Blog Post

Policy coordination failures in the euro area: not just an outcome, but by design

Discussions on the fiscal framework should aim to correct its procyclical nature with a view to promoting more cooperative outcomes.

The rationale behind the Maastricht fiscal criteria was to prevent excessive spending (driven by uncoordinated fiscal policies) in response to external shocks. Excessive spending would in turn put market pressure on those ‘undisciplined’ fiscal authorities and compromise the long-term stability of the monetary union.

In reality, fiscal policy was too loose during economic booms, when it ought to have aimed to build up buffers and too restrictive in recessions, when it ought to have cushioned shocks. Fiscal policy in the euro area on average has therefore been procyclical.

Additionally, monetary policy, through the European Central Bank (ECB), has had to do a lot more than envisaged in order to compensate for the fiscal inaction during recessions. Now at the zero-lower bound, the ECB has less room for manoeuvre by conventional means and has built up an unprecedented balance sheet position. We still need to understand what this means for the real economy, monetary policy effectiveness and the independence of the central bank.

We argue that the procyclical nature of fiscal policy in the euro area and the subsequent overuse of monetary policy are not just outcomes. Rather, they are a failure of the fiscal framework to recognise (even unintentionally) that there are strategic interactions that, if not appropriately accounted for, lead to such outcomes.

A setup that aimed to prevent negative spillovers produced a strategic environment where, in the face of a negative shock, all countries ended up being more restrictive than they ought to. This prolonged the recessionary period caused by the negative shock and forced monetary policy from its first best.

By contrast, explicit cooperation between fiscal authorities can help improve outcomes for all. Fiscal authorities will be playing a bigger role to address the shocks, without ignoring the negative externalities in place. Also, monetary policy will not be as active so that macroeconomics management achieves better outcomes. The non-cooperative versus cooperative outcomes comparison serves as a good way of contrasting the overall macro response in the financial crisis to that in the pandemic crisis in the EU.

The Maastricht criteria were never a good tool for fiscal coordination

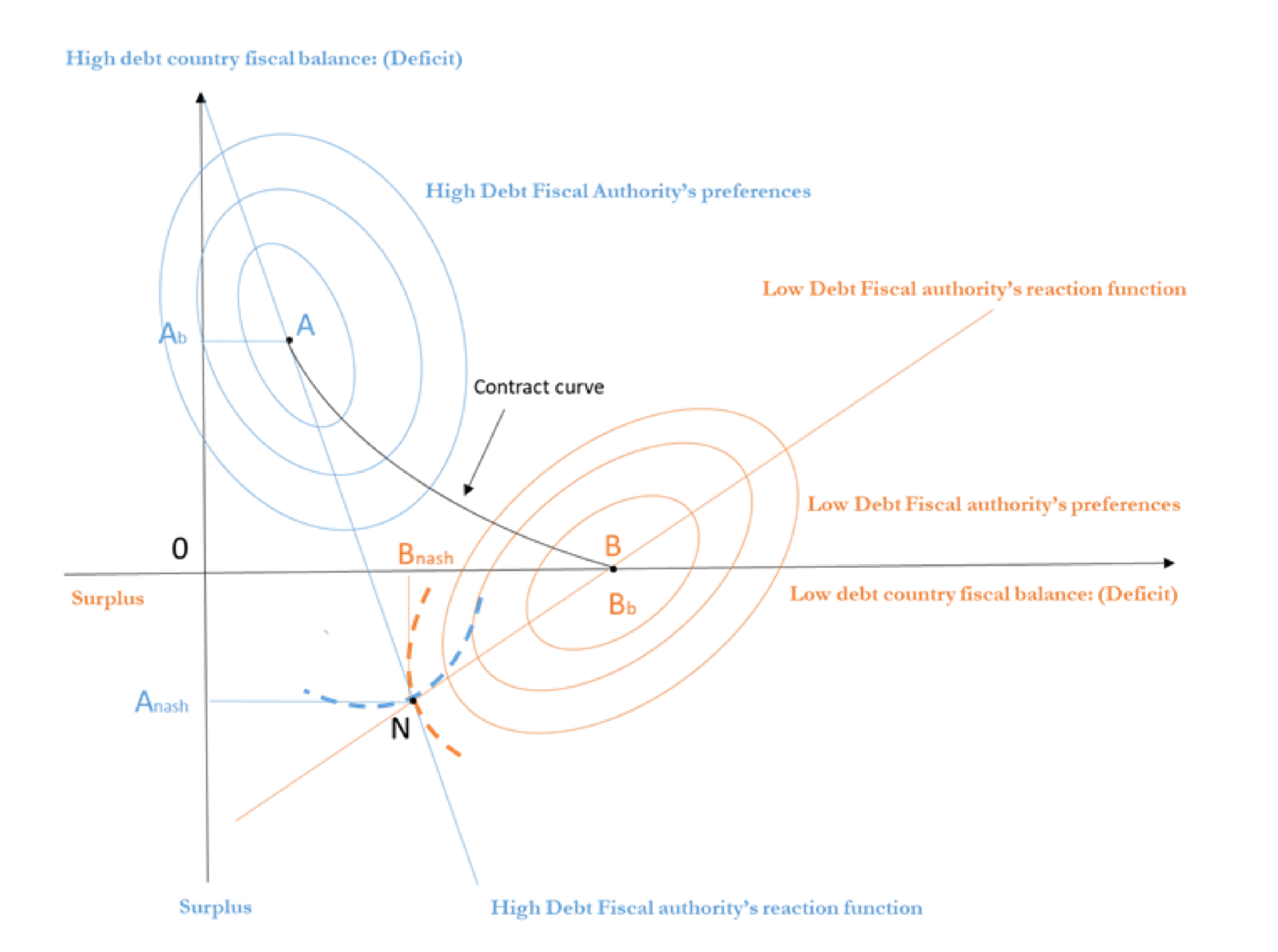

We describe this strategic interaction in the context of European monetary union based on the Hamada diagram (see here).

Consider the fiscal policy game between two countries in a monetary union, one with high levels of debt (country A) and one with low levels of debt (country B), that face a common negative shock. If the high debt country uses fiscal policy to counteract the shock, it will induce an increase in its spreads, which will damage not only itself but also the other country. This is the ‘fear’ behind the Maastricht criteria. On the other hand, when the low debt country uses its fiscal policy to counteract the shock, it benefits both itself as well as the other country, in a way that it would when countries are closely integrated.

The high debt country therefore imposes a negative externality on the Union when it uses its fiscal policy, whereas the low debt country imposes a positive one.

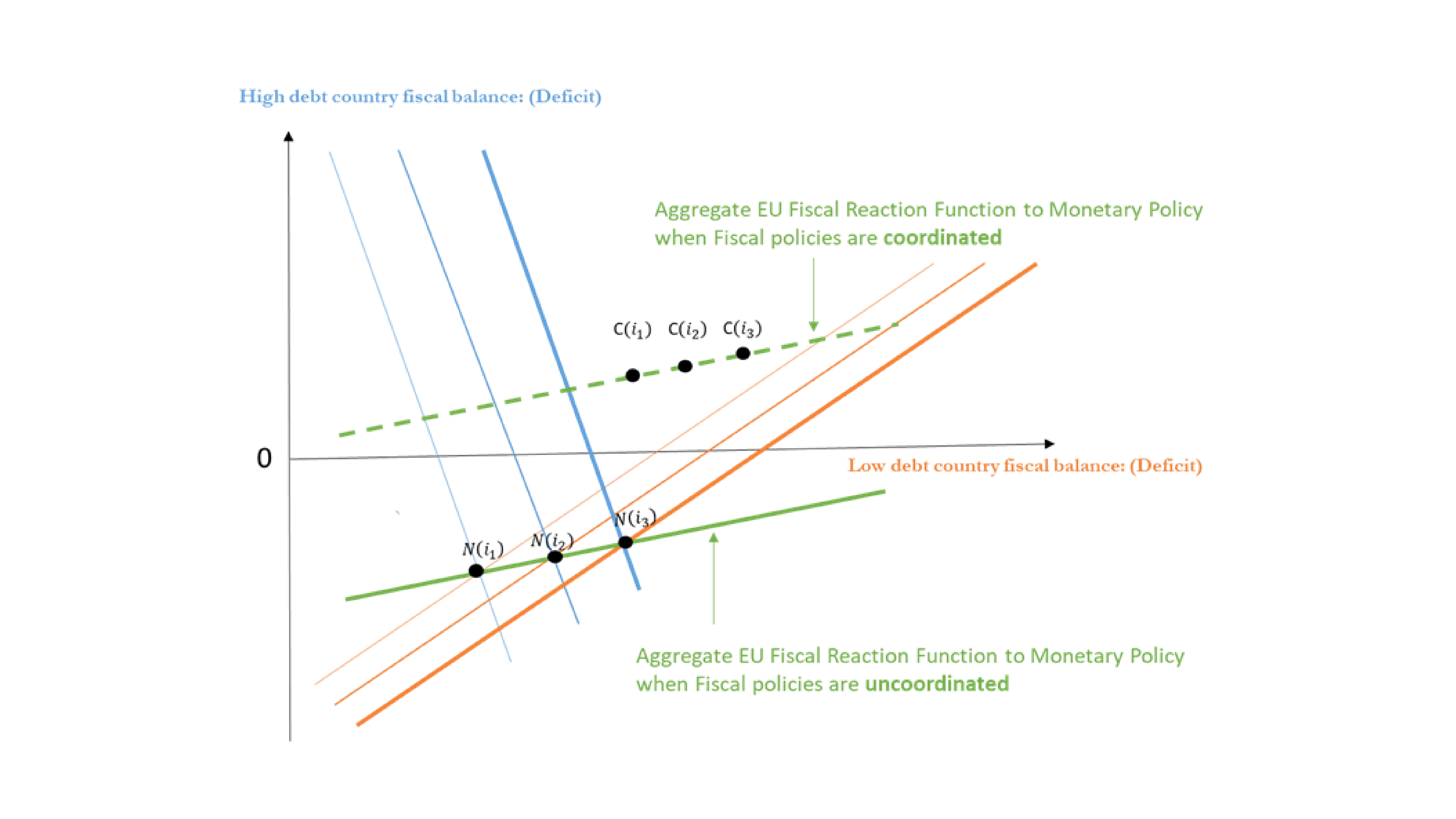

This asymmetry is reflected in the opposite slopes of their reaction functions (RFs) in Figure 1. Faced with a negative shock, the high debt country can benefit from the other country’s fiscal expansion and therefore reduce the pressure on its own budget (negative slope RF). The low debt country on the other hand will have to respond with a stronger fiscal response to counteract the negative spill over effect of the high debt country (hence positive sloped RF).

Points A and B reflect the optimal response to the shock for the two countries, absent any strategic interaction. There is a deficit bias in the high debt country Ab and a preference for fiscal stability in the low debt country (ie it wants the high debt country to do nothing, so point B is on the x-axis at value Bb).

Point N reflects the uncooperative outcome, when both players have accounted for each other’s actions, the Nash equilibrium of this policy game. The overall fiscal response to the external shock is too small (Anash+Bnash), and certainly by comparison to the cumulative response of both countries absent of the strategic interaction (Ab+ Bb, identified at respective bliss points). The high debt country’s response to the shock is actually pro-cyclical, as it ends up having a surplus.

Figure 1: Uncoordinated fiscal policies lead to the wrong fiscal policy

This shows that in response to a negative shock, the absence of explicit fiscal coordination between the two countries leads to a response that is much less expansionary than would be optimal and even procyclical for the high debt country. This is the result of each country using fiscal policy independently, but within a framework where there are interdependencies.[1]

[1] If fiscal policy response is linear, such that its size is the same irrespective of whether the shock is positive or negative (and of course opposite in sign), then the picture is entirely symmetric across both axes, for a positive shock. Graph available upon request.

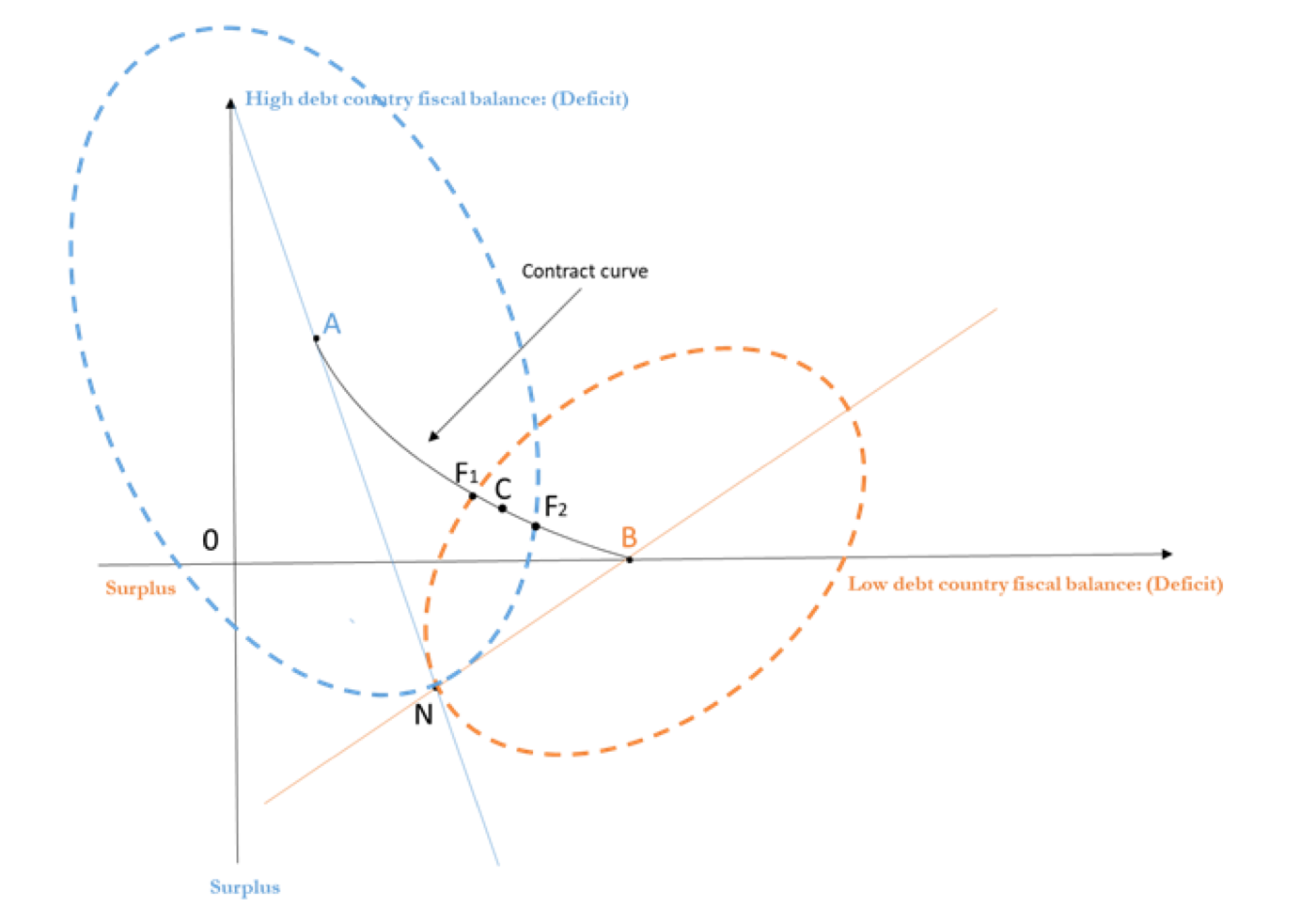

The contract curve tracks the pairs of fiscal responses when policies are coordinated (with different weights). There exists a coordinated fiscal policy response, like at point C in Figure 2, where both do better in welfare terms by comparison to Nash (indifference curves that go through C are closer to respective bliss points). The fiscal response of the high debt country is now counter-cyclical but not as big as it would have been, had the country not considered the negative spill overs it imposes.

Figure 2: If we coordinate, we can do better

Exactly where C will lie in the F1F2 part of the contract curve (where both countries do better than Nash) will depend on the bargaining power of the two players (and is known as the area of feasible policy bargain).

Monetary policy does most of the work

Next, we discuss how the lack of cooperation between the independent fiscal authorities affects monetary policy. The suboptimal fiscal policy outcome captured by the Nash equilibrium, point N in Figure 1, is conditional on monetary policy, in other words for a given interest rate level.

For a higher interest rate, both fiscal authorities would wish to have a more expansionary fiscal position (ie higher fiscal deficit) to counteract the contractionary effect coming from monetary policy. This means that both actors’ reaction functions move to the right as interest rates increase and so the respective Nash equilibria move north east, as shown in Figure 3. The collection of all Nash equilibria depicts the aggregate European fiscal reaction function to the common monetary policy.

Figure 3: Fiscal policy expands as monetary policy contracts

But we can also derive the equivalent aggregate EU fiscal reaction function to monetary policy when fiscal policies are coordinated, equivalent to the collection of all coordinated equilibria captured by the dashed green line. This line moves upwards and the coordinated equilibria move to the north-east of the Nash equilibria equivalent shown in Figure 2.

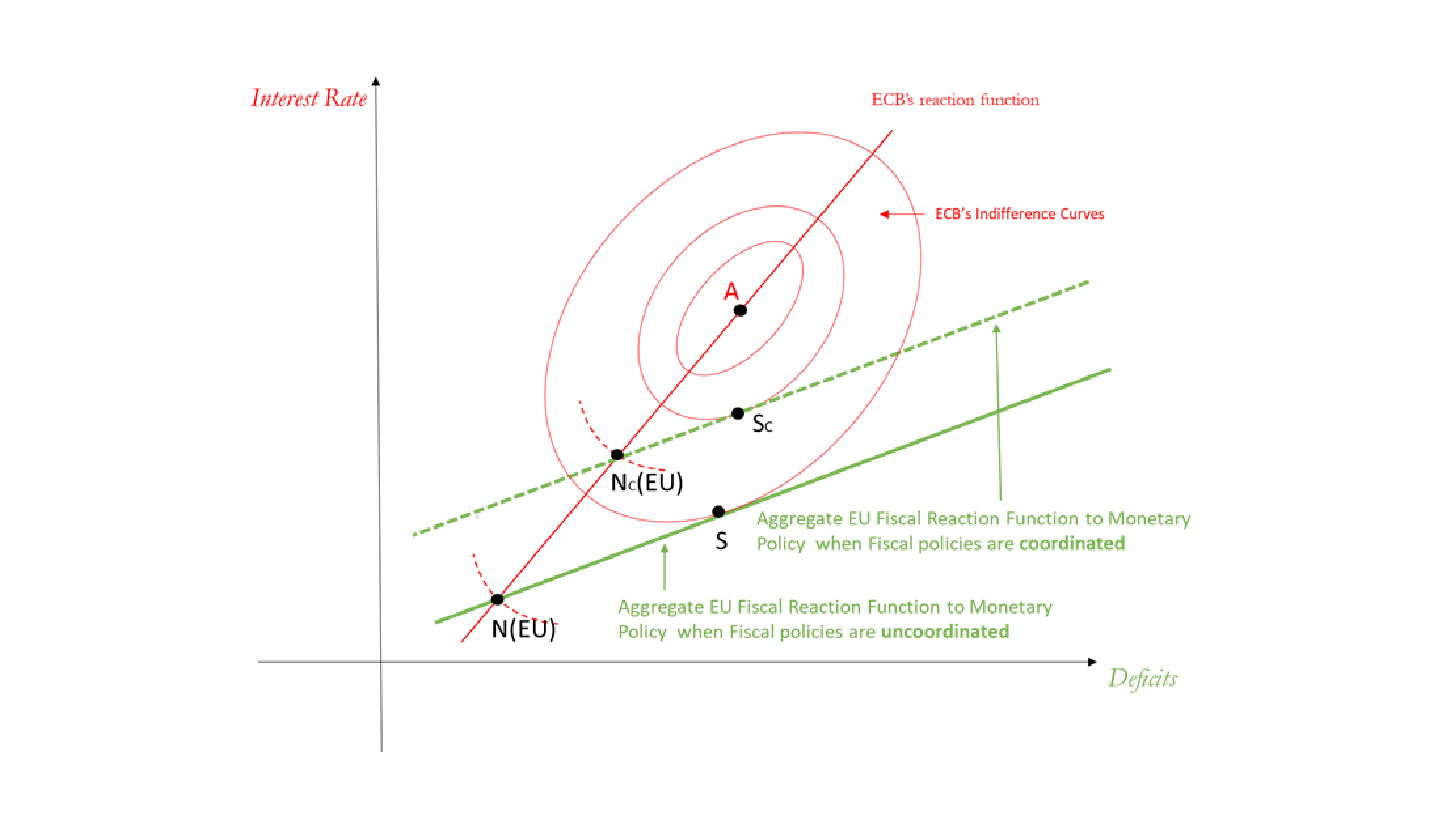

We can now consider the fiscal-monetary policy game in their respective instrument space, interest rate and deficits (Figure 4), for a given negative shock.

The ECB’s reaction function and the collective fiscal response are positively sloped. For any fiscal expansion, the ECB will increase the interest rate and similarly fiscal policy will be more expansionary the more contractionary monetary policy is.

Point A indicates the pair of values for the interest rate and deficit preferred by the ECB to deal with the shock (bliss point). In this graph we do not have a bliss point for the fiscal authorities as the fiscal reaction function is the set of equilibria for different levels of the interest rate. This also means that we cannot have a cooperative solution between the ECB and fiscal authorities (ie, we cannot have a contract curve) unless we first identify a cooperative solution among fiscal authorities that defines European wide fiscal preferences.

When monetary and fiscal policy are decided independently of each other, then the only credible outcome is the Nash equilibrium, point N(EU). We have shown that fiscal policy is underused in response to the shock, and it is now monetary policy that is having to be more expansionary (lower interest rate) than it would have been otherwise.

Figure 4: Monetary policy bears the cost of adjustment

Even if we assume that the monetary authority is a Stackelberg leader where the ECB autonomously decides its policy having taken into consideration the aggregate fiscal response, (point S in Figure 4), monetary policy is still more expansionary than the shock would dictate (at point A).

Had fiscal authorities been able to strike a bargain and coordinate, then fiscal policy would be more active. The ECB would have had to react by less therefore, shown by the points NC(EU) and SC for the Nash and Stackelberg game respectively, which are moved in a north-easterly direction.

Figures 1-4 show that the lack of coordination between fiscal authorities induces an aggregate outcome where the instrument is underused and monetary policy is too expansionary. So, for monetary policy to be able to do less, there must be greater fiscal cooperation between countries and an appreciation of the fact that monetary union imposes strategic interdependencies that need to be dealt with.

These are the types of failures that discussions on the fiscal framework should aim to correct with a view to promoting more cooperative outcomes.

This blog post was part of a lecture we gave at the Scottish Economic Society Annual Conference on 26 April 2021, in honour of Professor Andrew Hughes Hallett. We thank Peter McAdam for inviting us to the session.

Recommended citation:

Demertzis, M. and N. Viegi (2021) ‘Policy coordination failures in the euro area: not just an outcome, but by design’, Bruegel Blog, 20 December

Republishing and referencing

Bruegel considers itself a public good and takes no institutional standpoint. Anyone is free to republish and/or quote this post without prior consent. Please provide a full reference, clearly stating Bruegel and the relevant author as the source, and include a prominent hyperlink to the original post.