the considerable deterioration of market indices recorded by countries including Mexico, Russia, Nigeria, Colombia, Brazil and Indonesia.

Finally, countries that have previously had problems with macroeconomic and financial stability (for example, Argentina, Costa Rica, Nigeria, Pakistan, Turkey and Ukraine) have been hit harder than others. Here, one can make an analogy with patients with pre-existing illness who are at higher risk if they are infected by coronavirus.

What might happen and what should be done?

This may be only the beginning of the storm. In the coming weeks and months, macroeconomic and financial turbulence could continue and grow as the result of recession in the US and Europe, increasing numbers of COVID-19 cases in EMEs, potential disruption of supply chains and shrinking demand for goods and services produced by EMEs (tourism, for example). Monetary policy easing in advanced economies, especially in the US, and swap lines between the US Federal Reserve System and some EME central banks, could provide a partial cushion.

Most EMEs should be extremely careful with their own monetary and fiscal measures. Their macroeconomic room for manoeuvre is more limited compared to advanced economies because of the limited credibility of emerging-market currencies (Dabrowski, 2016). Overly aggressive stimulation could trigger capital flight and currency substitution. The financial aid should come, at least partly, from outside.

This is a primary mission of the International Monetary Fund, which should be prepared to provide immediate financial assistance to distressed EMEs, as it did from 2008 to 2010. This time, the IMF seems to be sufficiently funded (having around US$1 trillion at its disposal), although nearly 80 countries have already asked for its support (Georgieva, 2020).

The G20 also has a role to play. It can provide a coordinated policy response to the crisis and fight protectionism and other beggar-thy-neighbour policies, as it did from 2008 to 2010 (Bery et al, 2019).

If EMEs sink deeper into macroeconomic and financial chaos, it will magnify a negative shock to the entire world economy, including advanced economies and their financial sectors.

References

Bery, S., F. Biondi and S. Brekelmans (2019) ‘Twenty years of the G20: Has it changed global economic governance?’, Russian Journal of Economics 5(4): 402-440, DOI 10.32609/j.ruje.5.49435

Dabrowski, M. (2016) ‘Core and periphery: different approaches to unconventional monetary policy’, Bruegel Blog, 24 May, https://wordpress.bruegel.org/2016/05/core-and-periphery-different-approaches-to-unconventional-monetary-policy/

Georgieva, K. (2020) ‘IMF Managing Director Kristalina Georgieva’s Statement Following a G20 Ministerial Call on the Coronavirus Emergency’, IMF Press Release No. 20/98, 23 March, https://www.imf.org/en/News/Articles/2020/03/23/pr2098-imf-managing-director-statement-following-a-g20-ministerial-call-on-the-coronavirus-emergency

Lanau, S. and J. Fortun (2020): ‘The COVID-19 Shock to EM Flows’, Economic Views, Institute for International Finance, 17 March, https://www.iif.com/Portals/0/Files/content/EV_03172020.pdf

Poitiers, N. and M. Domínguez-Jiménez (2020) ‘COVID-19 and broken collusion: the oil price collapse is one more warning for Russia’, Bruegel Blog, 19 March, https://wordpress.bruegel.org/2020/03/covid-19-and-broken-collusion-the-oil-price-collapse-is-one-more-warning-for-russia/

Republishing and referencing

Bruegel considers itself a public good and takes no institutional standpoint. Anyone is free to republish and/or quote this post without prior consent. Please provide a full reference, clearly stating Bruegel and the relevant author as the source, and include a prominent hyperlink to the original post.