Blog Post

Blaming the Fed for the Great Recession

What’s at stake: Following an article in the New York Times by David Beckworth and Ramesh Ponnuru, the conversation on the blogosphere was dominated this week by the question of whether the Fed actually caused the Great Recession. While not mainstream, this narrative recently received a boost as Ted Cruz, a Republican candidate for the White House, championed it.

An alternative story

David Beckworth and Ramesh Ponnuru write that it has become part of the accepted history of our time: The bursting of the housing bubble was the primary cause of a financial crisis, a sharp recession and prolonged slow growth. The story makes intuitive sense, since the economic crisis included a collapse in the prices of housing and related securities. But there is an alternative story.

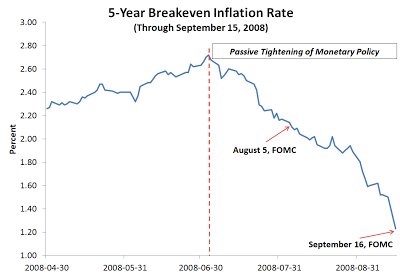

David Beckworth writes that the Fed began to passively tighten during the second half of 2008. A passive tightening of monetary policy occurs whenever the Fed allows total current dollar spending to fall, either through a fall in the money supply or through an unchecked decrease in money velocity. Such declines are the result of firms and households expecting a worsening economic outlook and, as a result, cutting back on spending. In such settings, the Fed could respond to and offset such expectation-driven declines in spending by adjusting the expected path of monetary policy. But the Fed chooses not do so and this leads to a passive tightening of monetary policy.

Arnold Kling writes that this is an easy argument to make. A recession is, almost by definition, the economy operating below potential. Operating below potential is, almost by definition, a shortfall in aggregate demand. The Fed controls aggregate demand. Therefore, all recessions are the fault of the Fed. Either by commission or omission, the Fed has messed up if we have a recession.

Source: Macro Market Musings

David Beckworth writes that the FOMC allowed the declining inflation expectations to form by failing to signal an offsetting change in the expected path of monetary policy in both its August and September 2008 FOMC meetings. Prior to the September 16 FOMC meeting the breakeven spread declined from a high of 2.72 percent in early July to 1.23 percent on September 15. One way to interpret this decline is that the bond market was signaling it expected weaker aggregate demand growth in the future and, as a result, lower inflation. Even if part of this decline was driven by a heightened liquidity premium on TIPs the implication is still the same: it indicates an increased demand for highly liquid and safe assets which, in turn, implies less aggregate nominal spending.

George Selgin writes that in contrast to the Fed’s actions in August 2007, its subsequent turn to sterilized lending had it, not buying, but selling Treasury securities, with the aim of preventing its emergency lending from resulting in any overall increase in the supply of bank reserves. Financial conditions were thus “eased,” not generally, but for particular institutions and their creditors. For the rest, credit was actually tightened.

Monetarism then and now

David Beckworth writes that the worst part of the financial crisis took place after the period of passive Fed tightening. This is very similar to the 1930’s Great Depression when the Fed allowed the aggregate demand to collapse first and then the banking system followed.

Paul Krugman writes that this is a repeat of the old Milton Friedman two-step. First, you declare that the Fed could have prevented a disaster — the Great Depression in Friedman’s case, the Great Recession this time around. Then this morphs into the claim that the Fed caused the disaster. Paul Krugman writes that Friedman and Schwartz argued that the Fed could have prevented the Depression by aggressively expanding the monetary base to prevent a sharp fall in broader monetary aggregates. In the Great Recession, the argument is that the Fed did in fact “passively” tighten by failing to do enough to offset falling spending.

Monetary impulse and the size of the downturn

Mike Konczal writes that if your mental model is that the Federal Reserve delaying something three months is capable of throwing 8.7 million people out of work, you should probably want to have much more shovel-ready construction and automatic stabilizers, the second of which kicked in right away without delay, as part of your agenda. It seems odd to put all the eggs in this basket if you also believe that even the most minor of mistakes are capable of devastating the economy so greatly.

Scott Sumner writes that the financial crisis as a whole would have been far milder if the Fed had kept NGDP growing at roughly 5%/year. And the reason is simple; at that growth rate the asset markets would have been far stronger, and the crash in asset prices severely impacted the balance sheets of many banks, including Lehman. Keep in mind that the subprime crash was not big enough to bring down the banking system. Rather when NGDP growth expectations plunged, the prices of homes in the (non-bubble) heartland states, as well as commercial property, began falling. This is what turned a manageable financial crisis into a major crisis.

Paul Krugman writes that if there were anything to this story, we should have seen a sharp increase in long-term real interest rates, as investors saw the Fed getting behind the disinflationary curve.

Republishing and referencing

Bruegel considers itself a public good and takes no institutional standpoint. Anyone is free to republish and/or quote this post without prior consent. Please provide a full reference, clearly stating Bruegel and the relevant author as the source, and include a prominent hyperlink to the original post.