Blog Post

The World in 2020

For Europe, and within it, the EU and especially for those inside EMU, the need to change both their policy framework is particularly clear, not least as they hold many of the important keys for better global governance.

In a recently published paper, we showed that the world is going through an unprecedented shift of economic growth distribution and trade patterns. We also extrapolate what the world trade situation will look like by 2020 if this continues. The situation is hugely influenced and complicated further by the development of China and its changing economy, which is likely to grow at a slower rate in this decade than in the last. China will find it more difficult to export as much and will import more. Nonetheless the Chinese share of global GDP and trade will rise further. Other countries from the so called emerging world will have a smaller role in this changing landscape but a non-trivial one. All of this surely means the need for a significant shift in world economic governance is becoming pressing.

For Europe, and within it, the EU and especially for those inside EMU, the need to change both their policy framework is particularly clear, not least as they hold many of the important keys for better global governance.

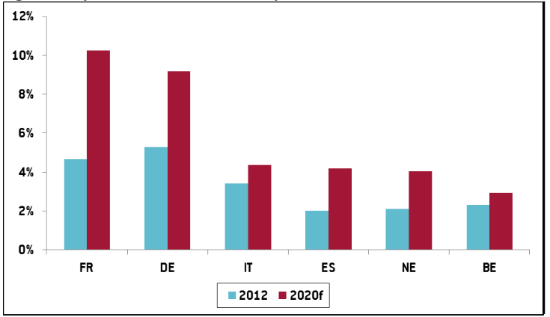

In the paper, we show that by 2020, China will probably be Germany’s number one export market. China will be close behind Germany as France’s next most important export market (a finding that might surprise some people even more than the German export shift). Italy, the euro area’s third largest economy, will not see its export share to China rising quite as much, but it will be exporting more to so-called emerging/developing markets than its developed market counterparts. This means that the euro area’s 3 largest economies are going to be thinking more and more about their trade relationships with countries outside the euro area.

Figure 1. Exports to China, % of total exports

Source: O’Neill and Terzi (2014).

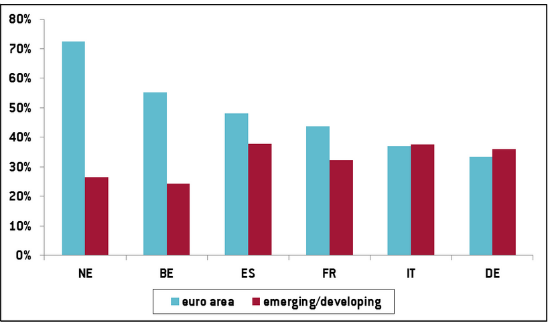

Our findings suggest that this same pattern will not be repeated for all euro area members, and for some, their own exports to these larger European economies will remain very significant. This is an important finding also as otherwise, one could simply question whether the euro area will still satisfy the most basic of optimal currency area (OCA) criteria. In theory, an optimal currency area has strong economic basis when the OCA member countries are conducting most of their trade with each other. This was the main economic rationale behind EMU’s introduction and of course, one of the most bullish arguments of its supporters were that under a single currency, trade between member countries would flourish even more (see ‘One Market, One Money’, European Commission). What has happened 14 years on is that, trade has flourished even more outside the euro area.

Figure 2: Exports to euro area and emerging/developing markets in 2020 (forecast), % of total

Source: O’Neill and Terzi (2014).

In addition to these unexpected patterns of trade, of course, most European economies continue to see their share of global GDP decline as many other parts of the world grow faster. Despite these realities, global governance is only shifting in the appropriate direction at a snail’s pace. At the discussion surrounding the launch of our paper, the IMF pointed out that in 2010, it had been agreed that the respective shares and voting rights for the IMF should change based on criteria determined by 2005 relative economic and financial positions. These criteria included, among others, the size of GDP and performance in trade. As a result, the share of China would be rising to 3rd if implemented. However, these agreements are yet to be implemented and in fact, the US Congress in January passed on an opportunity to vote in favour of the IMF proposed changes. In any case, these were based on 2005 criteria which is now 8 years away. Today, China is two times the size of Japan following the release of final year GDP data, yet the proposal yet to be ratified suggests a share for China still behind Japan.

China is also now bigger than the GDP of France, Germany and Italy combined, and despite some disappointments with their own economic growth in the past couple of years, the BRIC countries combined GDP is bigger than that of the euro area. For Europe that still will hold a disproportionate share of IMF power even if the 2010 agreements ever get implemented (in which they lose 2 individual IMF seats), what would be the right thing to do?

The current problems surrounding Ukraine in many ways epitomize the slow and byzantine way Europe behaves about many issues. In public, European countries talk frequently about the rights and wrongs of how the Ukraine should be, but in the build up to this problem, they didn’t appear capable or willing to decide swiftly on tangible benefits for Ukraine or encourage it to accelerate any possible future as an EU member.

This is symptomatic of the broader issues facing the EU and euro area in particular in their policy development. As it relates to the euro area’s external credibility and achieving a better balance of global governance, as we argue in the paper, they can kill two (big) birds with one stone. They should stop representing themselves individually in the G7 (and G8) and encourage more shared representation in terms of IMF seats and voting rights. By doing the latter, they would also put more direct pressure on the US for their own intransigence in adopting change. By doing the former, they would not only allow for a more ideal G7 to become apparent- one in which China was sitting at the table- but it would send a huge message that the euro members were together as “ one” on monetary and fiscal , and broader economic matters for the future.

As necessary as these steps are, they are far from sufficient as they should be accompanied by other changes. There are perhaps three additional specific steps we would recommend for Europe to become more adaptable and less rigid in its approach to this fast changing world.

First, if the euro area is becoming more heterogeneous in terms of trade partners, the likelihood of an asymmetric macroeconomic shock and the risk that different European countries might find themselves at different points of the business cycle will be increasing. This, in turn, will make the conduct of a single monetary policy more challenging. As such, mechanisms which allow to shore up against this risk will be needed. This will need to include some sort of fiscal transfer or macroeconomic stabilization mechanism (see Kennen, 1969), together with a more solid integration and supervision of the financial sector (see Sapir et al., 2013).

If this contention is right, it could be claimed that the euro area has been moving steps in the right direction as part

of its crisis management strategy, given this included a tighter coordination of fiscal policies from the centre, the establishment of a common lending facility (European Stability Mechanism), and a move toward the creation of a banking union. We would however warn against the strict rule-based approach that is prevailing among European policymakers. While obviously the euro area needs to have appropriate economic discipline, events of recent years have demonstrated that when stresses occur and pressures build, these criteria don’t stop countries from breaching them. Moreover, the more-or-less strict consensual basis on which the EU operates, characterized by eternal negotiations, countless summits, and a myriad of veto players does not cater for the fast-paced uncertain world in which we have moved. The original sin of EMU itself was its conception as a rigid structure, allowing for no way to deal swiftly and effectively with unforeseeable external (the Great Recession) or internal (asset bubbles and competitiveness losses) shocks. We would thus favour a stronger centralization of competencies, associated with discretionary powers to cope with a fast-paced changing world, and the necessary democratic legitimization that this new governance will need.

Finally, connected to this last point, we do realize that not all EU countries may be ready to give up crucial parts of their sovereignty, now or in the foreseeable future, and so should do EU policy-makers. A stronger, more flexible, EU might thus need to accept the idea of being permanently characterized by a varying geometry.

Republishing and referencing

Bruegel considers itself a public good and takes no institutional standpoint. Anyone is free to republish and/or quote this post without prior consent. Please provide a full reference, clearly stating Bruegel and the relevant author as the source, and include a prominent hyperlink to the original post.