Blog Post

Negative deposit rates: The Danish experience

A look at the Danish experience by assessing the impacts of the negative deposit rate on the exchange rate and on financial markets in Denmark

See also policy contribution ‘Addressing weak inflation: The European Central Bank’s shopping list‘, interactive map ‘Debt & inflation‘ and comment ‘Negative ECB deposit rate: But what next?’.

Danmarks Nationalbank (DNB), the Danish central bank, applied a negative deposit rate for the deposits that banks placed with the DNB between 5 July 2012 and 24 April 2014. Such a negative deposit rate was quite an extraordinary measure, since it implied that banks pay interest for placing a deposit at the central bank. In this post I look at the Danish experience by assessing the impacts of the negative deposit rate on the exchange rate and on financial markets in Denmark. (See the policy contribution by my Bruegel colleagues in which they assessed, among others, the possible impacts of a negative central bank deposit rate in the euro area.)

Denmark’s monetary policy

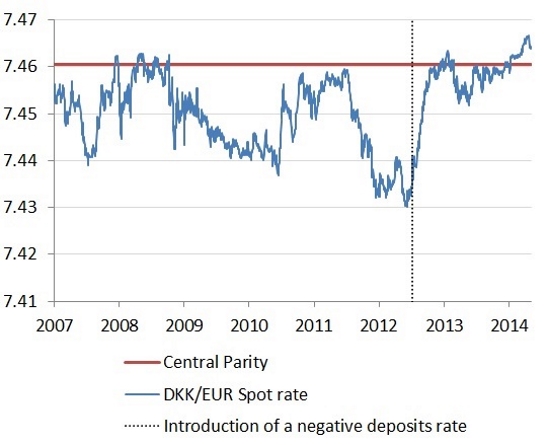

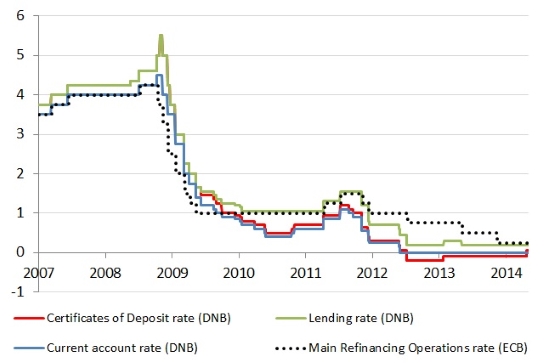

The objective of Denmark’s monetary policy is to keep the krone stable vis-à-vis the euro, given that Denmark is part of the European Exchange Rate Mechanism (ERM II) since 1999. While the standard with of the ERM II band is +/-15%, Denmark has a narrower fluctuation band in ERM II of +/- 2.25 % and does not even use the full width of this band but keeps the krone rate closer to the central parity (see Figure 1). In order to influence the krone rate, the DNB sets the monetary policy interest rates (various lending and deposit rates for banks) and intervenes in the foreign exchange market by buying/selling euros. When the foreign-exchange market is calm, the Danmarks Nationalbank usually adjusts its interest rates in line with the adjustments of the monetary policy interest rates of the European Central Bank (see Figure 2). However, when there is a sustained upward or downward pressure on the krone e.g. due to a sustained inflow or outflow of foreign currency, the DNB unilaterally changes its interest rates to stabilise the krone and intervenes in the foreign exchange market.

Figure 1, The Danish krone exchange rate against the euro

Source: Datastream. Note: The central parity is 7.4604 kroner per euro and the edges of the +/-2.25% fluctutation band are 7.26 and 7.63 kroner per euro. A decline in the value implies an appreciation of the Danish krone.

Figure 2, Danish central bank interest rates and the European Central Bank’s main refinancing rate (percent per year)

Source: Datastream, ECB; Note: The DNB has two deposit facilities for banks: a so-called current account, at which banks can place only a limited amount of money overnight, and a so-called certificates of deposit, which has a maturity of 7-days. The lending rate is the rate at which banks can borrow liquidity from the DNB. The DNB also has a discount rate (not shown in the graph), which acts as a signal rate and does not refer directly to monetary policy facilities.

The implementation of negative deposit rates

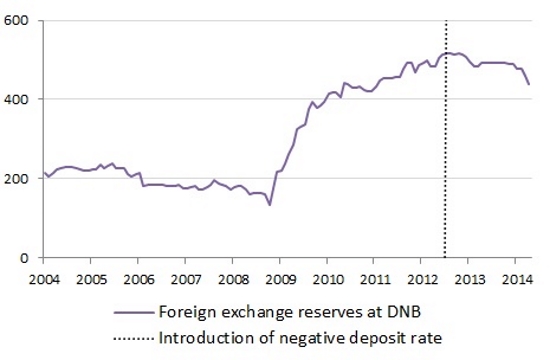

Interestingly, in the height of the global financial crisis, after the collapse of Lehman Brothers in September 2008, the DNB had to raise its interest rate (and thereby widen the spread relative to the main refinancing rate of the European Central Bank) to protect the exchange rate of the Danish krone. However, the direction of the pressure on the exchange rate reversed quickly and few months later capital inflows to Denmark intensified, which was reflected in a doubling of the foreign exchange reserves of the DNB. From mid-2011 to mid-2012 safe-haven flows intensified, as investors used the Danish krone to hedge against an eventual break-up of the euro (Danmarks Nationalbank, 2013, pushing the DKK/EUR exchange rate to a stronger value (Figure 2). As a response, Danmarks Nationalbank cut its rate further and intervened heavily in the foreign exchange market, which led to a substantial increase in foreign exchange reserves of the DNB (Figure 3).

Figure 3, Foreign-exchange reserves of Danmarks Nationalbank, DKK bn

Source: DNB

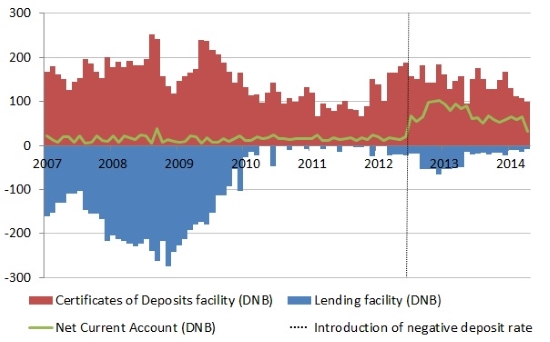

After a long period of interventions in the foreign exchange market to stop the sharp appreciation of the Danish krone, the DNB decided in July 2012 to introduce a negative deposit rate of minus 0.2 percent per year on banks deposits at the DNB, while it kept the zero interest rate on the current account of banks (Danmarks Nationalbank, 2012). The negative deposit rate meant that banks had to pay interest for placing a deposit at the central bank. To alleviate the pressure on banks, the DNB at the same time increased the limit for banks to hold liquidity at the DNB’s current account from DKK 23.14bn to DKK 69.70bn. This enhanced the scope and incentive for the banking sector to place liquidity at the DNB to manage daily liquidity fluctuations, without resorting to the money markets. The Danish banks had a positive net position with the central bank (see Figure 4), which increased due to DNB’s purchases in the foreign-exchange market and the increased foreign-exchange reserves. Hence, deposit rates played a much more important role in stirring money market rates compared to the central bank’s rate on lending and thus also the major tool to maintain exchange rate stability versus the euro. With the introduction of the negative deposit rate, the volume of liquidity held in the certificates of deposits facility slightly decreased, while the liquidity parked in the DNB’s current account went up (for which a zero interest rate continued to apply).

Figure 4, lending and deposits at the Danish National Bank, in DKK bn

Source: DNB

Impact on the foreign exchange market and capital inflows

The most direct effect of lowering the deposit rate below zero was the depreciation of exchange rate, which reached the central parity shortly. Hence, the introduction of negative interest rates can be seen as a successful experience in the Danish case, which aimed at restoring the central parity of the EUR/DKK exchange rate. Also, the developments of foreign exchange reserves held by the central bank suggest that capital inflows have stopped from mid-2012 onwards (see Figure 3).

Impacts on market interest rates and money market activities

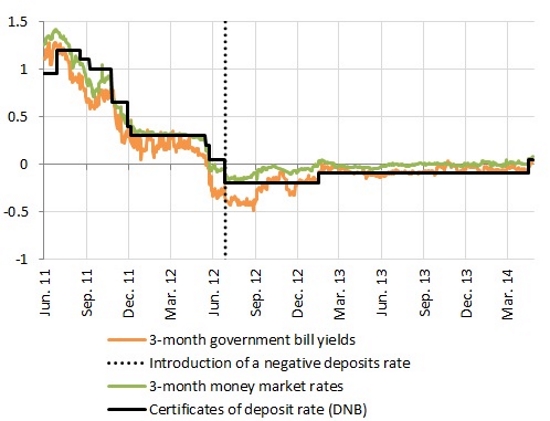

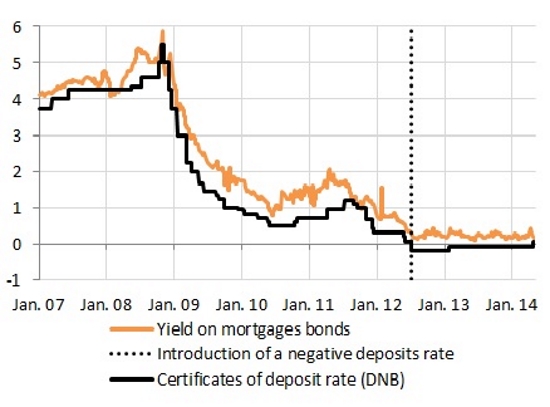

Panel A of Figure 5 shows that Danish T-bills were already trading with negative yields before DNB deposit rate cut below zero, and decreased somewhat further after the rate cut. Also, the yields on Danish mortgage bonds declined when negative interest rates were introduced (Figure 5, Panel B). This might suggest a slight portfolio rebalancing effect, as banks resorted to other liquid markets (see Figure 5, Panel A and B).

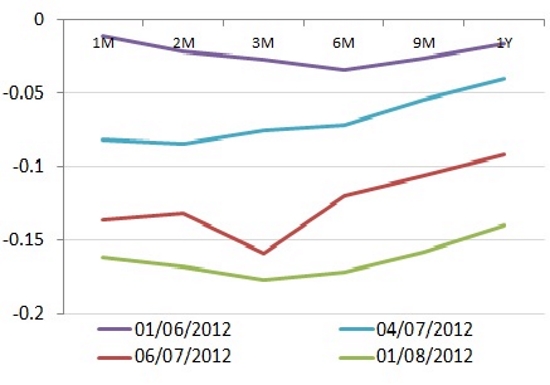

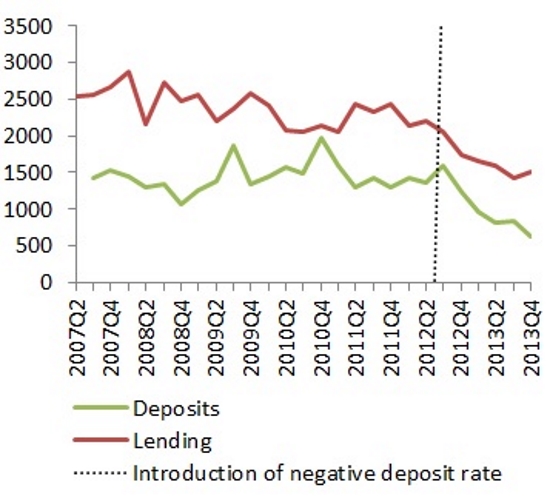

The negative deposit rate also influenced Danish money market activities. Panel C of Figure 4 shows a fall in the whole term-structure of money market rates up to 1 year, comparing the DKK Overnight Index Swap (OIS) forward curve before the introduction of negative deposit rates (4/7/12) to the forward curve a day after the announcement (6/7/12), as well as one month after (1/8/12). This shows that money-market rates for all maturities up to one year were already negative before the DNB rate cut on the 5th of July 2012. The pass-through to money market rates was immediate, though incomplete, because money market rates did not decline as much as the DNB deposit rate. Concerning the volumes exchanged, Panel D in Figure 4 shows that the volume in the overnight money market declined somewhat in the period from 2011Q4 to 2012Q4, accelerating a trend which started already in 2010.

Figure 5, Danish interest rates and money market volumes

Panel A – Danish T-bills yields (in %)

Panel B – Danish mortgage bond yields (in %)

Panel C – Money market terms structure (in %)

Panel D – bank’s lending and deposits in the overnight money market (in bn DKK)

Source: DNB, Datastream

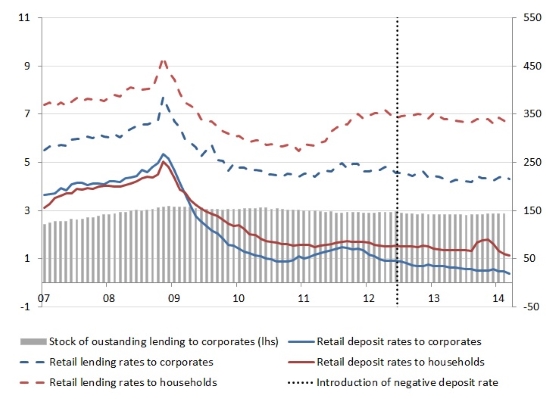

The concern that banks, reluctant to pass the cut on to their own depositors, might be tempted to increase lending rates in order to offset the decline in their profitability did not materialize in Denmark. Figure 6 shows that the pass-through to retail lending rates was minimal, with rates to corporates and households being more-or-less stable since the deposit rate cut in 2012. Lending activity from banks to the corporate sector decreased slightly, from 144.54 bn in 2012 to 141.7 bn in 2013 (See Figure 6).

Figure 6, Danish retail rates for households and corporates (in %) and lending volumes to the corporate sector (in bn of EUR)

Source: ECB, DNB

Abandoning the negative deposit rate

With the gradual reduction of the stresses in euro area financial markets from the second half of 2012, capital outflows from the euro area in search for safe havens have also likely reduced. This has paved the way for the elimination of the negative DNB deposit rate. Already in January 2013, the DNB increased the deposit rate from -0.2 to -0.1 %, following interventions in the foreign exchange market to mitigate the strengthening of the DKK/EUR rate due to higher euro money market rates (see http://www.fxstreet.com/analysis/flash-comment/2013/02/04/). In April 2014, the DNB ended the exceptional period of negative rates by setting its rate on certificates of deposits at +0.05%. Also, it reduced the ceiling put on the current account for monetary counterparties to 38.5 bn DKK from 67.4 bn DKK. This decision was taken on the back of declining excess liquidity in the euro area, which pushed up short term rates in the euro area (see Silvia Merler’s blog post “shrinking times” /nc/blog/detail/article/1311-shrinking-times/). These are now higher than the equivalent Danish rates, a fact which has tended to weaken the Danish krone (see press release).

Summary

Overall, the negative deposit rate introduced by Danmarks Nationalbank in July 2012 was successful in limiting capital inflows and helped to push back the exchange rate of the Danish krone toward the central parity. Therefore, the adoption of the negative deposit rate was helpful in reaching the major objectives of its introduction. Moreover, while money market rates and treasury bill yields were already negative before the introduction of the negative DNB rate, after its introduction, these yields fell slightly further and yields on mortgage bonds also stabilised at a very low level. The evidence suggests that the rate cut did not lead to changes in retail interest rates, nor an increase in bank lending. With the normalisation of euro-area financial markets, the DNB could increase the deposit rate from -0.2 percent to -0.1 percent in January 2013 and to +0.05 percent in April 2014.

***

References:

Danmarks Nationalbank (2012) ‘Monetary Review’, 3rd Quarter

Danmarks Nationalbank (2014) ‘Fixed exchange rate policy in Denmark’, Monetary Review, 1st Quarter

Danmarks Nationalbank (2009) ‘Monetary Policy in Denmark’

Rasmussen Arne Lohmann (2013) ’Negative deposit rates, the Danish experience’, Danske Bank, November

Jan Størup Nielsen and Anders Skytte Aalund (2013) “Denmark Update, “Negative interest rates – the Danish experience”, Nordea Research, April

Republishing and referencing

Bruegel considers itself a public good and takes no institutional standpoint. Anyone is free to republish and/or quote this post without prior consent. Please provide a full reference, clearly stating Bruegel and the relevant author as the source, and include a prominent hyperlink to the original post.