Blog Post

Has the Chinese central bank really taken a hard line on liquidity?

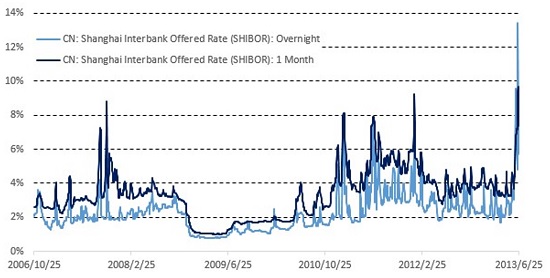

With the surge of the Shanghai Interbank Offered Rate (SHIBOR) since early June, China’s interbank market experienced a serious liquidity shortage last week. The overnight rate was 13.44 percent on 20 June compared to 2.95 percent on 20 May. The rate rise was triggered by several temporary shocks[i]. At the same time, bond yield rates have climbed and prices have declined. Tension in the financial market has increased, but the official response has been muted. How can China's central bank, the People's Bank of China (PBOC), be so calm in the face of the crisis?

With the surge of the Shanghai Interbank Offered Rate (SHIBOR) since early June, China’s interbank market experienced a serious liquidity shortage last week. The overnight rate was 13.44 percent on 20 June compared to 2.95 percent on 20 May. The rate rise was triggered by several temporary shocks[i]. At the same time, bond yield rates have climbed and prices have declined. Tension in the financial market has increased, but the official response has been muted. How can China’s central bank, the People’s Bank of China (PBOC), be so calm in the face of the crisis?

Figure 1: The interest rate in SHIBOR market

Source: SHIBOR.

The consensus among market participants is that banks have accumulated risky leverage and mismatched maturities through the shadow banking system. PBOC wants to teach banks a lesson in moral hazard. But has PBOC really taken a hard line? Central banks can take either a hard or a soft line. Passively injecting liquidity could alleviate the liquidity tension, but could result in increased moral hazard and, in turn, larger bailouts. For this reason, even authorities taking a soft line would be more reluctant to take steps in the first place.(Farhi and Tirole,2009)[ii]。

What signal has PBOC given? It warned the market ahead of the rate surge, then let the crisis happen, and even continued to take liquidity out of the system on 20 June.

Yet we can hardly conclude that PBOC is really taking a hard line. Even when the worst happens, according to Peng Wensheng, chief economist of China International Capital Corporation, Xiang Songzuo, chief economist of Agricultural Bank of China, and other observers, PBOC still has the situation under control. As noted in Forbes China[iii], it is a controllable crisis.

It is still uncertain if PBOC has shifted its stance from a soft to a hard line. This uncertainty perplexed investors until 25 June, five days after the liquidity crunch, when PBOC published an announcement to explain the situation and declare that liquidity had been provided to qualified banks.

To reduce the uncertainty, a regular mechanism should be established, so that the authorities can issue public communications in a proactive and timely way. It is better to increase clarity through much stronger signals sent by the authorities.

Of course, time inconsistency based on moral hazard always troubles monetary policy. Benassy-Quere et al (2010)[iv] suggest solutions: one is to limit the size of banks, so that none become too big to fail. This will make it easier for the authorities to take a hard line. Another solution is to ensure that risky investment is capped at a certain level.

But the case in China is more complicated, and strongly related to the characteristics of the economy:

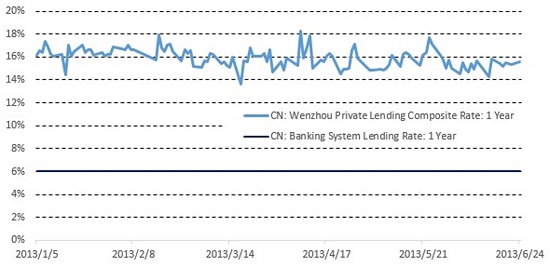

The official nominal interest rate is most likely lower than the equilibrium level[v]. The private lending rates in Wenzhou city (a pilot area for private financial services) are much higher than the official lending rates, even if one considers that private lending rates include a risk premium. Official banking sector lending carries an extremely low real interest rate because of inflation expectations, which fuel the asset bubble. These developments inevitably contribute to the maturity mismatch and high leverage.

Figure 2. The interest rates in China’s financial market: a dual-track system

Source: PBOC, Wenzhou Private Lending Registration Service Center.

Note: Wenzhou, a city in eastern China, is the pilot area for private financial services. The Wenzhou rate is expected to contribute to the creation of a private lending monitoring system[vi]. Since 21 June 2013, the private lending rates from a further three cities in western China have been included in the Wenzhou rate. It is the most important private lending rate in China. The private system credit mainly goes to small and medium-sized enterprises. On the other hand, the banking system lending rate published by PBOC is the benchmark rate for loans, which made up 56.3 percent of Total Social Financing[vii] in May 2013. In banking system, credit is dominated by state-owned enterprises or large companies.

Furthermore, inflation expectations encourage households to hold short-term assets, while China’s huge infrastructure investment demands long-term debt.

Therefore, China still has a long way to go to disassemble the liquidity crisis bomb.

Xu Qiyuan

[i] PBOC explained this on 25 June: Liquidity has been “affected by various factors such as rapid loan growth, payment of annual corporate income tax before deadline, cash demand during the Dragon Boat Festival holiday, changes on foreign exchange market, payment of required reserves, and etc,” So “interest rates have recently moved up and fluctuated on money market”. Source:http://www.pbc.gov.cn/publish/english/955/2013/20130626170224340616466/20130626170224340616466_.html

[ii] Emmanuel Farhi, Jean Tirole, Collective Moral Hazard, Maturity Mismatch And Systemic Bailouts, NBBR Working paper series 15138, 2009.

[iii] http://www.forbeschina.com/review/201306/0026550.shtml?utm_source=zaker&utm_medium=app&utm_campaign=news

[iv] Agnes Benassy-Quere, Benoit Coeure, Pierre Jacquet, and Jean Pisani-Ferry, Economy Policy: Theory and Practice, OXFORD Universoty Press, 2010. pp. 305-306.

[v] He and Wang (2012) point out an additional aspect of the Chinese banking sector: On the supply side, because of the low deposit rate ceiling, competitive considerations induce banks to push out loans as long as the marginal cost of loans is lower than the lending rate. On the demand side, firms have excess demand for loans because the loan rate is lower than the equilibrium rate. Thus, without a lending-rate floor, the loan market would be cleared at a lower lending rate and a much larger amount of loans, which would result in an excess of credit in the economy. Cited from: Dong He, Honglin Wang, Dual-track interest rates and the conduct of monetary policy in China,China Economic Review, Volume 23, Issue 4, December 2012, Pages 928–947.

[vi] http://hangzhou.pbc.gov.cn/publish/hangzhou/1250/2012/20121204163706022241340/20121204163706022241340_.html#

[vii] http://www.pbc.gov.cn/publish/html/kuangjia.htm?id=2013s18.htm

Republishing and referencing

Bruegel considers itself a public good and takes no institutional standpoint. Anyone is free to republish and/or quote this post without prior consent. Please provide a full reference, clearly stating Bruegel and the relevant author as the source, and include a prominent hyperlink to the original post.