Blog Post

The abandonment of counter-cyclical fiscal policy

What’s at stake: The reluctance to use fiscal policy as a stabilizing tool in the current deflationary environment has been puzzling to many and a number of authors are now putting forward possible explanations.

The move from counter-cyclicality to procyclicality

In its 2015 Fiscal Monitor, the IMF writes that to be stabilizing, the fiscal balance needs to increase when output rises and to decrease when it falls. That way, fiscal policy generates additional demand when output is weak and subtracts from demand when the economy is booming.

Jeffrey Frankel writes that the heyday of activist fiscal policy was 50 years ago. The position “we are all Keynesians now” was attributed to Milton Friedman in 1965 and to Richard Nixon in 1971. In the late 20th century, most advanced countries managed to pursue countercyclical fiscal policy on average: generally reining in spending or raising taxes during periods of economic expansion and enacting fiscal stimulus during recessions. The result was generally to smooth out the business cycle (as Keynes had intended). It was the developing countries who tended to follow procyclical or destabilizing policies. After 2000 many political leaders in advanced countries pursued procyclical budgetary policies: they sought fiscal stimulus at times when the economy was already booming, thereby exaggerating the upswing, followed by fiscal austerity when the economy turns down, thereby exacerbating the recession.

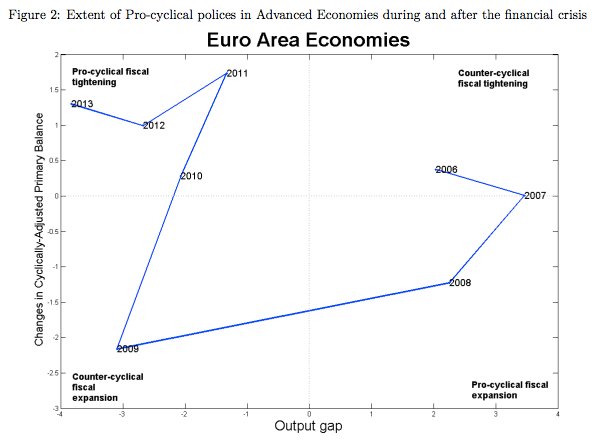

Alesina and al. (2014) show in the Figure reproduced below how the fiscal policy of Euro Area economies changed overtime, in relation to the economic cycle. For every year we show the change in the cyclically adjusted primary balance and the level of the output gap. The first and third quadrants represent episodes of counter-cyclical fiscal policy where governments squeeze the public budget while the economy is overheating, and vice versa. On the contrary, the second and fourth quadrants include years in which fiscal policy was pro-cyclical. The majority of the countries in the sample adopted counter-cyclical fiscal policies at the beginning of the recession (2008-09) but turned pro-cyclical after 2009, namely fiscal consolidations started when recessions were not over yet.

Source: Alesina and al. (2014)

A general theory of austerity

Simon Wren-Lewis writes that there was no good macroeconomic reason for austerity at the global level over the last five years, and austerity seen in periphery Eurozone countries could most probably have been significantly milder. As austerity could have been so easily avoided by delaying global fiscal consolidation by only a few years, a critical question becomes why this knowledge was not applied.

Simon Wren-Lewis writes that one set of arguments point to an unfortunate conjunction of events: austerity as an accident if you like. Basically Greece happened at a time when German orthodoxy was dominant. This explanation cannot play more than a minor role: mainly because it does not explain what happened in the US and UK, but also because it requires us to believe that macroeconomics in Germany is very special and that it had the power to completely dominate policy makers not only in Germany but the rest of the Eurozone.

Simon Wren-Lewis writes that austerity was instead the result of right-wing opportunism, exploiting instinctive popular concern about rising government debt in order to reduce the size of the state. This opportunism, and the fact that it was successful, reflects a failure to follow both economic theory and evidence. This failure was made possible in part because the task of macroeconomic stabilization has increasingly been delegated to independent central banks, but these institutions did not actively warn of the costs of premature fiscal consolidation, and in some cases encouraged it.

Larry Summers write that despite the overwhelming case for infrastructure investment, there is great resistance from those who think it will be carried out ineptly. It is understandable to doubt about the government’s ability to do big things when it fails in executing some of its routine responsibilities. In an era when public trust in government remains near all-time lows, every public task is freighted with consequence. The relationship is cyclical — if government can start being more effective, it will win more trust, leading to more effectiveness.

Josh Bivens notes that in the US the federal budget season came and went this year without any budget proposal hitting the floor of the U.S. House of Representatives. For Germany, Brad Setser writes that nothing appears to trump the commitment to balanced budgets right now. The long tradition of viewing public investment as different from public consumption and more amenable to debt financing has been forgotten as Germany’s governing coalition has made the black zero (the schwarze Null) the central goal of economic policy.

Emerging economies graduating from procyclicality

Otaviano Canuto, Francisco Carneiro, and Leonardo Garrido write that evidence on the procyclical pattern of fiscal policy in developing countries was first found by Gavin and Perotti (1997), who showed that Latin American was much more expansionary in good times and contractionary in bad times. Talvi and Vegh (2000) then showed that such behaviour was far from being a trademark of Latin America alone as many other developing countries across the world espoused a procyclical fiscal policy stance. There are a number of different explanations as to why developing countries tend to behave in this way vis à vis industrialised economies. Some of the reasons most commonly found in the literature include credit constraints and political economy considerations.

Jeffrey Frankel writes that some developing countries did achieve countercyclical fiscal policy after 2000. They took advantage of the boom years to run budget surpluses, pay down debt and build up reserves, which allowed them the fiscal space to ease up when the 2008-09 crisis hit. Chile is the poster boy of those who “graduated” from procyclicality. Others include Botswana, Malaysia, Indonesia, and Korea. Unfortunately some, like Thailand, who achieved countercyclicality in the last decade have suffered backsliding since then. Brazil, for example, failed to take advantage of the renewed commodity boom of 2010-11 to eliminate its budget deficit, which explains much of the mess it is in today now that commodity prices have fallen.

Republishing and referencing

Bruegel considers itself a public good and takes no institutional standpoint. Anyone is free to republish and/or quote this post without prior consent. Please provide a full reference, clearly stating Bruegel and the relevant author as the source, and include a prominent hyperlink to the original post.