Blog Post

The computerisation of European jobs

Who will win and who will lose from the impact of new technology onto old areas of employment? This is a centuries-old question but new literature, which we apply here to the European case, provides some interesting implications.

The key takeaway is this: even though the European policy impetus remains to bolster residually weak employment statistics, there is an important second order concern to consider: technology is likely to dramatically reshape labour markets in the long run and to cause reallocations in the types of skills that the workers of tomorrow will need. To mitigate the risks of this reallocation it is important for our educational system to adapt.

Debates on the macroeconomic implications of new technology divide loosely between the minimalists (who believe little will change) and the maximalists (who believe that everything will).

In the former camp, recent work by Robert Gordon has outlined the hypothesis that we are entering a new era of low economic growth where new technological developments will have less impact than past ones. Against him are the maximalists, like Andrew McAfee and Erik Brynjolfsson, who predict dramatic economic shifts to result from the coming of the ‘Second Machine Age’. They expect a spiralling race between technology and education in the battle for employment which will dramatically reshape the kind of skills required by workers. According to this view, the automation of jobs threatens not just routine tasks with rule-based activities but also, increasingly, jobs defined by pattern recognition and non-routine cognitive tasks.

It is this second camp – those who predict dramatic shifts in employment driven by technological progress – that a recent working paper by Carl Frey and Michael Osborne of Oxford University speaks to, and which has attracted a significant amount of attention. In it, they combine elements from the labour economics literature with techniques from machine learning to estimate how ‘computerisable’ different jobs are. The gist of their approach is to modify the theoretical model of Autor et al. (2003) by identifying three engineering bottlenecks that prevent the automation of given jobs – these are creative intelligence, social intelligence and perception and manipulation tasks. They then classify 702 occupations according to the degree to which these bottlenecks persist. These are bottlenecks which technological advances – including machine learning (ML), developments in artificial intelligence (AI) and mobile robotics (MR) – will find it hard to overcome.

Using these classifications, they estimate the probability (or risk) of computerisation – this means that the job is “potentially automatable over some unspecified number of years, perhaps a decade or two”. Their focus is on “estimating the share of employment that can potentially be substituted by computer capital, from a technological capabilities point of view, over some unspecified number of years.” If a job presents the above engineering bottlenecks strongly then technological advances will have little chance of replacing a human with a computer, whereas if the job involves little creative intelligence, social intelligence or perceptual tasks then there is a much higher probability of ML, AI and MR leading to its computerisation. These risks range from telemarketers (99% risk of computerisation) to recreational therapists (0.28% risk of computerisation).

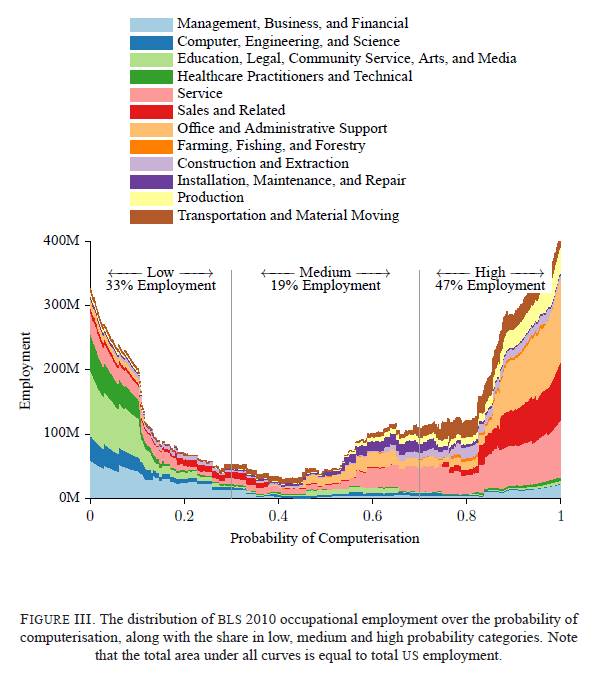

Predictions are fickle and so their results should only be interpreted in a broad, heuristic way (as they also say), but the findings are provocative. Their headline result is that 47% of US jobs are vulnerable to such computerisation (based on jobs currently existing), and their key graph is shown below, where they estimate the probability of computerisation across their 702 jobs mapped onto American sectoral employment data.

How do these risks distribute across different profiles of people? That is, do we witness a threat to high-skilled manufacturing labour as in the 19th century, a ‘hollowing out’ of routine middle-income jobs observed in large parts of the 20th as jobs spread to low-skill service industries, or something else? The authors expect that new advances in technology will primarily damage the low-skill, low-wage end of the labour market as tasks previously hard to computerise in the service sector become vulnerable to technological advance.

Although such predictions are no doubt fragile, the results are certainly suggestive. So what do these findings imply for Europe? Which countries are vulnerable? To answer this, we take their data and apply it to the EU.

At the end of their paper (p57-72) the authors provide a table of all the jobs they classify, that job’s probability of computerisation and the Standard Occupational Classification (SOC) code associated with the job. The computerisation risks we use are exactly the same as in their paper but we need to translate them to a different classification system to say anything about European employment. Since the SOC system is not generally used in Europe, for each of these jobs we translated the relevant SOC code into an International Standard Classification of Occupations (ISCO) code, which is the system used by the ILO. (see appendix) This enables us to apply the risks of computerisation Frey & Osborne generate to data on European employment.

Having obtained these risks of computerisation per ISCO job, we combine these with European employment data broken up according to ISCO-defined sectors. This was done using the ILO data which is based on the 2012 EU Labour Force Survey. From this, we generate an overall index of computerisation risk equivalent to the proportion of total employment likely to be challenged significantly by technological advances in the next decade or two across the entirety of EU-28.

It is worth mentioning a significant limitation of the original paper which the authors acknowledge – as individual tasks are made obsolete by technology, this frees up time for workers to perform other tasks and particular job definitions will shift accordingly. It is hard to predict how the jobs of 2014 will look in a decade or two and consequently it should be remembered that the estimates consider how many jobs as currently defined could be replaced by computers over this horizon.

Republishing and referencing

Bruegel considers itself a public good and takes no institutional standpoint. Anyone is free to republish and/or quote this post without prior consent. Please provide a full reference, clearly stating Bruegel and the relevant author as the source, and include a prominent hyperlink to the original post.