Blog Post

The economics of crime and punishment

What’s at stake: The Senate announced this week revisions to a sentencing reform bill – the Sentencing Reform and Corrections Act – that would lower mandatory minimums for some low-level drug crimes.

Jason Furman and Douglas Holtz-Eakin writes that Congress is considering bipartisan legislation to loosen tough sentencing laws. Inimai M. Chettiar writes that it would also give judges the discretion to depart from minimum sentences for low-level offenders if they believe specific circumstances of the crime warrant it. Most importantly, these changes would put resources where it matters: arresting, prosecuting and punishing those who commit the most serious and violent crimes. The Brennan Center writes that the legislation was revised in recent weeks to address concerns from some Republicans who said the previous version would endanger public safety.

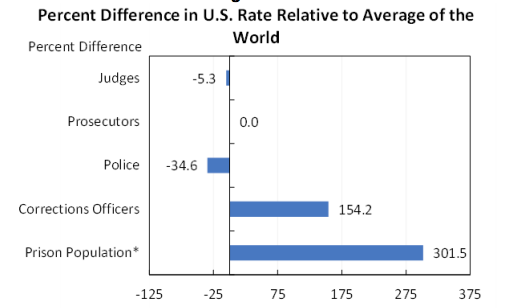

Source: White House

The economics of deterrence

Aaron Chalfin and Justin McCrary write that deterrence is important not only because it results in lower crime but also because, relative to incapacitation, it is cheap. Offenders who are deterred from committing crime in the first place do not have to be identified, captured, prosecuted, setenced, or incarcerated. For this reason, assessing the degree to which potential offenders are deterred by either carrots (better employment opportunities) or sticks (more intensive policing or harsher sanctions) is a first order policy issue.

Alex Tabarrok writes that in the economic theory, crime is in a criminal’s interest. Both conservatives and liberals accepted this premise. Conservatives argued that we needed more punishment to raise the cost so high that crime was no longer in a criminal’s interest. Liberals argued that we needed more jobs to raise the opportunity cost so high that crime was no longer in a criminal’s interest.

Aaron Chalfin and Justin McCrary writes that the earliest formal model of criminal offending in economics can be found in Becker’s seminal 1968 paper, Crime and Punishment: An Economic Approach. The crux of Becker’s model is the idea that a rational offender faces a gamble. He can either choose to commit a crime and thus receive a criminal benefit (albeit with an associated risk of apprehension and subsequent punishment) or not to commit a crime (which yields no criminal benefit but is risk free). Crime becomes more attractive when the disutility of apprehension is slight (e.g., less unpleasant prison conditions), and it becomes less attractive when the utility of work is high (e.g., a low unemployment rate or a high wage). Becker operationalizes the disutility associated with capture using a single exogenous variable, f, which he refers to as the severity of the criminal sanction upon capture. Typically, f is assumed to refer to something like a fine, the probability of conviction, or the length of a prison sentence.

Crime, rationality and shortsightedness

Alex Tabarrok writes that in a famous section of his paper, Becker argues that an optimal punishment system would combine a low probability of being punished with a high level of punishment if caught. This was Becker’s greatest mistake. We have now tried that experiment and it didn’t work. Beginning in the 1980s we dramatically increased the punishment for crime in the United States but we did so more by increasing sentence length than by increasing the probability of being punished.

Aaron Chalfin and Justin McCrary write that while there is considerable evidence that crime is responsive to police and to the existence of attractive legitimate labor market opportunities, there is far less evidence that crime responds to the severity of criminal sanctions. The evidence suggests that individuals respond to the incentives that are the most immediate and salient. While police and local labor market conditions influences costs that are borne immediately, the cost of a prison sentence, if experienced at all, is experienced sometime in the future. To the extent that offenders are myopic or have a high discount rate, deterrence effects will be less likely.

Alex Tabarrok writes that longer sentences didn’t reduce crime as much as expected because criminals aren’t good at thinking about the future; criminal types have problems forecasting and they have difficulty regulating their emotions and controlling their impulses. In the heat of the moment, the threat of future punishment vanishes from the calculus of decision. Thus, rather than deterring (much) crime, longer sentences simply filled the prisons. As if that weren’t bad enough, by exposing more people to criminal peers and by making it increasingly difficult for felons to reintegrate into civil society, longer sentences increased recidivism.

Alex Tabarrok writes that instead of thinking about criminals as rational actors, we should think about criminals as children. In the criminal as poorly-socialized-child theory, crime is often not in a person’s interest but instead is a spur of the moment mistake. One thing all recommendations have in common is that for kids the consequences for inappropriate behavior should be quick, clear, and consistent. Quick is one way of lowering cognitive demands and making consequences clear. Consequences can also be made clear with explanation and reasoning. Finally, consistent punishment, like quick punishment, improves learning and understanding by reducing cognitive load.

Peter R. Orszag writes that raising the probability of arrest seems far more likely to deter crime than longer prison sentences do. After all, most people, let alone most criminals, seem more motivated by near-term consequences (the chance of arrest) than long-term ones. Alex Tabarrok writes that we need to change what it means to be “tough on crime.” Instead of longer sentences let’s make “tough on crime” mean increasing the probability of capture for those who commit crimes.

Republishing and referencing

Bruegel considers itself a public good and takes no institutional standpoint. Anyone is free to republish and/or quote this post without prior consent. Please provide a full reference, clearly stating Bruegel and the relevant author as the source, and include a prominent hyperlink to the original post.