Blog Post

The euro area’s need for stabilization in historical perspective

It is not unusual that some European countries register strong growth rates and others less so. Yet, significant divergence in output is historically associated with dramatic events (or crises). This implies that a euro area budget used for stabilization will end up being activated only a few times. Moreover, there is no historical record of core Europe marching above and the periphery below potential. This makes it unrealistic to conceive of a euro area budget that transfers resources on the spot from badly hit to just moderately hit countries. Some institutional engineering would be necessary.

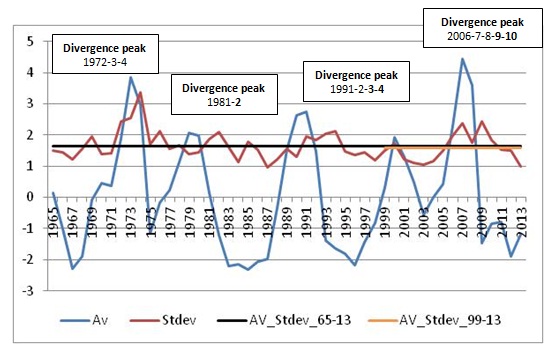

Figure 1: The incidence of large asymmetric shocks over time

Source: Bruegel based on AMECO database.

The debate on the need to introduce a euro area budget (or an EU-wide risk sharing mechanism) stems from the realization that all potential stabilization tools have so far not been very useful or even damaging to countries (see debate on fiscal austerity in bad times), and that an EU stabilization fund may indeed serve to smoothen cyclical fluctuations that affect members of the monetary union in opposite directions (or asymmetric shocks)1.

How often does it happen that countries pertaining to the same economic area are in dramatically different business cycle positions? How severe is the divergence? How persistent is it?

Figure 1 shows the standard deviation in the output gap across eleven countries that entered the monetary union between 1999 and 2001 (Austria, Belgium, France, Germany, Greece, Ireland, Italy, Luxembourg, Netherlands, Portugal, and Spain). The data go back to 1965 at a time when Ireland, Greece, Portugal and Spain were not even members of the European Union but the figures still give an indication of European output trends and allow for comparison with recent crisis times2.

We juxtapose the standard deviation in each year with the average standard deviation in output gaps across the entire period from 1965 to 2013 (forecasts for 2012 and 2013). We also include the average of the period following the inception of the EMU regime to control for the fact that the single currency may automatically (or endogenously) produce business cycle synchronization, thereby reducing average volatility.

Data in Figure 1 confirm the following: i) that some countries go through hard times and other through better times in the same period is a standard feature of the European economy but above-average output divergence is something that is historically associated with dramatic events (ie currency crisis in the early 1970s, recession in the early 1980s, currency crisis in the early 1990s and the Euro area crisis); ii) more recent divergence peaks have been generally more persistent, a possible explanation being that deeper economic integration enhances the international propagation of shocks across partner countries, which creates further (pro-cylical) feedback effects.

Output divergences do not per se justify having a risk-sharing mechanism that transfers resources from least deviating to most deviating countries. If all countries are below potential but to different extents, the EU stabilization fund would just transfer money from less poor to poorer countries.

In Figure 1 we also plot the average output gap to bring to light periods in which a high standard deviation is just the result of the fact that countries are facing more or less severe hard times, whilst but all being in recession3. By looking simultaneously at standard deviation and averages, it appears that large asymmetric shocks have been historically associated with boom bust cycles, with first all countries growing but to different extents and then all countries stuck below potential but to different degrees. In other words, euro area countries tend to occupy the same territory (whether positive or negative).

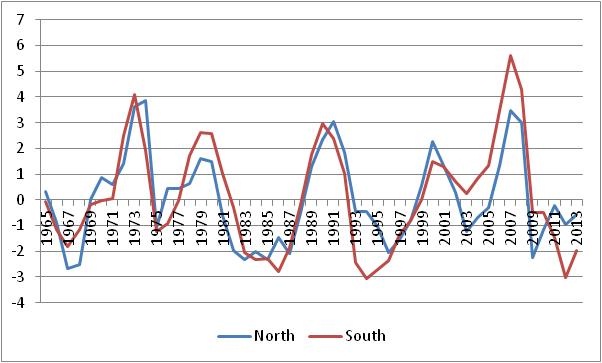

To make this clearer, Figure 2 describes the average output gap over time distinguishing between two areas, the North and the South of the euro area. There is not a point in time when the average output gap in one area is negative and the other positive, which is the only situation where transfers would be politically acceptable since they move from booming to busting economies.

Figure 2: Average output gap in the North (AUT, BE, DE, FR, LUX) vs South (EL, ES, IE, IT, PT)

Source: Bruegel based on AMECO database

The patterns described here provide insights into the debate about if/how to design a euro zone’s fiscal capacity to cushion asymmetric shocks:

- a rigorous enforcement of the Excessive Imbalance Procedure (EIP) and thus “early treatment” of boom bust cycles reduces the need for a European fiscal capacity when the bust occurs;

- the EU should extract an interest-bearing deposit rather than a proper fine from countries that fail to solve their macroeconomic imbalances; the cash should be paid into a fund, which provides transfers when the bust occurs, anywhere in the monetary union and in proportion to the severity of the bust;

- the latter mechanism is unlikely to create moral hazard, as governments will continue to regard the interest-bearing deposit as a stigma;

- alternatively, the new fiscal capacity should be allowed to borrow on capital markets and may only be balanced over five-year periods and not less, as this is the average duration of EU-wide below-potential periods (see Figure 1);

- a functional equivalent to an EU-wide risk-sharing mechanism is fiscal expansion in all countries during recessions, which would imply that all euro area countries are temporarily allowed to have nominal deficits above 3% of GDP4;

- assuming the shock is on the supply side, stronger government consumption may not be sufficient to offset it; in this case, deficits above 3% of GDP should be allowed but anything above 3% should just go towards financing government investment (ie it would qualify as a state-contingent temporary “golden rule”).

The debate remains open.

1. For a discussion on why the euro area needs a shock-absorbing budget, se Wolff G.B., A Budget for Europe’s Monetary Union, Bruegel Policy Contribution, December 2012.

2. By using the output gap as a measure of economic activity we are not implying that this is best indicator. In fact, there may be others that provide more reliable real-time information (eg labour market indicators), but the latter would be typically pro-cyclical so that our general assessment of the size and duration of instability remains valid.

3. Data in bold refer to years during the divergence peak when the average output gap in the euro area is negative.

4. An earlier suggestion is in Marzinotto B. and Sapir A., Fiscal rules: timing is everything, Bruegel Policy Brief, September 2012.

Republishing and referencing

Bruegel considers itself a public good and takes no institutional standpoint. Anyone is free to republish and/or quote this post without prior consent. Please provide a full reference, clearly stating Bruegel and the relevant author as the source, and include a prominent hyperlink to the original post.