Blog Post

Opaque Europe: financial supervisory transparency, why it’s important, and how to improve it

“Financial supervisory transparency” has been on the agenda of international financial institutions for some time. It concerns the public availability of data supervisors have on the financial industry. Using a new measure of data reporting to international financial institutions like the IMF and World Bank, we show that financial supervisory transparency is particularly lacking in Europe. We make recommendations for EU institutions to improve it.

Transparency is important. It provides markets and voters with more information about the relative health of a country’s financial sector. Our empirical work shows that market actors penalise countries with less supervisory transparency when they have high debt levels. The reason is that markets do not know what other liabilities the government may face, and they punish the less transparent countries with higher interest rates. Transparency is also relevant for increasing the ability of voters to hold their institutions accountable.

Consequently, transparency has been lauded as enhancing market stability and democratic legitimacy. The International Monetary Fund (IMF) and the Basel Committee for Banking Supervision have pushed supervisors to release financial data they have to the public. Within the European Union, the European Banking Authority (EBA) has made a number of recent attempts to promote transparency, as have other EU financial sector institutions, such as the the European Central Bank (ECB) and the European Insurance and Occupational Pensions Authority (EIOPA).

Measuring Transparency

While there seems to be a consensus that there should be more supervisory transparency, measuring whether or not supervisors are transparent is difficult. To date, there has been no measure of transparency that is broadly comparative across countries or captures whether supervisors make macro-prudential data public. In order to address this gap, we created a new indicator called the Financial Regulatory Transparency (FRT) Index. It measures whether countries report core macro-prudential data about their financial systems to international financial institutions like the International Monetary Fund and World Bank.

Details appear in our Bruegel Policy Contribution, but readers should note that this is not a “normal” index that simply adds up the number of times a country reports a piece of supervisory data. Instead, we create the index with an Item Response Theory (IRT) model. This approach was initially developed in the field of educational testing. Teachers try to measure students’ underlying, or “latent,” ability in some subject like math or biology. A simple way to do this would be to add up all of the correct responses to each test question. However, some questions are harder to answer than others. IRT allows one to estimate how difficult questions are and incorporate this information into an estimation of how able students are in the subject. We extend this logic to measure countries’ transparency levels. In place of a dataset of students’ correct/incorrect answers to questions on a test, we created a dataset of whether a country reported key pieces of data about their financial systems to the IMF and World Bank in each year and then used IRT to estimate the country’s latent financial supervisory transparency.

FRT in EU Member States and other High Income Countries

How transparent are European Union member states relative to other countries? Among a sample of 68 high and middle income countries over the period 1990-2011, we found that most countries have FRT scores close to zero. This means that they generally report items that are estimated to be easy to report, but do not report the more difficult items. A country moves away from zero either when it reports the more difficult items, which were estimated to be related largely to non-bank financial institution data (thereby achieving higher positive scores), or when they do not report the easy items (thereby earning negative scores).

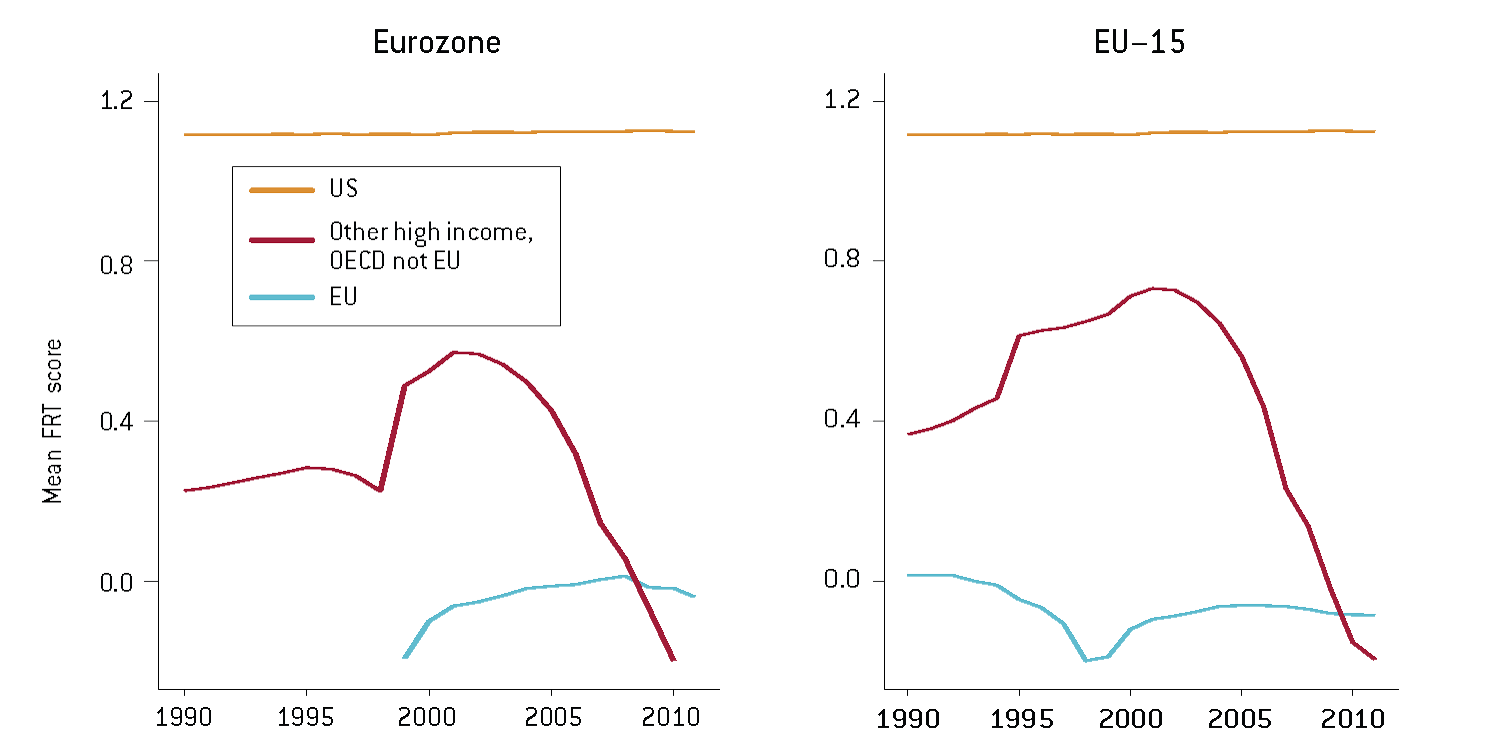

The most relevant comparison for EU member states is the group of other high income economies in the OECD. Figure 1 compares the mean FRT Scores for Eurozone and EU-15 countries to those of other high income OECD members in the sample. Another large banking union, the United States, is also highlighted. Figure 1 illustrates that European Union member states are less transparent in reporting national aggregate data to the IMF and World Bank than their high-income peers. In fact, almost all EU member states have scores close to zero for much of the sample period. Through the mid-2000s, non-EU high income countries had on average more international supervisory data transparency than either Eurozone or EU-15 members.

The reason for the discrepancy is that few European countries report important “difficult” items namely non-bank financial institution data–e.g. data on assets from insurance companies, state-owned non-bank institutions, postal savings banks, investment banks, and offshore financial institutions[1]–over the entire sample period. Since about 2004, many Eurozone member-states have also stopped reporting another basic indicator: the bank lending to deposit spread. Reporting in other high income OECD countries only declined towards the EU member’s low average level during the height of the global financial crisis. The US is notable for both its relatively high transparency level and its consistency in reporting data, even during the financial crisis. No EU country ever achieved a median transparency score at or above the US’ level,[2]

Overall European countries have a relatively low level of transparency compared to other high income OECD countries. This is especially true when we compare EU members to another large banking union: the United States.

Figure 1: Mean FRT Scores for EU and Eurozone Members vs. All other High Income Countries

Enhancing Transparency in Europe

In order to improve the efficiency and democratic accountability of the European banking and capital markets unions, it would be useful to institutionalise the reporting of financial system data to international institutions like the IMF and World Bank at the European level.

We propose that the European Central Bank, European Banking Authority, the European Insurance and Occupational Pensions Authority, and the European Securities and Markets Authority–which together have supervisory powers and access to the relevant data on currently underreported quantities–take a larger and more active role in coordinating the reporting of supervisory data to the IMF and World Bank. Especially within the Eurozone, this would have the benefit of improving the Eurozone’s relationships and representation with the IMF. While these are European-level institutions, they should report the national-level data in order to ensure greater supervisory transparency for the Eurozone as a whole, as well as for its component member-states. Even though this type of data is not directly covered under the capital markets union, such reporting is certainly in the spirit of creating a more efficient financial sector.

Finally, and relatedly, one might ask if the problem is not with the supervisor releasing the data but with the relevant institutions that are not reporting it. That is, a supervisor cannot report data it does not have. As we discussed in past work (Gandrud and Hallerberg 2015), there is also an issue of regulatory transparency for individual banks. In the United States, where this type of transparency is high, banks fall under the US common deposit insurance scheme only if they report reliable data that the supervisor then makes public. Given the initial moves towards a common deposit insurance scheme in the European banking union, a similar requirement should be part of any extension of deposit insurance across borders, be it as a common pool or as linked pools of different national programmes.

[1] The only EU member states to report this item in the sample period are:

- Cyprus (2004-2007)

- Ireland (1990-1998)

- Netherlands (1990-1998)

- Sweden (1995-1999)

[2] The Netherlands had a score of 1.06 in 1991.

Republishing and referencing

Bruegel considers itself a public good and takes no institutional standpoint. Anyone is free to republish and/or quote this post without prior consent. Please provide a full reference, clearly stating Bruegel and the relevant author as the source, and include a prominent hyperlink to the original post.