Blog Post

How loose is China’s monetary policy?

On the contrary, among the major central banks, the PBC appears to have tightened the most since the global financial crisis, on the basis of both ex-post real policy rate and real effective exchange rate.

On the contrary, among the major central banks, the PBC appears to have tightened the most since the global financial crisis, on the basis of both ex-post real policy rate and real effective exchange rate.

In my recent blog, I discussed the debate over whether China’s monetary policy was excessively restrictive before the latest monetary easing. There, the debate was framed mostly from a domestic perspective, using a closed-economy version of the Taylor rule. This is in part justified on the ground that China’s capital controls still bind (See Ma and McCauley, 2007). Of course, China, known for its so-called ‘export-led’ growth model, hardly qualifies as a closed economy.

Moreover, Reserve Bank of India Governor Raghuram Rajan recently raised concerns about the international spillovers from “competitive monetary easing” among major central banks (See Rajan 2014). Rajan’s concerns make sense to me. By definition, the world is a closed economy and often dominated by major central banks who behave more like price setters than price takers. ‘Price’ in this context used to be short rate only, but since the global financial crisis has also included the fuller yield curve. Thus strong policy measures taken by major central banks ought to produce global repercussions.

This in turn poses the interesting question of how loose or tight China’s monetary policy might be relative to its major international peers. In particular, how does the PBC fare in the global race towards monetary accommodation since the global financial crisis in 2007? This is a question of global perspective, and there is no better benchmark than the club of the central banks that issue the four basket currencies of the Special Drawing Rights (SDRs): the US Federal Reserve (Fed), the European Central Band (ECB), the Bank of Japan (BoJ) and the Bank of England (BoE).

We know that most of these major central banks have substantially expanded their balance sheets in recent years. We also know that China experienced a massive credit binge since 2007. Its total credit to the non-financial private sector relative to GDP, including the fast expanding shadow banking sector, rose from 120 percent in 2007 to 180 percent in 2013. This contrasts with the ‘creditless recovery’ in the euro area (see Darvas, 2013).

However, to better gauge the relative monetary policy stances of these five major central banks, we need to compare apples to apples directly. One way is to look at two key price indicators: the real policy rate and the real effective exchange rate. First, the Taylor rule suggests that the real policy rate should relate to the deviation of actual from target inflation, the output gap and the short-term rate consistent with full employment. Second, the best measure of global currency strength is the real effective exchange rate. Third, these two price indictors interrelate and define the two core aspects of an economy’s monetary condition.

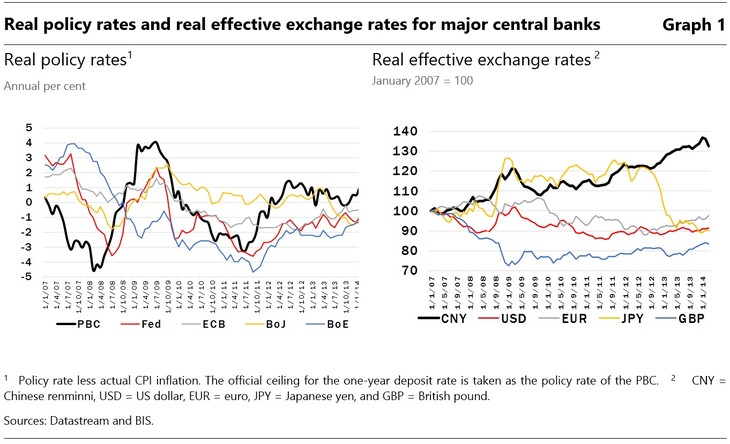

Both the real policy and effective exchange rates used here are ex post. I define the real policy rate as the policy rate less concurrent CPI inflation. I also use the CPI-based real effective exchange rate. To examine the relative policy tightness of the big five central banks since the global financial crisis, I focus on the period between January 2007 and March 2014. The following graph tells the story:

Currently, all five major central banks except the PBC have negative real policy rates (left panel, Graph 1). Indeed, the four SDR central banks have aggressively pursued real negative interest rates. For the past five years, the US Fed, ECB and BoE all have persistently maintained negative real policy rates. Even the BoJ has managed to push its real policy rate into negative territory since 2013, as inflation has risen in the wake of its “Quantitative and Qualitative Easing”. Also notice that lately, the ECB’s real policy rate has been edging towards positive territory under the disinflationary pressure across the euro area (See Darvas et al, 2014). In any case, China now has the highest real policy rates among the five major central banks.

Of course, unconventional monetary policy goes one step further to influence the long end of the yield curve. The exchange rates of the big four SDR currencies are then indirectly influenced. In China’s case, the PBC directly manages both its interest rate and exchange rate, given the binding capital controls. Either way, the real effective exchange rate serves to highlight another important aspect of monetary policy.

The real effective exchange rate reveals that among these big five currencies, only the Chinese renminbi (CNY) has shown sizable appreciation (35 percent) since 2007 (right panel, Graph 1). Meanwhile, the other four SDR member currencies (the dollar, euro, yen and sterling) have registered 5 percent to 15 percent real effective depreciation. Note that the yen appreciated noticeably between 2007 and 2012 until Abenomics, but has since weakened by 30 percent from its peak in 2011. Also, lately, the euro has strengthened, possibly adding to the disinflationary pressure in the euro area.

Therefore, both the real policy rate and the real effective exchange rate indicate that the PBC has maintained the tightest policy among the big five central banks following the global financial crisis. The BoE appears to have pursued the most aggressive monetary easing to date.

What are the implications of a meaningful monetary tightening by the PBC relative to the four SDR central banks? There are at least three as far as China is concerned.

First, China has borne the brunt of the global demand and current-account rebalancing over the past seven years. This tighter monetary policy added significant deflationary headwind to a slowing Chinese economy experiencing both a shrinking current-account surplus and weakening domestic demand.

Second, this deflationary headwind was only partially countered by a massive credit binge that should be viewed more as a quasi-fiscal stimulus than a proper monetary expansion. China’s relative monetary tightening thus might actually aggravate its domestic imbalance, because much of this fiscal stimulus funded hasty investment projects.

Third, China’s relatively tight monetary policy likely offset some international spillovers from the competitive monetary easing implemented by other major central banks, by not adding to the massive global monetary stimulus. This should in turn help dampen the volatility of those highly procyclical capital flows facing emerging markets and ease the competitive devaluation pressure globally.

Assistance by Giulio Mazzolini and Noah Garcia is gratefully acknowledged.

Read more on China

China seeking to cash in on Europe’s crises

China’s financial liberalisation: interest rate deregulation or currency flexibility first?

Review: The China slowdown effect

Financial openness of China and India: Implications for capital account liberalisation

Developing an underlying inflation gauge for China

Are financial conditions in China too lax or too stringent?

How tight is China’s monetary policy?

The Dragon awakes: Is Chinese competition policy a cause for concern?

China gingerly taking the capital account liberalisation path

Republishing and referencing

Bruegel considers itself a public good and takes no institutional standpoint. Anyone is free to republish and/or quote this post without prior consent. Please provide a full reference, clearly stating Bruegel and the relevant author as the source, and include a prominent hyperlink to the original post.