Blog Post

Lost in assumptions: assessing the economic impact of migrants

What’s at stake: Many research institutes have estimated the economic impact of migrants, in particular regarding fiscal budgets and the labour market. These studies often give contradictory results. This blogs review looks at the different assumptions and approaches behind these results.

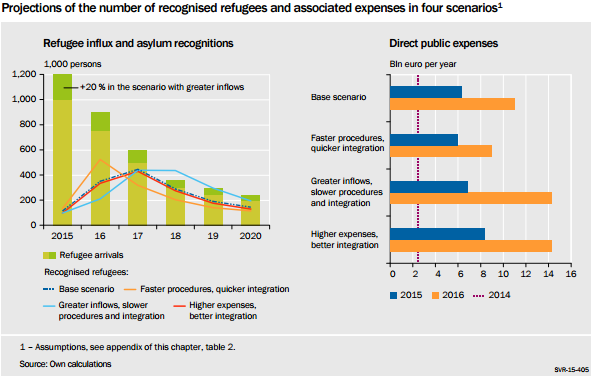

The German Council of Economic experts describes four scenarios for labour force potential and expenditures related to refugees. They divide integration into 3 stages: asylum application, approval and labour market integration. The scenarios are linked to assumptions on direct fiscal expenses during the 3 stages of integration.

Base scenario

This assumes that the asylum application takes 4 months, and the decision8 months. Asylum applicants receive benefits, then benefits continue if they are recognized as refugees, or they receive a lump sum after rejection. The report assumes a 40% participation rate and an 80% unemployment rate upon recognition. After 5 years, they assume that the participation rate increases to 70%, while the unemployment rate drops to 20%.

Faster procedures, quicker integration

The second scenario assumes 6 months from arrival to asylum decision, and faster labour market integration, with an 80% participation rate after 5 years and a 10% unemployment rate.

Greater inflows, slower procedures, slower integration

The third view assumes 20% more arrivals per year than in the base scenario, 18 months until the asylum decision and slower labour market integration, with a participation rate of 60% and an unemployment rate of 30% after 5 years.

Higher expenses better integration

The last scenario assumes higher benefits for asylum applicants, and higher lump sums for both training measures and upon rejection. Labour market integration is assumed to be better than in the second scenario, with an unemployment rate of 5% after 5 years, while the participation rate is also assumed to be 80% after 5 years.

Importantly, all the scenarios assume that the number of refugees coming to Germany drops relatively quickly, from a million in 2015 to 200,000 in 2020.However limiting this number would require political measures.

Depending on the scenario, migration, as well as social and integration benefits for asylum seekers and recognised refugees will result in direct annual additional gross expenses for public budgets in the range of €5.9 to €8.3 billion in 2015 and €9.0 to €14.3 billion in 2016 (0.2-0.3 % of GDP in 2015 and 0.3-0.5 % of GDP in 2016). Slower procedures combined with worse labour market integration would likely raise these costs noticeably (figure below).

Source: Annual Economic Report 2015/16 ‘Focus on Future Viability’, Sachverständigenrat

Holger Bonin investigates the impact of current immigration on the German budget. He presents a simple tax-transfer-calculation for 2012 based on data from the socio-economic panel of Germany. He finds that in 2012 , the average non-citizen paid 3300€ more in taxes than they received in terms of social transfers and free schooling.

Bertolla et al from CESifo point out that when all public expenditure is included, this number turns actually negative. They adjust Bonin’s calculations, and find a net cost of 1800€ to 1450€ per non-citizen in 2012. The key difference driving this result is the inclusion of fixed costs, such as military expenditure, in government spending.

In a second question, Bonin explores the impact of future immigration on the German budget. Here, he takes into account all public expenditures, and assumes that immigrants will have the same tax and transfer profiles as non-citizens already living in Germany, which translates into lower employment rates and lower income compared to the native population.

The author assumes similar favourable age structure of future immigration, and a yearly influx of 100,000, 200,000 and 300,000 people. Using a generational accounting study, he finds that future immigration is more of a burden to the public finances than a benefit.

He finds that for 200,000 immigrants per year, to achieve a balanced budget in an intertemporal calculation, the primary surplus would have to increase by 3.7 %, compared to 3.3 % without migration. Holger assumes that new immigrants make lower net contributions than migrants already living in Germany. Assuming migrants are higher qualified, the net burden decreases.

Christian Dustmann and Tommaso Frattini look at the fiscal impact of immigration on the UK economy since 1995. Similar to Bonin, the authors use a tax-transfer calculation based mainly on the UK Labour Force Survey to find the net fiscal contribution of migrants between 1995 and 2011.

Government expenditures on goods and services are mainly allocated pro rata to the different population groups. However, for public goods a distinction is made between pure public goods and congestible public goods, for which the costs may increase with the size of the resident population. Only the costs for the latter are assigned to migrants.

The authors find that from 1995-2011 the resident immigrant population from European Economic Area (EEA) countries made a positive fiscal contribution, while those from non-EEA countries contributed less than they received; however, native workers also make a negative contribution during this period. Moreover, they find that both groups of immigrants that arrived after 2000 made a positive contribution.

These estimates have been criticised by Migration Watch UK, mainly on the grounds that government revenue from recent migrants has been seriously overestimated, while costs of public service provision have been underestimated. Using different assumptions over the same period, Migration Watch finds negative fiscal impacts for all groups.

Rowthorn, re-evaluates Dustmann and Frattini’s estimates for recent migrants. His adjustments include all Migration Watch assumptions excluding those for debt interest and personal taxes (income tax and national insurance). They also include an adjustment for native labour displacement and his own estimate of the migrant share of debt interest. He finds negative impacts for both groups of migrants.

The 2014 update of Dustmann and Frattini does not really change their initial results (see figure below), the main difference being that more recent public expenditure data published by HM Treasury is used to allocate expenditures. As a side remark, the authors point out that migration can be temporary, and that remigration is an underexplored issue. If migrants return to their country of origin after reaching their career peak or upon retirement it would relieve to the fiscal system.

This is further explored in a socio-economic panel study at DIW by Dustmann and Görlach, who propose a general theoretical framework for modelling temporary migration decisions. The authors find that temporariness of migration has typically not been accounted for in the past. This can change results significantly, as most of the fiscal burden may be borne by the country in which migrants settle after retirement.

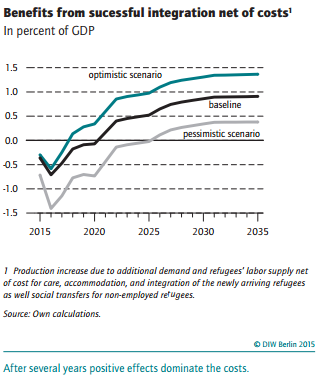

As a general critique to the studies above, Marcel Fratzscher and Simon Junker from DIW point out that measuring the economic value only in terms of taxes and government benefits received, without incorporating refugees’ contribution to economic performance, is false and misleading.

There are two sources of positive economic effects: employed refugees stimulate the economy on the supply side by contributing to corporate production and refugee-related expenditures come with positive demand impulses as high demand helps business overall.

The authors outline a model on the economic potential of refugees, capturing the effects arising in the macroeconomic cycle incorporating multipliers. They assume that the refugee influx declines gradually from 1.5 million people in 2015-2016 to half a million in 2018-2020.

They assume late entry into the labour market, with refugees taking up employment only after 2 years. The following assumptions hold:

- Baseline scenario: Unemployment rates are assumed to be 60% in years 2-5, 45% in years 6-10 and 30% in year 11 and later. Participation rate is 80%, while labour productivity is assumed to be 67%. The acceptance rate is 45%. Costs related to care, accommodation and integration during the application stage are assumed to be 40% of per capita income, while social benefits for unemployed refugees are 30% of per capita income.

- Pessimistic scenario: Unemployment rates are 65% in years 2-5, 50% in years 6-10 and 35% in year 11 or later. Participation rate is 75%, while labour productivity is assumed to be 50%, rising to 67% over time. The acceptance rate is 40%. Costs during the application stage are 66% of per capita income, while social benefits for unemployed refugees are 40% of per capita income.

- Optimistic scenario: Unemployment rates are 50% in years 2-5 falling to 38% and 25% over time. Participation rate is 85%, while labour productivity is the same of the baseline scenario. The acceptance rate is 50%, and the costs related to the first years and beyond are assumed to be half of the pessimistic scenario.

The multipliers assumed are 0.5 in the baseline and the optimistic scenario, and 0.4 in the pessimistic scenario, in order to factor mainly the direct effects. As a result, the initial costs are predominated by positive effects in the long run (see figure below). Even in an unfavourable scenario, in which significantly lower productivity and high costs are assumed, the breakeven point appears a few years later.

Source: ‘Integrating refugees: A long-term, worthwhile investment’

Republishing and referencing

Bruegel considers itself a public good and takes no institutional standpoint. Anyone is free to republish and/or quote this post without prior consent. Please provide a full reference, clearly stating Bruegel and the relevant author as the source, and include a prominent hyperlink to the original post.