Blog Post

Blogs Review: Capital in the twenty-first century

Thomas Piketty, probably the leading researcher on inequality, has recently published his magnum opus “Capital in the twenty-first century”. The book, which is the culmination of years of research, paints a rather bleak picture of the future of capitalism.

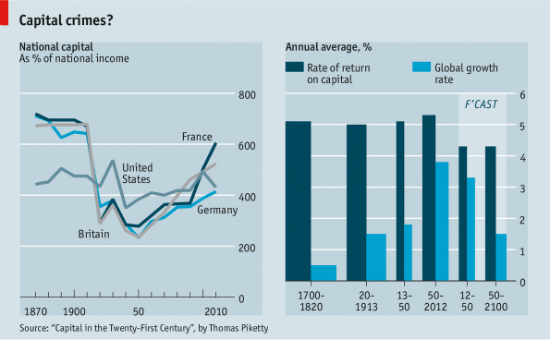

What’s at stake: Thomas Piketty, probably the leading researcher on inequality, has recently published his magnum opus “Capital in the twenty-first century”. The book, which is the culmination of years of research, paints a rather bleak picture of the future of capitalism: Analysing huge volumes of data, Piketty sides with Karl Marx rather than Simon Kuznets on the future of capitalism: Absent strong policy measures such as a global tax on capital returns, inequality will be ever-increasing. The economic community has welcomed this book, which aims to (re-)establish inequality as the most pressing economic issue of our time, as a monumental contribution with scores of reviews (twelve of them collected here by Brad deLong) and comments.

Ryan Avent summarizes Piketty’s key arguments in a series of posts on Free Exchange (see the discussion of the intellectual context of the book and of the key theories underlying the analysis as well as those of chapter 1, chapter 2, 3&4 – the remaining 12 chapters will be covered in the coming weeks). The middle of the 20th century was characterized by period of relative equity due to the economic and political effects of two World Wars and the Great Depression (destruction of capital, higher taxation and nationalisation of industries). Since the 1970s, however, income inequality is rising again and levels of wealth concentration are again approaching those of the pre-war era. The Kuznets-Curve idea that, as economies mature, they become more equal, is fallacious: What we witness now is a return to historic normality. The return of inequality is driven by the the soaring inequality in labour income, especially in the USA, and, most importantly, the return of wealth, the central topic of the book.

Daron Acemoglu (through Thomas B. Edsall) is not convinced that the data proves that we now return to the “natural tendency” of capitalist economies to generate inequality. The data is consistent with what Piketty says, but it is also consistent with certain technological changes and discontinuities (or globalization) having created a surge in inequality which will then stabilize or even reverse in the next several decades. It is also consistent with the dynamics of political power changing and this being a major contributor to the rise in inequality in advanced economies. We may be seeing parts of several different trends underpinned by several different major shocks rather than the mean-reverting dynamics following the shocks that Piketty singles out.

Branko Milanovic writes that Piketty dismisses Kuznets‘ inverted U curve for income inequality over an economy’s development on several grounds: First, he does not see any spontaneous forces in capitalism that would drive inequality of incomes down; rather, the only spontaneous forces will push concentration of incomes up. Second, he thinks that Kuznets misinterpreted a temporary slackening in inequality after World War II as a sign of a more benign nature of capitalism, while it was really due to the unique and unrepeatable circumstances. Third, he thinks that Kuznets’ theory owes its success in part to the optimistic message that it conveyed during the Cold War, namely that poorer capitalist economies were not forever condemned to high inequality. And finally, the data available to Kuznets in the 1950s was minimal and almost derisory.

Capital returns: the prime cause for divergence

Probably the most crucial dynamic in the book is the difference between the return rate on capital r and economic growth g. When r>g, wealth – which in Piketty’s analysis equals capital as anything other than labour that generates income – can grow faster than output and the capital income share keeps increasing.

Source: Free Exchange

Paul Krugman investigates how r-g can attain a positive value, thus allowing inequality to increase. In terms of the steady-state of a Solow growth model, in which the capital-output ratio is equal to the ratio of the savings rate over n (technological progress plus population growth), the impact of a reduction in n (reflecting decreasing global population growth and per capita growth rates) on r and g depends on the elasticity of substitution between capital and labor. If, as Piketty asserts, the elasticity of substitution is more than 1 (i.e. capital and labour are substitutes), the capital share rises, and r falls less than g. A growth slowdown would thus be causing inequality to increase. A question that remains open is how much of the decline in r relative to g in the 20th century reflected fast growth, and how much reflected policies that either taxed or in effect confiscated inherited wealth?

Edward Lambert thinks that Krugman leaves out one aspect in his last question: What about the impact of monetary policy? Loose monetary policy is also a policy that pushes up r relative to g. The rate of return on assets is increased when the cost of capital is lowered. Thus loose monetary policy is adding to the wealth inequality that is bringing down the US and other advanced economies. The US must protect its middle class. The solution is to raise the cost of capital through a combination of tightening monetary policy, raising taxes on capital & higher incomes and strengthening once again the transmission mechanisms of wealth to labor, namely unions, living wages and investing in locally owned businesses.

Branko Milanovic finds Piketty’s arguments why r may remain high interesting (for example, he sees today’s processes of expanding financial sophistication and international competition for capital as intended to help keep r high), but in arguing that the elasticity of substitution between capital and labour is likely to remain high, and that an increase in capital will not drive r down, he is running against one of the fundamentals of economic theory: decreasing returns to an abundant factor of production. Although Piketty is indeed critical of a blind belief that marginal returns always set the price for labour and capital, he does not develop these arguments.

Ryan Avent writes that sustained rates of return to capital above the rate of growth g may sound unrealistic – we would expect diminishing marginal returns to capital to cause r to reduce as capital is piled up. But Piketty shows that the rate of return on capital is remarkably constant over long periods, partly due to technology improvements. Innovation, and growth in output per person, creates investment opportunities even when shrinking populations reduce GDP growth to near zero. New technology can also make it easier to substitute machines for human workers, causing the capital share of income to rise. Amid a new burst of automation, wealth concentrations and inequality could reach unprecedented heights.

Drivers of convergence: growth and technology spread

Ryan Avent summarizes Piketty’s arguments on the inequality-lessening effect of growth: in the long run and under the right circumstances, the capital stock to GDP ratio should approach the ratio of the national savings rate to the national growth rate. This implies that rapid (absolute) economic growth is a force for economic convergence. It limits the relative importance of accumulated wealth. It comes in two components: population growth and per capita growth, both of which were roughly equally responsible for growth in the last 300 years. Population growth has peaked at 1.9% p.a. in the middle of last century and is now falling. And the rate of per capita growth also appears to be near what is likely to be a peak at above 2%, due to the present rapid catching-up of emerging markets. Taking these rates together, absolute growth has been around 4% p.a. in the past and may decline to 1.2% by the end of the century. This rate is more similar to the pre-industrial era of the past and will generate a longer shadow of accumulated wealth.

John Cassidy believes there is a chance that innovations may spur productivity growth, shifting it to a permanently higher rate and thus strengthening the forces of convergence. Also, he finds that Piketty pays slightly insufficient attention to decreasing inequality on a global scale, where millions of people have seen their lives improve in the recent pass. He also thinks Piketty doesn’t seriously consider the argument that globalization—and the rise of nations like China and India—is at once holding down wages and pushing up the profitability of capital, boosting inequality at both ends.

Ryan Avent writes that for Piketty, the principal force for convergence at present is the spread of new technologies from rich areas to poor ones. Countries that have been successful in the economic catch-up process have typically been economies that self-financed industrialisation on the back of high domestic savings rates. On the other hand, where a large share of capital is foreign-owned, it may create a strong incentive for governments to expropriate foreign capital, thus perpetuating institutional weakness. The gains from openness are therefore almost entirely down to the transfer of knowledge, rather than the efficiency benefits of free trade and capital flows. Avent finds this view excessively pessimistic: even if openness mostly entails foreign ownership and thus institutional weakness, cutting the poor off from goods markets has historically been a good way to keep them poorer than they need to be and to reinforce cronyist regimes.

Dean Baker does not share Piketty’s pessimism on profits exceeding growth rates: a very large share, perhaps a majority, of corporate profit hinges on rules and regulations that could in principle be altered. Examples are drug patents (allowing Indian low-cost generics to enter the market could severely limit the profits and value of corporate stock in that industry) or regulating the telecommunications sector, preventing monopolies and thus curtailing capital returns. And financial transaction taxes can be implemented, curtailing returns from financial capital. In the past, progressive change advanced by getting some segment of capitalists to side with progressives against retrograde sectors. In the current context this likely means getting large segments of the business community to beat up on financial capital.

Policy recommendation: A global tax on capital?

Thomas Piketty himself writes in the FT that many of the relatively egalitarian and inclusive institutions set up in Europe after World War II drew inspiration from the US. Very high, confiscatory tax rates for top incomes were an American invention of the inter-war years when the country was determined to avoid the disfiguring inequalities of class-ridden Europe. That experiment did not hurt the US. The main force driving inequality at present are, however, the strong returns to capital. What is required now, therefore, is a tax on vast fortunes, which is preferable over alternatives such as inflation (a soft expropriation of creditors to government) or a Russian approach to dealing with excessively ambitious oligarchs.

Branko Milanovic agrees that lowering r by implementing a global taxation of capital is key to limiting inequality. Sure, this may seem unrealistic, but ne would be wrong to dismiss the proposal out of hand. Nobody believes that it could be implemented hic et nunc, and neither does Piketty. It is based on several strong points: It is the most direct instrument attacking the key issue, capital returns. And capital taxes have a long history. Their technical requirements are not overwhelming: housing is already taxed; the market value of different financial instruments is easily ascertainable and the identities of owners known. The key problem is that capital taxation needs international coordination to eliminate the drawback of causing capital outflows from the countries implementing it. Although it will probably be impossible to bring all countries on board, a modest proposal built around the OECD countries or the US and EU seems feasible.

Lawrence Mishel (through Thomas B. Edsall) believes that the real problem is the suppression of wage growth, thus arguing that a strengthened labour movement is needed to counteract the development, rather than the capital tax proposed by Piketty.

Richard Freeman (also through Thomas B. Edsall) finds himself in full agreement with Piketty’s analysis – but has a different proposal: Let’s turn everyone into a capitalist. Much of labour inequality comes because high earners got paid through stock options and capital ownership. Therefore, “The way forward is to reform the structure of American business so that workers can supplement their wages with significant capital ownership stakes and meaningful capital income and profit shares.”

Republishing and referencing

Bruegel considers itself a public good and takes no institutional standpoint. Anyone is free to republish and/or quote this post without prior consent. Please provide a full reference, clearly stating Bruegel and the relevant author as the source, and include a prominent hyperlink to the original post.