Blog Post

Blogs review: The Monetary Regime and the drawbacks of NGDP targeting

What’s at stake: There has been much ink spilt (except maybe in the eurozone) over the last few years about the need to move away or at least complement the flexible inflation-targeting framework so that central banks can create expectations of future expansionary policy in a liquidity trap without changing its long-run goals. One idea – Nominal GDP targeting – has gathered most attention. After qualifying the idea as “powerful” and raising expectations of a possible future adoption, the Bank of England governor-designate Mark Carney reversed course and said that he was “far from convinced” by the idea in front of the Treasury select committee yesterday. While he didn’t lay out precisely the intellectual reasons for that change of heart, we’ve tried to put together some of the reasons put forward against NGDP targeting.

What’s at stake: There has been much ink spilt (except maybe in the eurozone) over the last few years about the need to move away or at least complement the flexible inflation-targeting framework so that central banks can create expectations of future expansionary policy in a liquidity trap without changing its long-run goals. One idea – Nominal GDP targeting – has gathered most attention. After qualifying the idea as “powerful” and raising expectations of a possible future adoption, the Bank of England governor-designate Mark Carney reversed course and said that he was “far from convinced” by the idea in front of the Treasury select committee yesterday. While he didn’t lay out precisely the intellectual reasons for that change of heart, we’ve tried to put together some of the reasons put forward against NGDP targeting.

The case to reset basis of monetary policy

Martin Wolf writes that proponents of the current regime of flexible inflation targeting justified it not only on the proposition that it would stabilize inflation, but that it would help stabilize the economy. It failed to do so. With the economy in the doldrums and the arrival of Mark Carney as governor of the Bank of England in July, this is the ideal time for a rigorous, comprehensive and open debate.

Simon Wren-Lewis writes that the Bank of England has interpreted this flexibility as trying to hit the inflation target in two years time. The general view was that over this kind of time frame, hitting the inflation target would be consistent with closing the output gap. So although minimizing the output gap was not a primary policy objective, that objective would be fulfilled under flexible inflation targeting. The theory behind this view is that inflation is ultimately determined by a Phillips curve, which implies inflation will only be stable in the long run if the output gap is zero. The MPC has currently set policy to achieve the inflation target in two years time, but it does not expect the output gap to come near to being closed in two years time. So the inflation objective is overriding the output gap objective.

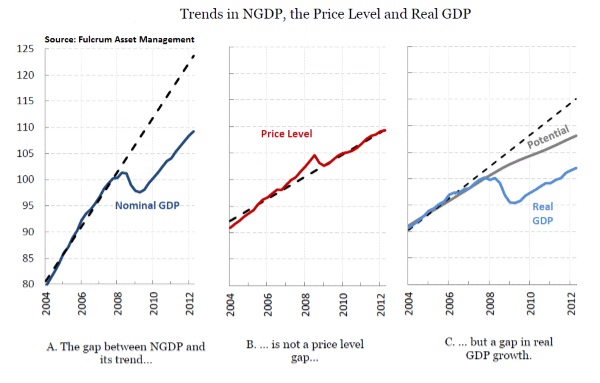

The need for history dependent targets

David Romer in the January 2013 update of his online undergraduate textbook writes that, qualitatively, targeting a nominal GDP path is similar to targeting a price-level path: it provides a framework through which the central bank can create expectations of future expansionary policy in a liquidity trap without changing its long-run goals. But although targeting a price-level path has desirable qualitative properties, its quantitative effects may be small. Five years after the U.S. economy entered into a recession in late 2007, for example, the price level was only a few percent lower than it would have been if it had continued to grow by 2 percent per year (see the debate between Dave Altig and Mike Bryan and Andy Harless for more on this). Thus the amount of additional expected inflation created by targeting a price-level path would have been small. Nominal GDP, on the other hand, fell almost 10 percent below its pre-recession path in the five years after the 2007 business cycle peak.

Source: Gavyn Davies

In a recent speech, Mark Carney had raised expectation of a change in monetary regime when he said that a NGDP target “could in many ways be more powerful than employing thresholds under flexible inflation targeting”. By adding history dependence to rate setting, “bygones are nor bygones”.

Implementation drawbacks: revisions in NGDP and output gap estimates

In contrast with flexible inflation targeting, NGDP targeting is both a target and a rule, which creates new issues of implementation for central bankers used to the dissociation between a Taylor rule and an inflation target.

As recently highlighted by Charles Goodhart and coauthors, one of the main problems of NGDP targeting is that NGDP data are only available quarterly, with a lag, and are subject to substantial revisions overtime. The FRED website offers an opportunity to compare vintage (real time) data and revised data. For the UK, the comparison has been done by Richard Jeffrey and shows substantial revisions. The question remains open as to the way central banks would deal with such revisions, especially to the extent that the effect of these revisions might be more important for the public since they are directly related to the target.

On the other hand proponents of NGDP targeting, such as McCallum, have argued Taylor rules are harder to implement because of the need to estimate an output gap. And as pointed by Athanasios Orphanides, real time data on output gap have been very unreliable and, at least, in part responsible for monetary policy mistakes of the Fed in the 1970s. For McCallum the central bank can, under NGDP targeting, manage nominal spending in a manner that does not involve conceptually the Phillips curve. It can conduct policy without use of that elusive relationship. By contrast, if it focuses on inflation and real GDP separately, or on inflation alone, it cannot possibly avoid its use. Scott Sumner writes that unlike the Taylor Rule, under NGDP targeting policymakers only face the issue of estimating the natural level of output at the point of adoption. In contrast, alternative policies such as flexible inflation targeting force policymakers to estimate output gaps each and every time they make a decision.

In a 2002 paper, Glenn Rudebusch integrated this problem in a New Keynesian model and concluded that this problem was not enough to give an advantage to GNP targeting over Taylor rule.

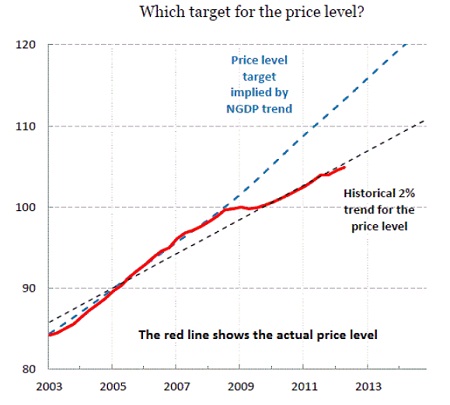

Implementation drawbacks: the sensitivity to starting points

Charles Goodhart and Morgan Stanley economists Melanie Baker and Jonathan Ashworth write that the start date and growth path in an NGDP targeting framework are crucial, yet the answer to the question when to start history is essentially arbitrary and any overestimation of the sustainable growth rate of GDP would bring about a significantly higher rate of inflation, particularly as advocates generally seem to propose quite high growth rates inconsistent with conservative assumptions about potential growth and a target inflation of 2%. If we knew what the future sustainable long-run rate of growth would be, we could set a current nominal GDP growth target that would on average deliver that, plus 2% inflation. But we do not.

Scott Sumner writes that this is indeed a difficult question. There is no magic formula for deciding where to start a NGDP trajectory. In principle you’d aim for a near term target that created the most stable macroeconomic environment. That’s not very difficult if the economy already seems to be close to its long run equilibrium, or “natural rate of output.” If you’ve recently departed from equilibrium, then the principle of “level targeting” would call for policymakers to bring NGDP back to the previous long-term trend line. That’s because all sorts of (nominal) labor and debt contracts were probably made under expectations that NGDP would continue growing at trend. The most difficult problem is when you’ve departed from the previous trend line for an extended period of time, and where it’s difficult to estimate the natural rate of output. In this case, it should be based on a combination of the trend line before and after the shock reflecting the fact that current wage and debt contracts partly reflect pre-2008 expectations and partly reflect post-2008 expectations.

The risk of excess inflation

Gavyn Davies writes that if such a target were pursued, we might expect the initial consequence to be a rise in real GDP back to its potential path, with no change in inflation relative to the 2 per cent path built into expectations and (implicitly) into the NGDP target. So far, so good. However, if the Fed then maintained its commitment to NGDP all the way to the target path, it would also push real GDP above potential, and therefore create excess inflation. In fact, the price level would embark on an entirely new and higher path than anything the Fed (or, possibly, Professor Woodford) has been ready to contemplate. The graph on the left shows what would happen to the price level path if the Fed insisted on hitting its NGDP target, assuming that the CBO is right about potential GDP.

Source: Gavyn Davies

David Beckworth points to this paragraph in Woodford’s Jackson Hole speech for an answer to that concern: “Such a commitment would accordingly require pursuit of nominal GDP growth well above the intended long-run trend rate for a few years in order to close this gap. At the same time, such a commitment would clearly bound the amount of excess nominal income growth that would be allowed, at a level consistent with the Fed’s announced long-runt target for inflation.”

Uncertainty about future inflation

Charles Goodhart and Morgan Stanley economists Melanie Baker and Jonathan Ashworth write that given our uncertainty about sustainable growth, an NGDP target also has the obvious disadvantage that future certainty about inflation becomes much less than under an inflation (or price level) target. In order to estimate medium- and longer-term inflation rates, one has first to take some view about the likely sustainable trends in future real output. The latter is very difficult to do at the best of times, and the present is not the best of times. So shifting from an inflation to a nominal GDP growth target is likely to have the effect of raising uncertainty about future inflation and weakening the anchoring effect on expectations of the inflation target.

History of ideas

We were about to correct a previous mistake from an earlier blogs review – where one of us wrote that the debate dated back to the 1990s – by writing that the debate on nominal GDP targeting actually goes back to the 1970s, was then called nominal income targeting, and that it included James Meade, James Tobin, Robert Hall and Robert McCallum as early proponents of that approach. But even this is wrong according to Scott Sumner who writes that the idea is actually older than that as a number of interwar economists, including Hayek, advocated NGDP targeting. People (us included apparently!) should read George Selgin’s work on the history of NGDP targeting.

In the 1970s and 1980s, including in McCallum work (and the so-called McCallum rule), nominal GDP targeting and money targeting were close concepts and often went together. In his recent book, “Making the monetary union” (p.126), Harold James mentions some early discussions on this concept at the ECOFIN back in 1972. Stephen Williamson writes that McCallum looked at the equation of exchange and thought: The central bank controls M, but if M is growing at a constant rate and V is highly variable, then PY is bouncing all over the place. Why not make PY grow at a constant rate, and have the central bank move M to absorb the fluctuations in V? As economists we can disagree about how growth in nominal income will be split between growth in P and growth in Y, depending in part on our views about the sources and extent of non-neutralities of money. But, McCallum reasoned, NGDP targeting seems agnostic.

Republishing and referencing

Bruegel considers itself a public good and takes no institutional standpoint. Anyone is free to republish and/or quote this post without prior consent. Please provide a full reference, clearly stating Bruegel and the relevant author as the source, and include a prominent hyperlink to the original post.