Blog Post

The implications of the Panama Papers

What’s at stake: The Panama Papers leaked last week raised important questions about the role of tax havens. We explain the mechanics of tax evasion and review the most important lessons to take away from the leaks.

Some numbers regarding off-shore tax havens

- Mossack Fonseca, the law firm whose documents were leaked, worked with more than 14,000 banks, law firms, company incorporators and other middlemen to set up companies, foundations and trusts for customers.

- Gabriel Zucman estimated in his paper ‘The Missing Wealth of Nations’ (2013) that 8% of the global financial wealth of households is held in tax havens, three-quarters of which goes unreported in official statistics.

- In an interview, Zucman states that 8% is a global average which conceals significant heterogeneity: the U.S. has around 4% of its financial wealth offshore, Europe around 10%, but in Latin America this number is closer to 20%, in Africa to 30%, and in Russia the percentage is around 50%.

- Zucman’s paper states that about 40% of the world’s foreign direct investments are routed through tax havens. In 2008, foreigners held foreign securities worth $2 trillion through Switzerland bank deposits and portfolios: this is equal to China’s foreign exchange reserves. In 2008, only one-third of all foreign securities in Swiss banks belonged to Swiss savers – two-thirds belonged to foreigners.

- According to the the U.S. Council of Economic Advisers, via the NYT, American-controlled corporations domiciled in places like the Cayman Islands or the British Virgin Islands often earn profits that are greater than the gross domestic products of these island nations: 1578% of GDP in Bermuda, 1430% in Cayman Islands, 1009% in British Virgin Islands.

- Gabriel Zucman compares the statutory tax rate with what actually gets paid in the U.S. The nominal corporate tax rate has been 35% since 1993, but the proportion of U.S. corporate profits actually collected by the Internal Revenue Service (the effective tax rate) has never reached even 30% in the years since that change and in 2013 stood at around 16%. Zucman estimates that offshore tax schemes are responsible for about two-thirds of the decline in the effective tax rate since 1998, representing a loss of over $100 billion for the U.S. treasury in 2013.

- Tax avoidance costs EU countries €50-70 billion a year in lost tax revenues according to the European Commission.

The mechanics behind tax havens

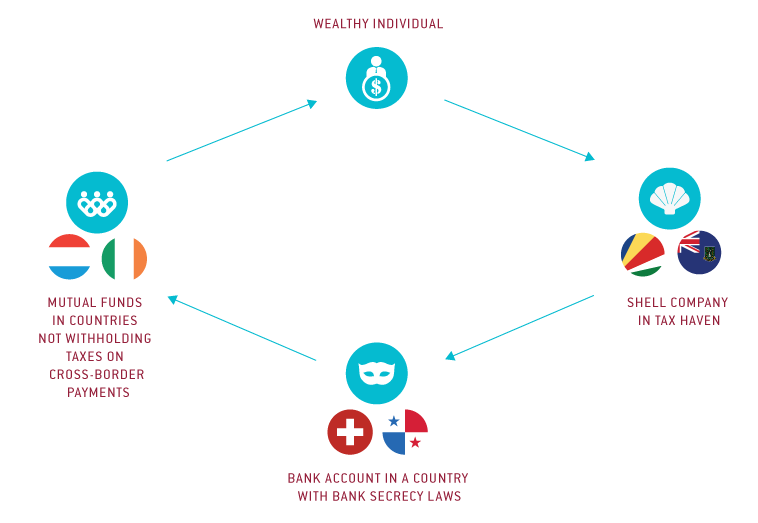

In his 2013 paper, Zucman also explains the mechanics of tax avoidance through offshore banking and shell companies. The function of offshore financial centres is to help foreigners invest outside of these centres, the banks acting only as conduits: using Swiss data, he shows that on their Swiss accounts, foreigners do own some U.S. equities, but they mostly own Luxembourg and Irish fund shares (the funds, in turn, invest all around the world).

Investing in a Luxembourg fund through a Swiss account makes perfect sense for a French tax evader: Luxembourg does not tax cross-border payments, so the tax evader receives the full dividend paid by the fund on his or her account, and French personal income tax can be evaded, since there is no automatic exchange of information between Swiss banks and the French tax authority.

Swiss banks provide a unique kind of deposit owned by households only, in the form of what are known as fiduciary deposits. Fiduciary deposits cannot be used as a medium of exchange: they are useless for corporations. Swiss banks invest the funds placed in fiduciary deposits in foreign money markets on behalf of their clients. Legally speaking, all interest is considered to be paid by foreigners to the depositors, with the Swiss banks acting merely as “fiduciaries.” Thus, fiduciary deposits are not subject to the 35% Swiss advance tax.

He shows that most Swiss fiduciary deposits held by foreigners are actually held in the name of sham corporations set up in tax havens such as Panama, Liechtenstein and the British Virgin Islands. He concludes that once you understand the purposes that sham corporations serve, it becomes clear that most fiduciary deposits assigned to tax havens by the Swiss National Bank belong to residents of rich countries, in particular to Europeans.

Source: Bruegel

Corporate tax repatriation

Gillian Tett states that there are not many questions on which a man such as Tim Cook, chief executive officer of Apple, would agree with Donald Trump. Corporate tax is one (a Bloomberg article reports that the overseas cash piles of American companies amount to $2.1 trillion). Trump’s tax plan would enable the repatriation at a lower rate of tax of profits earned around the world and held overseas, as long this cash is “put to work in America”.

Leaving aside populist arguments, she argues that the once-geeky debate over repatriation could end up part of the mainstream debate in the next year. In an ideal world, corporation tax should be lowered to a more competitive level while removing loopholes: this would remove the rationale for overseas hoarding. But in the real world introducing a repatriation deal, even at 10%, would be better than a world of ever-growing offshore cash piles, transatlantic tax battles and lousy infrastructure.

In 2003, the European Union adopted the Savings Directive in a move to curb tax evasion: since then, Swiss and other offshore banks have had to withhold a tax on interest earned by European Union residents. In his paper, Zucman points out that the directive only applies to accounts opened by European households in their own name; sham corporations are a straightforward way of eschewing it. He shows that there is a clear negative correlation between the share of fiduciary deposits held by Europeans and the share of fiduciary deposits assigned to tax havens. European depositors reacted particularly strongly to the introduction of the EU Savings Directive: between December 2004 and December 2005, when the directive became applicable, Europe’s share of Swiss fiduciary deposits declined by 10 percentage points, while tax havens gained 8 percentage points.

Lessons to be learned

Daniel Hough states that the panama papers are a chance to fix a long broken system. UK Prime Minister David Cameron will host an international anti-corruption summit in London in May. Hough notes that this could end up as nothing more than a talking shop. But it might also be the perfect forum to push for an international agreement on stricter rules concerning beneficial owners. It is also a moment to get commitments to actually implement such legislation. The Panama Papers should serve as a wake up call to finally change the long outdated rules and regulations that shape international financial transactions.![]()

Gabriel Zucman adds that the main way to fight the abusive use of shell companies would be to find who owns this wealth, by creating comprehensive registries which record the beneficial owners of U.S. real estate and financial securities. This would be a powerful way to promote financial transparency, fight money laundering, the financing of terrorism and tax evasion. There are already registries for real estate and land: these should also be expanded to cover financial assets – equities, bonds, mutual fund shares and derivatives. The Economist is also in favour of central registers on beneficial ownership that are open to tax officials, law-enforcers, and the public. Law firms and other intermediaries that set-up and husband offshore companies and trusts should also be regulated. They are supposed to know their clients, weeding out the dodgy ones. Governments should start by making it a criminal offence to enable tax evasion by others.

On 12 April, the European Commission proposed public tax transparency rules for multinationals, which build on other proposals to introduce sharing of information between tax authorities.The new rules would require multinationals operating in the EU with global revenues exceeding EUR 750 million a year to publish key information on where they make their profits and where they pay their tax in the EU on a country-by-country basis. The same rules would apply to non-European multinationals doing business in Europe. In addition, companies would have to publish an aggregate figure for total taxes paid outside the EU.

Germany and France have also released separate plans to accelerate the fight against tax evasion and tax fraud. The Financial Times reports that Finance ministers Wolfgang Schäuble and Michel Sapin, who led the way on previous global financial transparency projects, such as the automatic exchange of information between banks, want to seize the opportunity created by the Panama Papers leak to force through further reforms.

Tim Harford says that there is something disheartening about the name-and-shame, patch-and-mend turn the conversation has taken. Many people who dodge tax have never used an offshore financial centre. Tax systems in many developed economies are riddled with holes — the euphemism is “deductions” — created to win support from domestic interest groups. Other loopholes exist because national authorities cannot get their act together to standardise their systems. Neither leaks from Panama nor the ad hoc manoeuvres of the US Treasury fix this. Harford argues that this week’s tantrums over taxation have served a useful purpose. Now we need to take a deep breath and do the hard work of broadening, simplifying and harmonising our systems. But here is the problem: if politicians succeed, everyone will find something to dislike about the results.

Richard Ray argues that many of those who benefit from offshore centres — including millions receiving workplace pensions — are not aware of the key role they play in their financial affairs. Such financial centres facilitate trade, investment, economic growth, create jobs and increase the rate of return for savings. On transparency, he cites peer reviews conducted by the Financial Action Task Force and the OECD, which show that British offshore centres have robust transparency standards. According to Ray, the true appeal of the UK offshore centres lies in their widely trusted British-inspired laws, courts, and professionals. The predictability and security offered by British institutions make such jurisdictions magnets for investors seeking reliable structures for international investment. A 2013 study conducted by Capital Economics found that Jersey supports more than 140,000 British jobs and generates £2.5bn a year in tax for the exchequer, as much as the UK loses through all tax avoidance, onshore and offshore, combined.

Conversely, Zucman argued in a 2014 paper that not only do offshore machinations reduce government revenues that could offset other taxes and fund public services, but they also induce a wasteful response by corporations that has its own non-negligible cost. There are thousands, perhaps even millions of people around the world, who spend their working lives devising tax-reduction schemes, fielding phone calls or handling paperwork to establish offshore accounts, or preparing the complicated tax returns required to sustain these schemes. Even for those who believe corporate taxes are too high, allowing offshore tax havens to effectively reduce corporate tax bills is far less efficient than actually reducing the statutory rate.

The panama papers and the art market

As pointed out by the New York Times, the Panama papers also reveal just how critical a role secrecy plays in the art market today. Nouriel Roubini argued in 2015 that regulation is needed in the art market, because of its vulnerability to routine trading on inside information, price manipulation through guarantees offered by dealers on auctioned work, and tax avoidance by the transfer of paintings within families. He pointed out that one reason why the art market was so strong in the US was favourable tax treatment. Inside information is also considered standard, whereas in other markets it is thought of as being illegal. He added that the art market was prone to “fads, passions, manias, booms and busts,” because art works have no clear financial value and the market is opaque.

Republishing and referencing

Bruegel considers itself a public good and takes no institutional standpoint. Anyone is free to republish and/or quote this post without prior consent. Please provide a full reference, clearly stating Bruegel and the relevant author as the source, and include a prominent hyperlink to the original post.