Blog Post

European banking supervision: compelling start, lingering challenges

The new European banking supervision system is broadly effective and, in line with the claim often made by its leading officials, tough and fair, but there are significant areas for future improvement.

European banking supervision (also known as the Single Supervisory Mechanism) is the first step in Europe’s banking union. Some 18 months after its official start on 4 November 2014, Bruegel has published what we believe is the first in-depth early assessment of how it works in practice (Schoenmaker & Véron, 2016). We go beyond the European perspective, and look closely at nine member states, with country-specific chapters written by recognised local experts. This two-level perspective is still necessary: banking supervision was almost entirely national until 2014, and national idiosyncrasies will continue to shape the system for a long time, both in terms of banking models and structures and in terms of perceptions and politics.

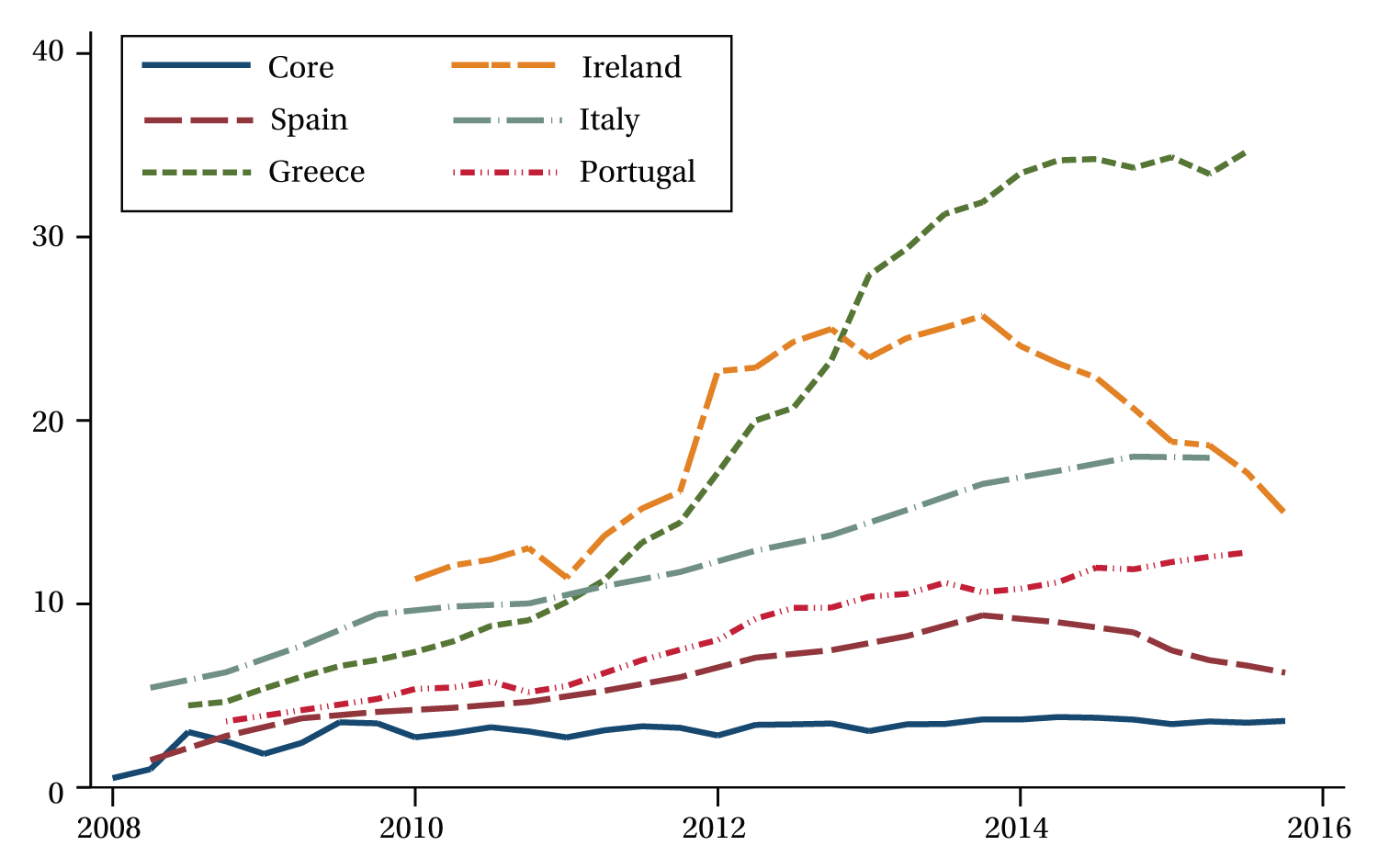

Following the great financial crisis, the euro-area banking system is still characterised by significant variations in bank strength, across banks and across countries. Figure 1 illustrates this heterogeneity by comparing non-performing loan (NPL) rates in several member states. This chart supports the view that Greece, Italy and Portugal, in particular, are still far from having brought their banking systems back to soundness, while Ireland and Spain are, after a major restructuring and recapitalisation of their banking system, more advanced on a path towards recovery.

Figure 1. Non-performing loans (% of total gross loans)

Notes: “Core” refers to a simple average of Austria, Belgium, France, and the Netherlands (Germany is omitted for lack of data availability). Source: Schoenmaker & Véron (2016), based on IMF Financial Soundness Indicators database.

Assessment

On the basis of data analysis, numerous interviews with officials and market participants, and the nine country-specific chapters, we find the new European banking supervision system to be broadly effective and, in line with the claim often made by its leading officials, tough and fair. These are remarkable achievements given the complexity of the transition from the previous regime. That said, we also identify significant areas for future improvement.

- European banking supervision is effective. Supervision of cross-border banking groups in the euro area is conducted in a joined-up manner that contrasts with the previous fragmented, country-by-country practice. The key mechanism is the operation of Joint Supervisory Teams (JSTs), which for each supervised banking group enable information sharing between the ECB and relevant national supervisors while providing a clear line of command and decision-making. The size of JSTs (up to several dozen examiners) also allows for specialisation on topics such as capital and governance. Remarkably, the new system has proved its ability to effectively manage crises from the start, with its adept handling of the banking aspects of the Greek crisis of 2015.

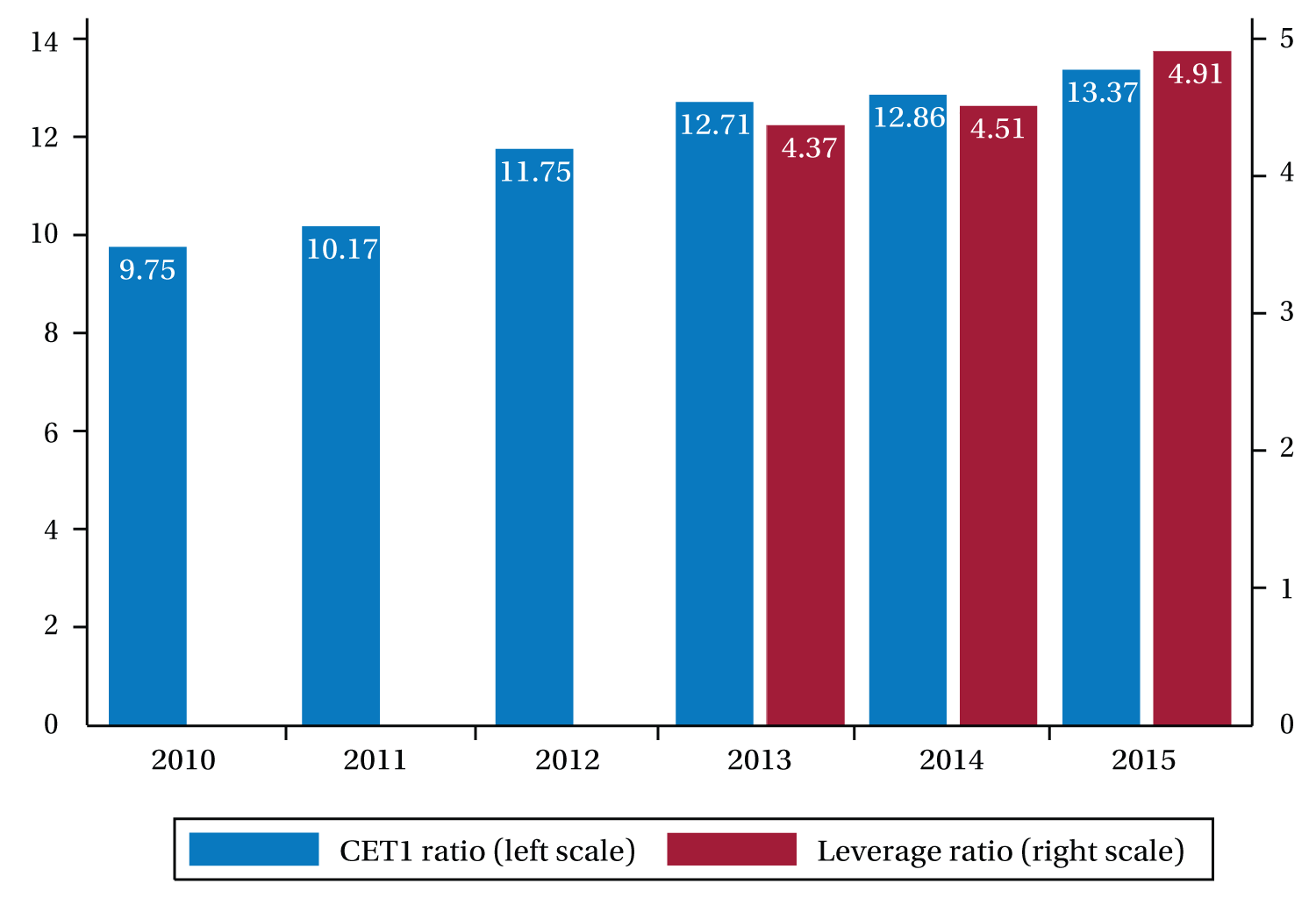

- European banking supervision is tough, at least when it comes to significant (larger) banks. It is generally more intrusive than previous national regimes, with supplementary questions during investigations and more on-site visits. This is illustrated by publicly available information in many countries, and not least by current developments in the Italian banking system. The ECB appears less vulnerable than national authorities to regulatory capture and political intervention. It has not shied away from imposing higher capital requirement add-ons under its Supervisory Review and Evaluation Process (SREP). That said, loopholes persist, not least in terms of lopsided compliance with the Basel III international framework. Furthermore, few changes have been introduced so far for the supervision of less significant banks, which still varies significantly in different countries but appears generally less demanding than that of significant banks. Figure 2 illustrates the strengthening of capital ratios for the 100 significant euro-area banking groups directly supervised by the ECB (the other 29 significant banks supervised by the ECB are subsidiaries and branches of non-euro area banks).

Figure 2. CET1 capital ratio and leverage ratio (in %)

Notes: CET1 capital ratios and leverage ratios are aggregated by computing an average of banks’ ratios weighted by total assets, for the 100 euro-area significant banking groups. Source: Schoenmaker & Véron (2016), based on SNL Financial data.

- European banking supervision appears to be broadly fair, at least for significant banks. Among these, we have not found compelling evidence of country- or institution-specific distortions or special treatment by the ECB, for example in the determination of SREP scores. The situation is more complex when it comes to less significant banks that remain subject to national supervision, including those tied together in what EU legislation calls Institutional Protection Schemes. Nevertheless, we found strong differences in domestic systemic buffers for the large banks, which are still set by the national supervisors. Most northern member states generally apply higher systemic buffers of up to 2 or 3 percent, while southern member states apply low systemic buffers of up to 1 percent. Italy and Latvia have even set the systemic buffer for their domestic systemically important banks at 0 percent.

- European banking supervision makes mistakes. There have been cases of overlapping and redundant data requests. The ECB’s communication on Maximum Distributable Amounts (MDA) was ill-prepared and contributed to volatility on bank equity markets in early 2016.[1] A perhaps more significant concern is that the Supervisory Board appears to act as a bottleneck (eg delays in the decisions on fit-and-proper tests of new managers) and does not optimise its use of delegation for day-to-day decisions.

- European banking supervision is insufficiently transparent. The ECB’s Supervisory Board and SREP process are seen as a black box by numerous stakeholders. Banks complain about the opacity of the determination of SREP scores, which are based on multiple factors. European banking supervision still provides pitifully little public information about all supervised banks, in stark contrast to US counterparts. In the report, we do our best to provide relevant details on the 129 significant banks currently supervised at the European level, but we strongly believe such information (and more) should be directly and regularly provided by the ECB itself.

- European banking supervision has not yet broken the bank-sovereign vicious circle and created a genuine single banking market in the euro area. Many lingering obstacles to a level playing field are outside European banking supervision’s remit, including deposit insurance, many macro-prudential decisions, and many other important policy instruments that remain at national level. But even within its present scope of responsibility, European banking supervision maintains practices that contribute to cross-border fragmentation, such as the imposition of entity-level (as opposed to group-level) capital and liquidity requirements, also known as geographical ring-fencing, and the omission of geographical risk diversification inside the euro area in stress test scenarios. It has not yet put an end to the high home bias towards domestic sovereign debt in many banks’ bond portfolios. Nor have many cross-border acquisitions been approved by ECB banking supervision so far.

Even so, we are impressed overall by the achievements of European banking supervision during its first 18 months. At the same time, what remains to be done to achieve the vision of European banking union is daunting. Much of this unfinished business lies beyond the remit of European banking supervisors’ authority, but materially depends on their ability to establish credibility and trust. Almost four years after the inception of banking union in late June 2012, these are still very early days in a momentous transition. On the basis of the assessment presented in the report, we find grounds for cautious optimism.

Reference

Dirk Schoenmaker and Nicolas Véron (editors), “European Banking Supervision: The First Eighteen Months” Bruegel Blueprint #25, June 2016, with country-specific chapters by Thomas Gehrig (Austria), André Sapir (Belgium), Philippe Tibi (France), Sascha Steffen (Germany), Miranda Xafa (Greece), Marcello Messori (Italy), Casper G. de Vries and Dirk Schoenmaker (Netherlands), Antonio Nogueira Leite (Portugal), and David Vegara (Spain).

[1] Supervisors have to decide how much of a bank’s earnings should be retained as capital and how much is allowed to be distributed as dividend or coupons, the latter being known as MDA. ECB banking supervision took a long time to reach the conclusion that MDA should be based on “Pillar-2” capital requirements and that these should therefore be disclosed publicly by the supervised banks, in contrast to most prior practice in the euro area.

Republishing and referencing

Bruegel considers itself a public good and takes no institutional standpoint. Anyone is free to republish and/or quote this post without prior consent. Please provide a full reference, clearly stating Bruegel and the relevant author as the source, and include a prominent hyperlink to the original post.