Blog Post

The remarkable case of Spanish immigration

During the first decade of the twenty-first century, Spain experienced one of the largest waves of migration in European history, relative to its population. Shortly after signing the Treaty of Adherence to join the European Community in 1985, Spain went from being a sender to a receiver country.

The case of Spanish immigration is unique, due to both its magnitude and timing. During the first decade of the twenty-first century, Spain experienced one of the largest waves of migration in European history, relative to its population. Until the mid-nineties, Spain had been a country of emigrant population. From 1850-1950, approximately 3.5 million Spaniards went to Latin American countries. Further waves of emigrants left Spain during the sixties and the seventies for other European countries. However, shortly after signing the Treaty of Adherence to join the European Community in 1985, Spain went from being a sender to a receiver country.

The following sections intend to describe this phenomenon by analysing how many migrants came, what their socioeconomic characteristics were, and how migrants integrated into the labour market.

1. How many migrants?

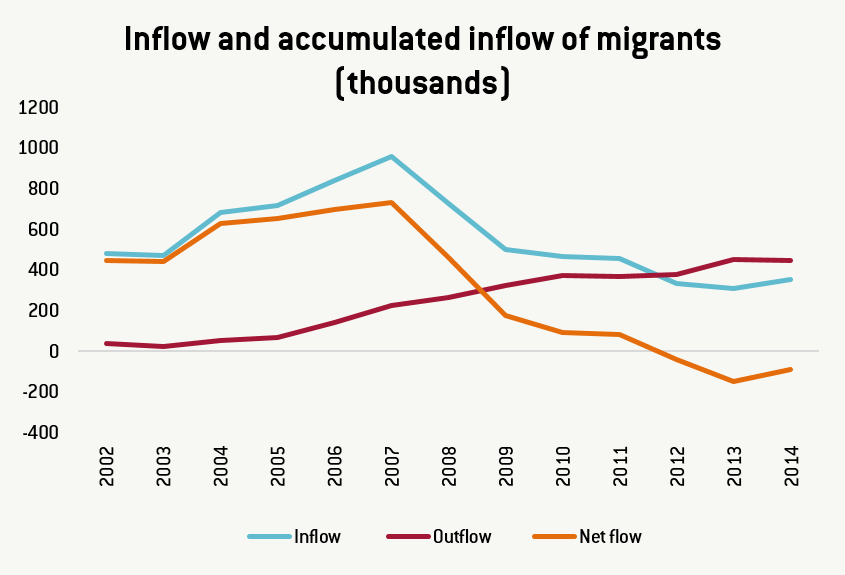

Between 2002 and 2014, Spain received an accumulated immigration inflow of 7.3 million and a net flow of 4.1 million, making it the second-largest recipient of immigrants in absolute terms among OECD countries, following the United States. Figure 1 below shows yearly inflows, outflows and net flows of foreign population throughout this period. Immigrants are defined as those born in a foreign country, and living (or intending to live) for a year or more in Spain.

This migration episode was largely concentrated during the first decade of the century, peaking in 2007. After the financial crisis the number of foreigners leaving Spain rapidly increased, while inflows became weaker, leading to much lower net flows (becoming modestly negative between 2012 and 2014).

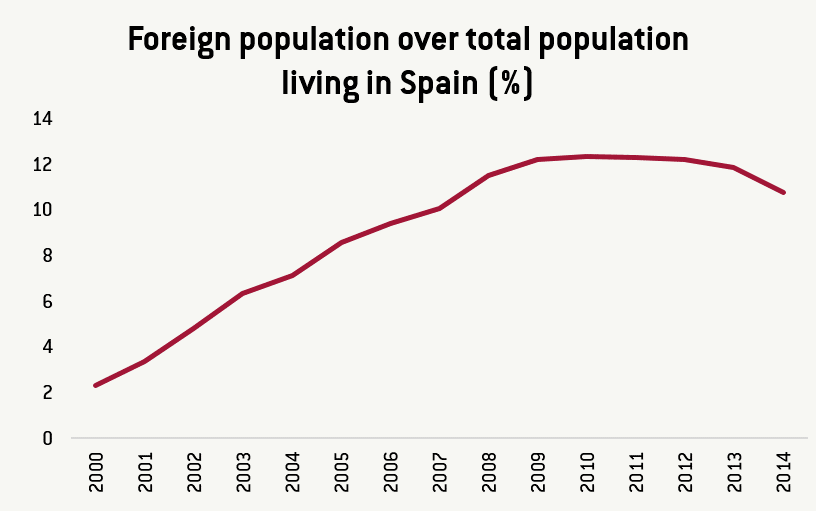

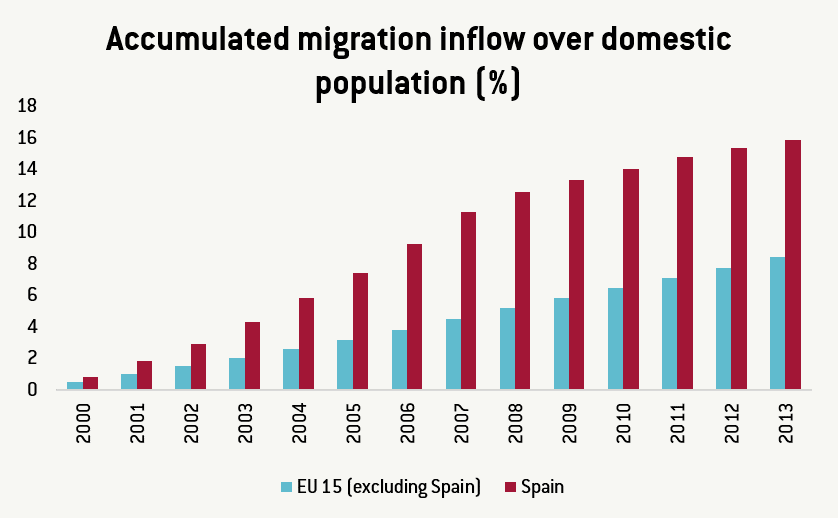

For a better understanding of these absolute numbers from the country recipient perspective, Spain went from having a total foreign population of 2% in 2000 to approximately 12% in 2011, as figure 2 shows. Figure 3 provides the magnitude of this phenomenon from a EU15 perspective. According to Eurostat data, 1 out of 5 migrants that moved to the EU15 during 2002 and 2013 went to Spain.

Figure 1

Source: Own computations based on the Residential Variation Statistics. Spanish National Institute of Statistics

Figure 2

Source: Own computations based on the Residential Variation Statistics. Spanish National Institute of Statistics

Figure 3

Source: Own computations based on the Spanish National Institute of Statistics and Eurostat

2. What were their socioeconomic characteristics?

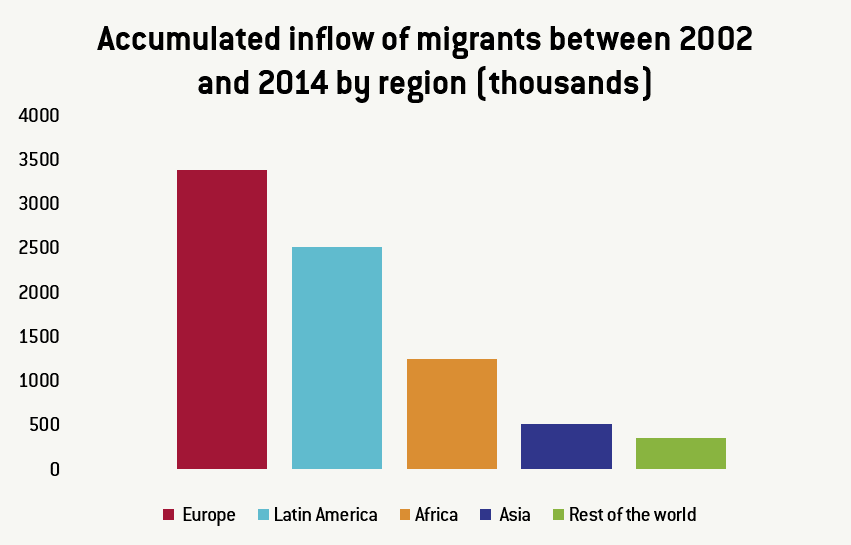

What was the origin of immigrants that moved to Spain? As figure 4 reveals, between 2002 and 2014 the vast majority of migrants came from Europe (3.4 million), Latin America (2.5 million) and Africa (1.3 million, many from Morocco).

Figure 4

Source: Own computations using data from the Spanish National Institute of Statistics

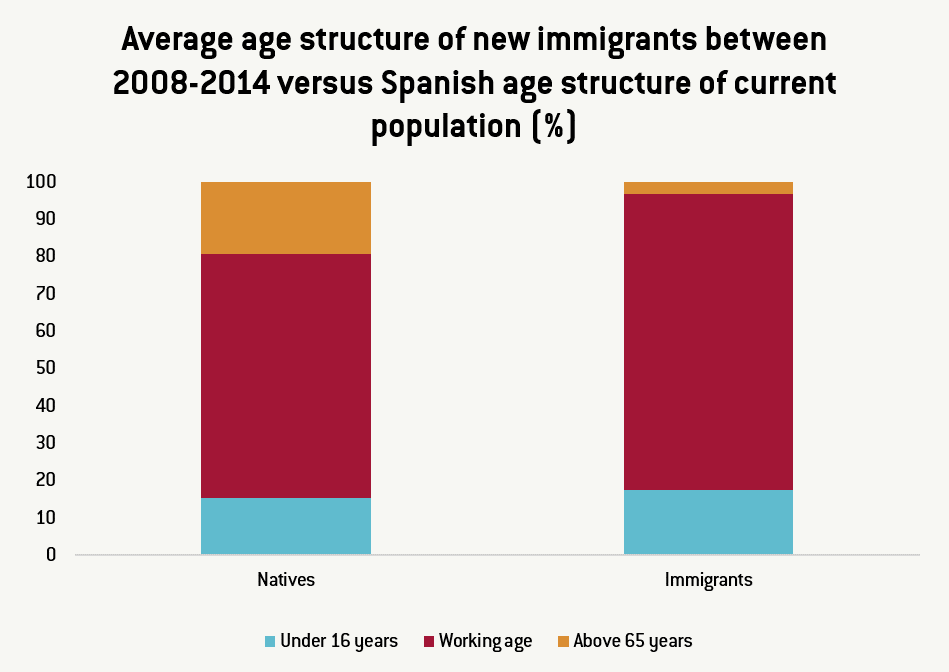

In terms of demographics, it is worth mentioning that new immigrants arriving in Spain were younger compared to the native population, as figure 5 reveals for the 2008-2014 period. On average, foreign births (where the child is born to a mother without Spanish nationality) have made up 20% of total births in Spain since 2008, while immigrants made up about 11% of the total Spanish population during this period, according to the Spanish National Institute of Statistics. This difference can be explained both by their lower median age and higher fertility rates, which partially offset the ageing tendency of the Spanish population.

Figure 5

Source: Own computations based on the Spanish National Institute of Statistics and Eurostat

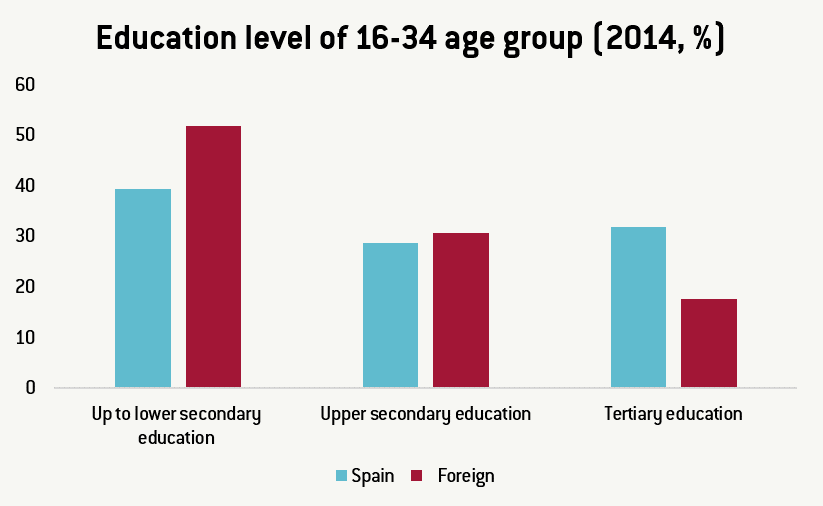

Finally, was this massive wave of migrants more or less educated compared to the nativepopulation? According to Eurostat data, the overall education attainment of the immigrant population seems to be lower for the 16-34 age group compared to the domestic population in 2014 (figure 6). However, the report “Immigration and the Welfare State in Spain” by “Obra Social La Caixa” argues that educational level largely depends on the origin of the migrant; while migrants from Latin American and African countries have lower educational attainment, the contrary is true for Europeans.

Figure 6

Source: Own computations through Eurostat data

3. The integration of migrants in the labour market

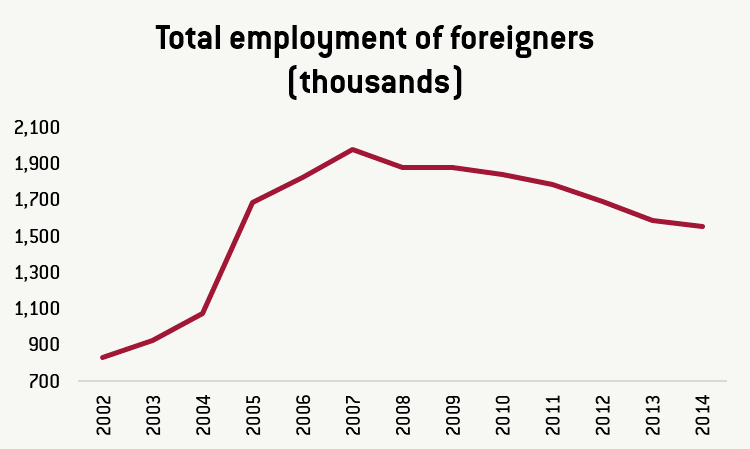

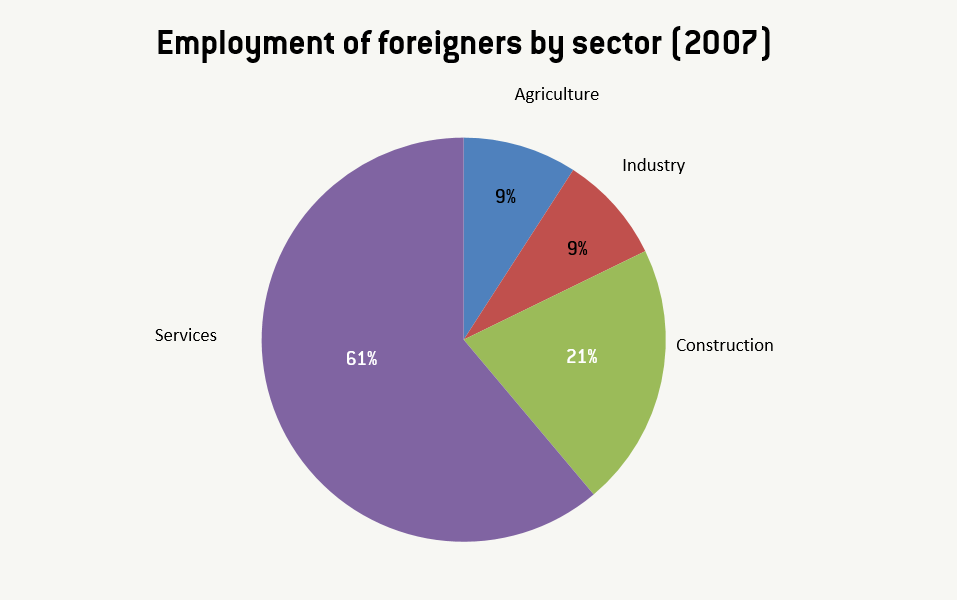

Given the large number of immigrants arriving in Spain during this period, it is natural to ask how migrants integrated into the labour market. Employment of immigrants increased significantly between 2002 and 2014, peaking in 2007 (see figure 7). However, the foreign assimilation process was not homogenous across sectors but largely concentrated in labour intensive ones, such as services and construction, as shown by figure 8.

Figure 7

Source: Own computations based on Spanish Public Service of State Employment

Figure 8

Source: Own computations based on Spanish Public Service of State Employment

Although some voices claim that immigration to Spain may have had redistribution effects across Spaniards and immigrants in terms of employment and wages, there is empirical evidence suggesting that this was not the case (Carrasco et al, 2005) prior to the financial crisis. The study estimates an elasticity of employment rate with respect to the proportion of immigrants of -0.02. This result suggests that an increase of 10% in the proportion of immigrants (as it is the case for Spain between 1998 and 2009) would lead to a decrease in employment of native workers of around 0.2%.

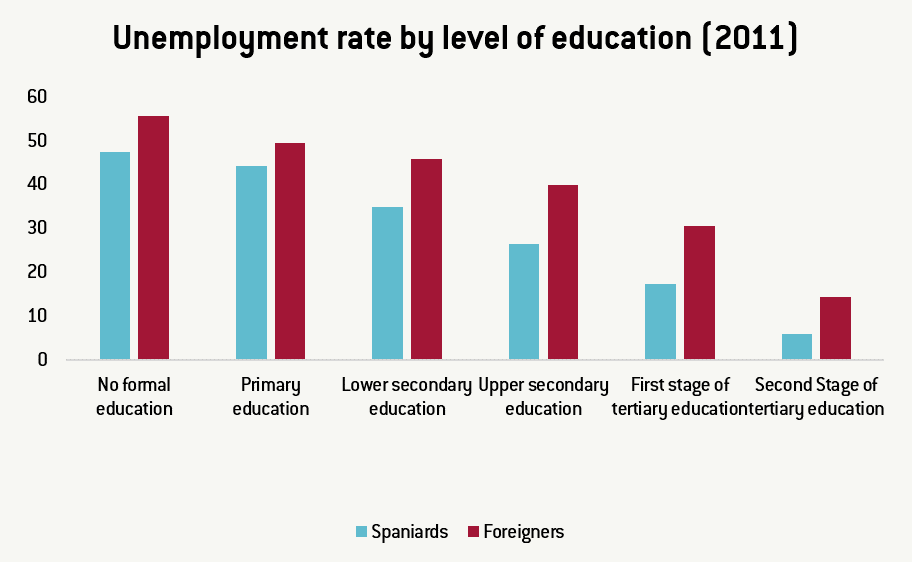

The resulting story seems quite straightforward. Before the crisis, the Spanish economy was in need of young, “low-skilled” workers willing to accept relatively low salaries. Immigration raised employment figures and promoted economic growth. Although the integration of migrants into the labour force was very successful before 2008, the financial crisis led to a disproportionate increase in unemployment rates among migrants, even holding constant educational attainment, according to Eurostat data (see below figure 9).

Although the Spanish migration phenomenon has been analysed in the economic literature, more updated research on the post-crisis effects of this episode could be of interest in order to shape the current migration agenda.

Figure 9

Source: Eurostat (2011)

Republishing and referencing

Bruegel considers itself a public good and takes no institutional standpoint. Anyone is free to republish and/or quote this post without prior consent. Please provide a full reference, clearly stating Bruegel and the relevant author as the source, and include a prominent hyperlink to the original post.